Constance Baker Motley Taught the Nation How to Win Justice

The pathbreaking lawyer and “Civil Rights Queen” was the first Black woman to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court

:focal(600x451:601x452)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ad/19/ad195668-90c6-4059-b7cd-314011983d07/opener.jpg)

In the spring of 1963, Constance Baker Motley watched the protests in Birmingham, Alabama, with hope—and concern. The nation’s most segregated city, Birmingham had become the center of the struggle for Black equality. Previous demonstrations there led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom she considered “an American hero,” had produced “no results,” Motley wrote in her memoir. Consequently, King and other leaders began planning more dramatic action, including the Children’s Crusade. “Civil disobedience was not working; massive resistance was,” she wrote. Indeed, the zeal of the protesters in April and May of that year led to a climactic legal battle. Motley’s heroic role in it would help lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as public outrage over the violent white response to peaceful protests spurred Congress to action.

The pathbreaking protégée of Thurgood Marshall, Motley had spent many years as the only woman lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF). She had written the original complaint in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which helped desegregate public schools, and would later help integrate flagship public universities in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Now, King—whom she had rescued the previous year from a dank, dangerous jail cell after he was arrested during a protest in Albany, Georgia—again reached out to the LDF in hopes of saving the campaign in Birmingham, which was faltering under abuse from local law enforcement. “It was a desperate plea,” Motley recalled./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/54/4554bbd3-19a4-46e0-b481-9576263e448b/4.jpg)

On April 3, 1963, King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), alongside local activists, launched the five-week-long Project C—the “C” standing for nonviolent “confrontation.” The courts posed an immediate threat: Local judge W.A. Jenkins had prohibited a protest planned for Good Friday, April 12. Out of respect for the Brown decision, King had vowed never to violate a federal court order. But he felt no such obligation toward bigoted state and local judges. “Injunction or no injunction,” he said at a press conference, “we are going to march.” King, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and the Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy defied the court order, marching with around 50 protesters from the Zion Hill Baptist Church into the city.

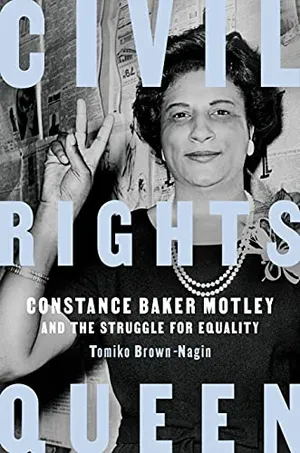

Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality

The first major biography of one of our most influential judges—an activist lawyer who became the first Black woman appointed to the federal judiciary—that provides an eye-opening account of the twin struggles for gender equality and civil rights in the 20th century.

King was jailed for contempt of court after the Good Friday march, spending eight days behind bars, where he composed his well-known manifesto “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” King knew he would need the right lawyer to beat back the greater legal challenges to come. Enter Motley, known as the “Civil Rights Queen” for her courtroom feats.

Released from jail on a $300 bond, King faced trial for contempt of court. Motley, joined by three male lawyers, served as his defense counsel. Her reputation drew a crowd: On April 23, the Jefferson County Courthouse teemed with spectators. Black Alabamians had come from all over to see the Columbia University-trained woman lawyer who famously “took no prisoners,” recalls Clarence Jones, a close adviser to King. Courthouse employees—nearly all white women—piled into court to watch Motley challenge segregationists with her signature tenacity. When a dismissive prosecutor pointed a finger at Motley and called her “she” instead of “Mrs. Motley,” the lawyer responded: “If you can’t address me as ‘Mrs. Motley,’ don’t address me at all.”

Unhappily for King, the judge presiding over the trial, W.A. Jenkins, was the same judge who had initially prohibited the demonstration. In her opening argument, Motley spoke in her characteristic low, steady voice. “There is not a shred of evidence,” she insisted, “that these defendants engaged in unlawful activity of any kind.” Regardless of the court order blocking the demonstration, protesters could not legally be punished, and Black protesters could not be singled out for exercising constitutionally protected rights to assemble. Under Motley’s cross-examination, W.J. Haley, chief inspector of the Birmingham Police Department, admitted the city had targeted movement leaders and acknowledged the mass arrests were the first time in 20 years the city had enforced the law against parading without a permit. Still, Jenkins found the leaders guilty and sentenced each to five days in jail. Motley appealed—to no avail.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/3f/b13f521f-eb5c-4eaa-bb2f-5272b179c764/3.jpg)

Indeed, the movement sputtered even after the ministers’ release from jail, until King, on the advice of SCLC comrade the Rev. James Bevel, had Project C begin recruiting schoolchildren for demonstrations. Hundreds of youngsters, including prom queens, athletes and academic standouts, joined the protests. On May 2 and 3, the schoolchildren, soon to be Motley’s clients, skipped class, gathered at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and marched toward the business district, singing freedom songs—“We Shall Overcome,” “Oh Freedom” and other hymns—recalls Audrey Faye Hendricks, who at only 9 years old joined the marchers. Soon, though, Bull Connor, Birmingham’s notoriously racist commissioner of public safety, ordered his men to arrest the students by the hundreds. Locked in the city’s juvenile detention center, the children ate peanut butter sandwiches and slept on mattresses on the floor. Outside, Connor’s officers began violently suppressing the remaining children. Reports and images of police hosing down and clubbing the youngsters horrified a global audience.

Meanwhile, in a stunning act of retaliation, Birmingham’s school superintendent ordered the expulsion or suspension of all students who had joined the youth marches. Parents were upset, and King’s controversial decision to involve the children drew intense criticism. At this precarious moment, Motley responded by filing a lawsuit in federal court arguing that the school board’s action violated the rights of all 1,100 students who had been penalized. By suspending or expelling participants in the Children’s Crusade, Motley’s legal brief contended, the superintendent had made the legal process “an instrument of racial discrimination.”

The judge in the case, Clarence W. Allgood—a segregationist chosen for a lifetime federal appointment by President John F. Kennedy—addressed Motley in patently sexist terms. He “wanted to know,” Motley later recalled, “how it was that I, a woman lawyer, was the only one arguing the proposition” rather than her male co-counsels. Employing a tactic that Thurgood Marshall had urged fellow Black lawyers to use in the face of bigoted comments, Motley deflected the insult and pushed back with cool professionalism. She answered: “Well, because I am the Legal Defense Fund attorney assigned to the case, and I have had prior experiences in issues of this kind, and these local lawyers are not experienced in these matters.” Of all the attorneys in the courtroom, Motley insisted, she, in fact, had the greatest claim to be there. In response, the judge blurted, “You’re a woman. Would you have your children out in the streets demonstrating?” “Well,” Motley countered, “we’re not here to discuss the morality of it or whether I would have my child here, but whether we are going to enjoin the school board from keeping these children out.”

She was also one step ahead of Judge Allgood: She had taken the extraordinary measure of alerting the U.S. Court of Appeals to expect a challenge to Allgood’s anticipated unfavorable decision. Motley’s appeal swiftly prevailed, resulting in an appellate decision that the New York Times termed a “sharp rebuke” of the Birmingham judge. The children could not lawfully be punished for protesting segregation, the Appeals Court ruled, and ultimately returned to school within 24 hours of the superintendent’s retaliatory action. Their futures would not be ruined.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/1b/1f1b55ff-9fde-454b-9fbd-3ed0a82f4c99/untitled-1.jpg)

Historians often divide the movement into two antagonistic wings, with activists like King on one side, and lawyers like Thurgood Marshall, who considered King an upstart, on the other. But we see a fuller, truer portrait of the civil rights movement when we view it through Motley’s work, which spanned the worlds of lawyering and activism. Unlike Marshall, Motley was justly seen as a “movement lawyer” who embraced direct action. Still, her defense of the Birmingham civil rights campaign is now barely remembered. So intent on highlighting King, many historians pay too little attention to the legal strategies that helped the movement succeed.

For his part, King would often call attention to Motley’s vital role as the movement’s lawyer. In a 1965 column in New York’s Amsterdam News, King cited Motley among the great American litigators who had made strides for social change, alongside Clarence Darrow, Wendell Willkie, Charles Houston and others. Motley’s efforts and commitment kept protests alive in Birmingham and beyond, with enormous consequences: The Good Friday protests and the Children’s Crusade made all too clear to white Northerners the abhorrent violence of segregation, creating the national political will to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1989, during a lecture at the University of Virginia, Motley reflected on women’s pivotal role in the movement: “If the women” had not been there “night after night to support Dr. King, the movement would have failed.”

Victorious

The first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court, Motley won 9 of her 10 cases

By Ted Scheinman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/74/8d748340-84f9-4ccc-b13c-1cd5528ff707/5.jpg)

1961 • Right to counsel • Hamilton v. Alabama

Accused of breaking and entering with plans to “ravish” a white woman, Charles Clarence Hamilton, a mentally disabled Black man, faced capital punishment. But Motley persuaded all nine justices that the Alabama courts had violated Hamilton’s 14th Amendment rights because he had first been arraigned without a lawyer present. The case was a landmark in preserving capital defendants’ right to counsel.

1962 • Higher education • Meredith v. Fair

In 1962, after Motley convinced the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit to allow James Meredith to attend the University of Mississippi, the state appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled in Motley and Meredith’s favor. Meredith went on to attend the university and pursue further civil rights work.

1963 • Desegregation • Watson v. City of Memphis

Memphis had agreed to desegregate its public recreational facilities over a transitional period of several years. Representing the city’s Black population, Motley argued that such a delay was unconstitutional and the facilities should be desegregated immediately. Motley prevailed, and the city’s Parks Commission obeyed, integrating parks and playgrounds—but it closed the city’s pools in protest.

1964 • Due process • Bouie v. City of Columbia

Defending two Black students arrested for staging a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter in Columbia, South Carolina, Motley successfully argued that the arrests stemmed from the state supreme court’s unconstitutional expansion of trespassing laws, and that the state had not respected due process. Ten days after the decision, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Brow_9781524747183_aup1.jpg)