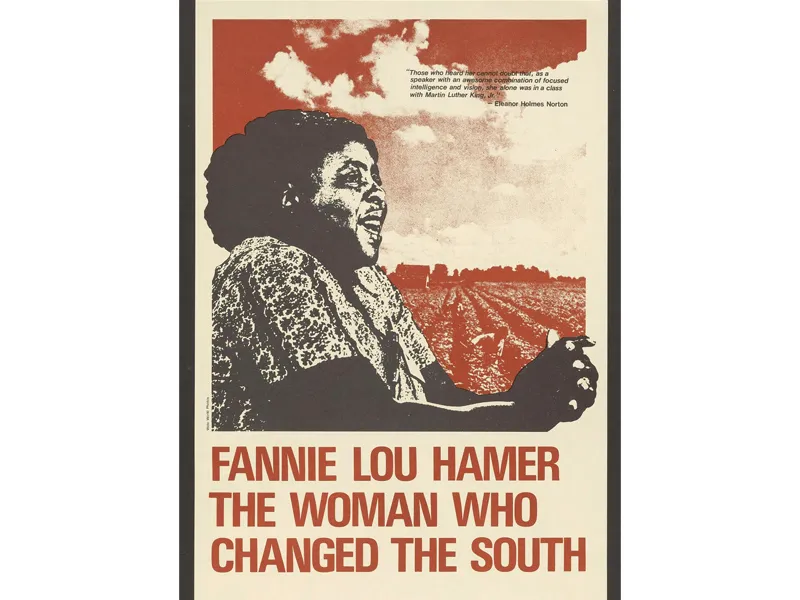

Fannie Lou Hamer’s Dauntless Fight for Black Americans’ Right to Vote

The activist did not learn about her right to vote until she was 44, but once she did, she vigorously fought for black voting rights

:focal(2206x851:2207x852)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/2c/892c62a7-3942-4b52-9059-10da8442a98c/gettyimages-515450184.jpg)

Like many African Americans living in the Jim Crow South, Fannie Lou Hamer was not aware she had voting rights. “I had never heard, until 1962, that black people could register and vote,” she once explained. The granddaughter of enslaved black people, Hamer was born in Montgomery County, Mississippi, in 1917. As the youngest of 20 children in a family of sharecroppers, she was forced to leave school during the sixth grade to help on the plantation. In 1925, when Hamer was only 8, she witnessed the lynching of a local sharecropper named Joe Pullam who had dared to speak up for himself when local whites refused to pay him for his work. “I remember that until this day, and I won't forget it,” she admitted in a 1965 interview. By that point, Hamer had become a nationally recognized civil rights activist, boldly advocating for the right to political participation that black Americans had long been denied.

Pullam’s lynching revealed the stringent conditions of the Jim Crow South. Black Americans were expected to be subordinate to whites, hardly valued for their labor and certainly not their intellect. On a daily basis, white Southerners told black Americans where to live, where to work and how to act. Transgressions could result in devastating consequences.

White Southerners also completely shut black people out of the formal political process. In the wake of the Civil War, the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments confirmed that formerly enslaved people were citizens and enfranchised black men. During the Reconstruction era, black men made use of this right, voting and running for public office; black women were not afforded that right. Upon the dissolution of Reconstruction, white Southerners used an array of legal and extralegal measures—including poll taxes, grandfather clauses and mob violence—to make it nearly impossible for African American men to vote.

When the 19th Amendment extended the vote to women in 1920, these voter suppression tactics meant that the rights black suffragists had fought for were inaccessible in practice. By the 1960s, only 5 percent of Mississippi’s 450,000 black residents were registered to vote.

In 1962, Hamer attended a meeting arranged by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an interracial civil rights group that played a central role in organizing and encouraging black residents in the South to register to vote. “They were talking about [how] we could vote out people that we didn’t want in office,” she recalled. “That sounded interesting enough to me that I wanted to try it.” What Hamer came to realize in that moment was her ability to transform American society. Despite humble beginnings and a limited formal education, access to the ballot meant that she would be empowered to shape local, state and national politics.

That year, at the age of 44, Hamer joined SNCC and vowed to try to register to vote.

In August, she traveled by a rented bus with 17 other civil rights activists from her hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi, to Indianola, approximately 26 miles away, to get her name on the voter rolls. Hamer and her colleagues anticipated encountering roadblocks on their trip; they knew the dangers of defying white supremacy.

After making it through the courthouse door, they were informed that they had to pass literacy tests in order to register to vote. The test involved reading and interpreting a section of the state constitution. Hamer did the best she could and left, nervously watching the armed police officers who had surrounded their bus. While she managed to leave without incident, she and her colleagues were later stopped by the police and fined for driving a bus that was supposedly “too yellow.”

When Hamer arrived home later that evening, the white owner of the plantation on which she and her husband, Perry, worked as sharecroppers confronted her. He gave her an ultimatum, Hamer recalled: “If you don’t go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave.” Her boss added, “We are not ready for that in Mississippi.”

Hamer left that evening and never returned, leaving her family behind temporarily after the landowner threatened to keep their possessions if Perry did not finish helping with the harvest. Several days later, white supremacists sprayed 16 bullets into the home where Hamer was staying. Hamer knew the bullets, which had hurt no one, had been meant for her, yet she was undeterred. “The only thing they could do to me was to kill me,” she later said in an oral history, “and it seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time ever since I could remember.”

Nearly a year later, in June 1963, Hamer—now a SNCC field secretary, speaking about voting rights in dozens of cities across the country—was traveling back home with fellow activists to Mississippi after attending a voter’s workshop in South Carolina. They decided to stop in Winona, Mississippi, to grab a bite to eat. What was supposed to be a quick rest stop became one of the most harrowing experiences of Hamer’s life.

First, the owners of the restaurant refused to serve black patrons. Then, from the bus, Hamer noticed police officers shoving her friends into their patrol cars. Within minutes, an officer grabbed Hamer and violently kicked her.

The beating only intensified when Hamer and other members of the group arrived at the Winona jailhouse, where the police’s line of questioning focused on the workshop they had attended. They prodded for information about SNCC’s voter-registration project in Greenwood, Mississippi. The officers were incensed—offended even—at the very idea that Hamer and her colleagues would defy segregation laws at the restaurant and play an active role in bolstering the political rights of black people in Mississippi.

The beating Hamer endured over four days in Winona left her physically disabled and with permanent scars. As she later explained, “They beat me till my body was hard, till I couldn’t bend my fingers or get up when they told me to. That’s how I got this blood clot in my left eye—the sight’s nearly gone now. And my kidney was injured from the blows they gave me in the back.”

Hamer could not be thrown off her mission. She recounted her experience in Winona on numerous occasions—most notably at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. At the time, the Democratic Party dominated Southern politics. Hamer showed up at the convention as a representative of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), an organization she had helped establish to challenge the segregated, all-white Mississippi delegation at the DNC. As Hamer and her colleagues pointed out, a “whites-only” Democratic Party representing a state in which one out of five residents were black undermined the very notion of representative democracy. In their eyes, those who supported a “whites-only” party were no different than white mobs who employed extralegal methods to block African Americans from voting.

In her televised DNC speech, Hamer called out American hypocrisy. “Is this America,” she asked, as tears welled up in her eyes, “the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Hamer had pulled back the curtain. The United States could not claim to be a democracy while withholding voting rights from millions of its citizens. Although the MFDP delegation did not secure its intended seats at the convention, Hamer’s passionate speech set in motion a series of events that led to the 1965 passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act (VRA). Her address, combined with the nationwide protests led by black activists, compelled President Lyndon B. Johnson—who had interrupted Hamer’s speech with a press conference of his own—to introduce federal legislation that banned local laws, like literacy tests, that blocked African Americans from the ballot box. The act also put in place (recently curtailed) restrictions on how certain states could implement new election laws new election laws.

The VRA significantly bolstered black political participation in the South. In Mississippi alone, the number of African Americans registered to vote dramatically increased from 28,000 to approximately 280,000 following its passage. In the aftermath of the VRA, the number of black elected officials in the South more than doubled—from 72 to 159—following the 1966 elections.

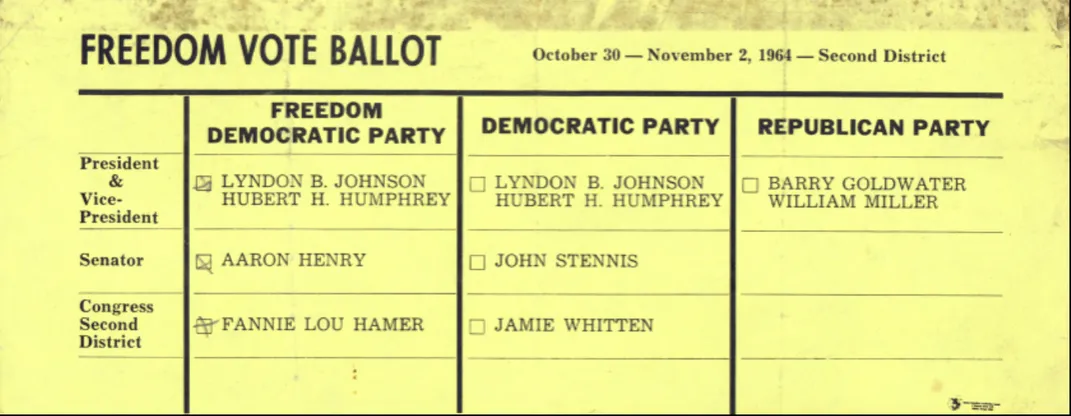

Hamer not only helped to register voters but empowered others by entering the realm of electoral politics herself. In 1964, one year after she succeeded in registering herself to vote for the first time, Hamer ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives to challenge white Mississippi Democrat Jamie Whitten, who was seeking a 13th term. Although her chances of winning were slim, she explained to a reporter, “I’m showing people that a Negro can run for office.” Despite a limited budget, Hamer ran a spirited campaign backed by a coalition of civil rights organizations, promising to tackle the issues of poverty and hunger. The Democratic Party refused to allow Hamer’s name on the official ballot, but the MFDP organized mock election events and brought black Mississippi voters out in record numbers. An estimated 60,000 African Americans participated and cast a symbolic vote for Hamer in what the MFDP termed a “Freedom Ballot.”

Unsuccessful in her first bid for Congress, Hamer went on to run for office twice more. In 1967, her second attempt was disqualified by election officials, and four years later, she yet again encountered defeat, this time vying for a state senate seat. Her motivation, she explained in a 1971 speech, was that “We plan to bring some changes in the South. And as we bring changes in the South, the northern white politician won’t have any excuse and nowhere to hide.”

In the latter years of her life, Hamer remained at the forefront of the fight for black political rights. She established Freedom Farms, a community-based rural and economic development project, in 1969. While the initiative was a direct response to the high rates of poverty and hunger in the Mississippi Delta, Freedom Farms was also a means of political empowerment. “Where a couple of years ago, white people were shooting at Negroes trying to register,” she explained in 1968, “now they say, ‘go ahead and register—then you’ll starve.’” In the late 1960s and 1970s, she called out white Southerners who threatened to evict sharecroppers who registered to vote. And as a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus, which still promotes women politicians today, Hamer worked to expand women’s political participation during the 1970s.

For Hamer, who died in 1977, all of these efforts were grounded in the recognition that the act of casting a ballot was a fundamental right of every American citizen. She had grasped its power and was determined never to let it go.