Daughters of Wealth, Sisters in Revolt

Gore-Booth sisters, Constance and Eva, forsook their places amid Ireland’s Protestant gentry to fight for the rights of the disenfranchised and the poor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120710084038constance-gore-booth-small.jpg)

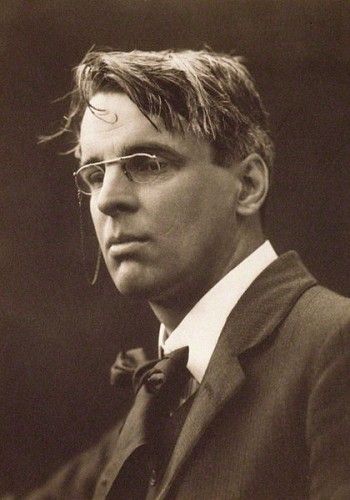

At the end of the 19thcentury, William Butler Yeats was a given a bedroom at Lissadell House, the majestic estate of Sir Henry Gore-Booth on the shores of Drumcliff Bay, not far from Yeats’ birthplace in Sligo County. For two years, Yeats stayed in the house amid the enchanted landscape of Ireland’s West Coast, the guest of a “very pleasant, kindly, inflammable family.” But it was clear that Yeats, who was entering his 30s, was also enchanted by the beauty of the Gore-Booth sisters, Constance and Eva. Decades later he would write:

The light of evening, Lissadell,

Great windows open to the south,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

In 1887, Constance and Eva Gore-Booth were presented at the court of Queen Victoria, with Constance, 19 at the time and older than Eva by two years, described by some in Victorian England as “the new Irish beauty.” Moving in the aristocratic circle of the Protestant Ascendancy, under which Ireland was dominated politically and economically by great landowners like their father, the Gore-Booth sisters were seemingly destined to live lives replete with the comforts and privileges of the landed class. But both women eventually broke from their background, rejected their wealth and dedicated their lives to confrontation and the cause of the poor.

Less than two decades after she sat at Lissadell for a portrait by Yeats, Constance would be sitting in a Dublin jail cell, listening to the volleys of firing squads as she awaited her own execution for her involvement in the Easter Rising. And Eva, the “gazelle” in Yeats’ poem, would become an acclaimed poet herself, as well as a prominent voice for women’s suffrage and the leading figure in an attempt to get her sister a reprieve.

Born in London in 1868 but raised in the Irish wilderness, Constance Gore-Booth had captured the attentions of Yeats, her Sligo neighbor, at a young age. Something of a timid horseman himself, Yeats “respected and admired” the girl who was on her way to becoming known as one of the best horsewomen in all of Ireland—unmatched, it was said, at riding to hounds. She was, according to Yeats, often in trouble around the estate for “some tomboyish feat or reckless riding.”

The sisters also gained a deep appreciation for art while living at Lissadell. The noted Irish portraitist Sarah Purser, also a guest, was inspired to do an iconic painting of the Gore-Booth girls in the woods around the estate. While Constance took after her father, Sir Henry Gore-Booth, an Arctic explorer and avid hunter in Africa, both girls clearly reflected another facet of his character. Sir Henry was reported to have suspended the collection of rents and made sure his tenants had food during 1879-80 famine, and his daughters were brought up with genuine concern for the poor.

Neither Constance nor Eva was interested in marrying within their class. Instead, Constance traveled to London in 1892 to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, then to Paris, where she continued to paint and study at Académie Julian. She claimed she was “married to art” and wore a ring to show it, smoked cigarettes, made a range of friends and earned the nickname “Velo” for riding her bicycle to the studio each day. When a Parisian girl teased about her about her funny-sounding English, Constance marched her to a faucet and held her head under running water.

By 1893, the Gore-Booth sisters had begun to occupy themselves with the cause of women’s suffrage—stirrings that did not sit well with Sir Henry and Lady Gore-Booth. Constance became the president of a suffrage committee and made a rousing speech in Drumcliff, noting that the number of women who signed petitions had been dramatically increasing over recent years. One man heckled, “If my wife went to vote she might never come back!”

“She must think very little of you, then,” Constance shot back to a crowd cheering in delight.

Eva became an accomplished poet and one of Yeats’ circle, and fell in love with the English suffragist and pacifist Esther Roper. The two women would spend the rest of their lives together, working on social issues ranging from workers’ rights to capital punishment.

Constance, too, would pursue a political life. Back in Paris, after her family had given up on the prospects of her ever marrying, she met Count Casimir Markievicz, a Polish artist from a wealthy family. They married and had a daughter, Maeve, in 1901, but they left her at Lissadell to be raised by her grandparents while they moved to Dublin to pursue their art.

By 1908, Constance had turned to the movement for Irish independence from British rule. She joined Sinn Fein, the Irish republican party, as well as the Daughters of Ireland—a revolutionary women’s movement—and teamed up with Eva to oppose the election of Winston Churchill to the British parliament. As the nationalist cause gained momentum, Constance founded the Warriors of Ireland (Fianna Éireann), which trained teenagers in the use of firearms. Speaking at a rally of 30,000 people opposed to King George V’s visit to Ireland in 1911, Countess Constance experienced her first arrest, after she helped stone the likeness of the King and Queen and tried to burn the British flag.

She took out loans and sold her jewelry to feed the poor and started a soup kitchen for children, around the same time she joined the Irish Citizen Army, led by James Connolly, the socialist and Irish republican leader. In 1913, her husband left Ireland to live in Ukraine—separate from Constance but not estranged, as the two would correspond for the remainder of her life.

In April 1916, Irish republicans staged an insurrection; Constance was appointed staff lieutenant, second in command at St. Stephen’s Green, the park in central Dublin. With her troops responsible for barricading the park, fighting flared after Connolly shot a policeman who had tried to prevent him from entering City Hall. Rumor had Constance shooting a British army sniper in the head, but she was never charged in such a death. Pinned down by British fire at St. Stephen’s Green, she pulled her troops back to the Royal College of Surgeons, where they held out for nearly a week before surrendering.

Taken to Kilmainham jail, Constance Markievicz was isolated from her comrades and court-martialed for “causing disaffection among the civilian population of His Majesty”; she was convicted and sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to life in prison because of her sex.

A few days later, she heard a volley from a firing squad at dawn and was informed that her mentor, James Connolly, had been executed.

“Why don’t they let me die with my friends?” she asked.

Transferred to a prison in England, she was sentenced to hard labor and fed limited rations. Eva Gore-Booth, a highly skilled activist, saw her sister’s failing health, lobbied for more humane treatment of prisoners, and in 1917 helped to get her sister included in an amnesty for participants in the Easter Rising.

Constance returned to Ireland a hero and was practically carried by a welcoming crowd to Liberty Hall in Dublin, where she declared herself back in politics. As Sinn Fein’s new leader, Eamon de Valera saw Constance Markievicz elected to the 24-member executive council. But in 1918, she was back in jail after the British arrested Sinn Fein’s leaders for working against the conscription of troops for World War I, yet she managed, from prison, to become the first woman elected to the British House of Commons.

Then she announced that she would refuse to take her seat, in accordance with Sinn Fein’s abstentionist policy. After all, she declared, she was “imprisoned by the foreign enemy.” She was then elected to the Dáil Éireann, the parliament established by unilateral declaration in the drive for Irish independence. After the drive secured freedom for 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties, she was re-elected to the Dáil—but then jailed in 1923, during the Irish Civil War, which was fought over the degree of independence Ireland had achieved. In prison Constance organized a hunger strike with nearly 100 female prisoners and was released a month later.

Constance remained in touch with Eva and even managed to reunite with Casimir in London. He was said to have been shocked by the sight on his bride, now in her mid-50s, gaunt from the hardships of incarceration. Eva, frail from cancer, died in June of 1926. Constance, heartbroken, did not attend the funeral. “I simply cannot face the family,” she said.

Re-elected in the Irish General Election along with de Valera in June of 1927, Constance, too, was quite ill, possibly with tuberculosis. She was hospitalized the next month in a public ward in Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital. Casimir arrived, with roses, for a deathbed visit that Constance would describe as the happiest day of her life. She’d been long estranged from her daughter, and there would be no reunion before Constance died, on July 15.

De Valera spoke at her funeral and carried her coffin; thousands lined the streets to see the procession. And though she is remembered fondly in Ireland, both politically and with a bust at St. Stephen’s Green, the words of her old friend Yeats were less than kind. In “In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markievicz,” the poet famously observed, “The innocent and the beautiful/have no enemy but time” and continued:

The older is condemned to death,

Pardoned, drags out lonely years

Conspiring among the ignorant.

I know not what the younger dreams—

Some vague Utopia—and she seems,

When withered old and skeleton-gaunt,

An image of such politics.

Sources

Books: Anne M. Haverty, Constance Markievicz: Irish Revolutionary, New York University Press, 1988. Marian Broderick, Wild Irish Women: Extraordinary Lives From History, University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Articles: Constance Marcievicz (nee Gore-Booth) and the Easter Rising, Sligo Heritage, http://www.sligoheritage.com/archmark2.htm

Lissadell House and Gardens, Sligo, Ireland, Lissadel Online, http://www.lissadellhouse.com/index.html A St. Pat’s Toast: The Rebel Countess, by Aphra Behn, Daily Kos, March 17, 2007, http://www.dailykos.com/story/2007/03/17/312918/-A-St-Pat-s-Toast-The-Rebel-Countess#comments Constance Georgine Gore Booth, Countess Markievicz, The Lissadell Estate, http://www.constancemarkievicz.ie/home.php Constance Markievicz: The Countess of Irish Freedom, The Wild Geese Today, http://www.thewildgeese.com/pages/ireland.html#Part1

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)