The Ties That Bind Muhammad Ali to the NFL Protests

A new biography reveals new details about the history of the boxer—“a heavyweight of contradictions”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/71/7771990a-c9c3-4712-b46a-2b044c1e52b4/ap_670619049-wr.jpg)

Muhammad Ali first spoke out publicly against the Vietnam War in 1967, when the legendary boxer and reigning heavyweight champ told a reporter from the Chicago Daily News, “I don’t have no personal quarrel with those Viet Congs.” He went on to file paperwork to excuse himself from service as a conscientious objector, becoming the most famous antiwar figure at the time.

The legacy of his activism would end up matching, if not surpassing, his incredible achievements in the boxing ring. His visibility led other Americans to ask questions about the war, its utility, and the dissonance between African-American troops fighting abroad for a country that showed them little respect at home.

The literal trials and tribulations Ali endured are legendary. He was stripped of the championship title he had been working toward his whole career. Athletic commissions across the country suspended his boxing licenses, leaving him out of the ring for more than three years.

As Jonathan Eig writes in his new book, Ali: A Life, the legendary boxer learned firsthand what happens when a world-famous black athlete speaks out against racist forces at home. Ali wasn’t a saint, but his remarks almost ruined his life. Writers and politicians questioned his intelligence and called him an anti-American traitor. One sportswriter compared him to Benedict Arnold.

For Eig, watching the backlash against athletes like Colin Kaepernick, who are taking a public position against racism by refusing to stand for the national anthem, the similarities to Ali's story are uncanny. Prejudice and racism die hard, he says, and people’s anger has spoken volumes.

“It’s been eerie to watch it, that we’re still having these debates that black athletes should be expected to shut their mouths and perform for us,” Eig says. “That’s what people told Ali 50 years ago.”

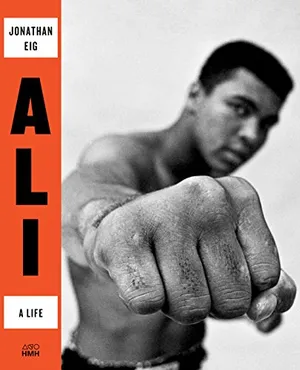

Ali: A Life

Jonathan Eig’s Ali reveals Ali in the complexity he deserves, shedding important new light on his politics, religion, personal life, and neurological condition. Ali is a story about America, about race, about a brutal sport, and about a courageous man who shook up the world.

To write this comprehensive biography of Ali, Eig talked to the boxer’s former wives, all of whom revealed intimate stories about the difficulties, and at times abusive dynamics, in their marriages. Eig dug into government records, tracking how closely the FBI surveilled Ali and the Nation of Islam, of which he was a member, tapping his phone and looking for informants within his close circle.

More than anything, Eig delves into the complexities of Ali's relationships. The boxer might have been kind to strangers on the street, but often he mistreated his wives and when his estranged friend Malcolm X was assassinated, Ali “showed no remorse,” says Eig.

“My goal is to be as honest as I could, and really show Ali as truthfully as I could,” Eig says. “And the truth is that he was insanely complicated and often contradictory. He was a heavyweight of contradictions.”

**********

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, sports curator Damion Thomas met me for a tour of the museum's exhibit on Ali. “Boxing is an interesting sport, because in many ways the heavyweight championship was a symbol of masculinity,” says Thomas. “The boxing matches have taken on symbolic meaning far beyond the ring.” The museum displays a small assortment of Ali's possessions, including a beat-up gym bag, his Everlast boxing headgear and terrycloth training robe.

Ali was born Cassius Clay, Jr., the great-grandson of an enslaved worker owned by the family of Kentucky senator Henry Clay, the so-called Great Compromiser. He grew up in Louisville, a city segregated not by Jim Crow law but by custom and white residents’ belief that it was “intrinsic, natural and inevitable,” says Eig. Clay’s father, Cassius Clay, Sr., would tell him and his younger brother, Rudolph, that his own life had been stunted by racism and his career as a painter had never taken off because of it.

When 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi, Cassius Jr. was just one year younger, and his father made sure to remind his children of it when he showed them pictures of Till’s mutilated face. “The message was clear,” Eig writes. “This is what the white man will do. This is what can happen to an innocent black person, an innocent child, whose only crime is the color of his skin.”

Only money—and lots of it—could win black people the respect of white America, Cassius Sr. told his sons. So Cassius Jr. grew up hell-bent on fighting for the respect and prosperity that eluded his father.

Cassius Jr. obsessed over two things: his body and attention. He exercised constantly by racing the school bus, and swore off anything that could hurt his health, even soda. (He opted instead for garlic water, believing it lowered his blood pressure.) And although he did not excel in the classroom—he likely was dyslexic —everyone he went to school with knew that he was going to be something special. Before he left high school, he was travelling across the country for fight after victorious fight, confidently rubbing his ability in his opponents’ faces.

All the while, Eig notes, he wasn’t all that interested in speaking about politics or race. “He wanted to fight. He wanted to be great. He wanted to be famous and wealthy. He wanted to have a good time,” Eig writes. “That was all.”

That lack of awareness changed during a fateful 1959 trip to Chicago, where he first encountered the Nation of Islam and its founder, Elijah Muhammad, the man who would later give Clay the name “Muhammad Ali.” The group’s message of black pride resonated with him. Once home, Clay listened to a recording he’d picked up in Chicago of a song called “A White Man’s Heaven is a Black Man’s Hell.” Playing it over and over again, the words began to resonate: Why are we called Negroes? Why are we deaf, dumb and blind? Apart from boxing, Eig writes, this philosophy would become a great influence in his life.

After winning gold at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, the narrative of Clay’s career is the one many are familiar with—making his professional debut later that year, winning an upset match against Sonny Liston and becoming the World Heavyweight Champion in 1963, and defeating boxing legends like Floyd Patterson. Along the way, though, he was becoming more and more aware of the complex role he would play on the world stage. In Rome, he had told a Russian reporter that, despite some troubles for black people, the United States was “still the best country in the world.” In the end, he said: “I ain’t fighting off alligators and living in a mud hut.”

Thomas says that this kind of expression was common among African-Americans in the Cold War era. “You could criticize your country,” he adds. “But you had to express faith in the capitalist democratic system. That was what was acceptable.”

But Ali shifted his tone over the course of the next few years, starting with an issue of a Nation of Islam newspaper he’d gotten on a Louisville street corner in December 1961. A cartoon caught his eye, one that he reflected on in a letter to the boxer’s second wife, Khalilah Camacho-Ali.

“The Cartoon was about the first slaves that arrived in america," Clay wrote with his characteristic misspellings, "and the Cartone was showing how Black Slaves were slipping off of the Plantation to pray in the arabic Language facing East, and the White slave Master would Run up Behind the slave with a wip and hit the poor little [slave] on the Back with the Wip and say What are you doing praying in the Languid, you know what I told you to speak to, and the slave said yes sir yes sir Master, I will pray to Jesus, sir Jesus.”

“And I liked that cartoon, it did something to me.”

After that awakening, he took cautious steps toward the Nation of Islam. He attended his first meeting in 1962 in Louisville, knowing that he couldn’t be open with the press about his newfound immersion. The FBI had classified the group as “an especially anti-American and violent cult.” It would tarnish his shining, meteoric boxing rise. Nevertheless, he began to befriend movement leader Malcolm X. “Wiry, stern, and burning with passion, Malcolm was the man who truly made whites uncomfortable,” Eig writes. “Malcolm was the man who spoke and acted as if he really were free.”

By the time Ali changed his name on March 6, 1964, his new identity fit him like a glove. “With that, he rejected the old promise that black people would get a fair chance if they played by the rules, worked hard, and showed proper respect for the white establishment,” Eig writes.

When Ali was classified in February 1966 as immediately eligible to serve in Vietnam, he told the press that he wouldn’t go. At first, it was a matter of surprise; previous low marks on intelligence test scores had rendered him ineligible. Then, it became a matter of principle. He uttered his famous Viet Cong remarks and said that as a Muslim he wouldn’t go fight in wars “unless they are declared by Allah himself.” It wasn’t a matter of fear of dying on the battlefield; after all, Thomas says, if he had served, he likely would have been entertaining the troops with boxing exhibitions as Joe Louis had during World War II.

Upon filing for conscientious objector status, people were furious. Politicians called for an upcoming fight in Chicago to be cancelled; his managers had to change the arena to one in Toronto. “At the moment when Ali should have been the king of boxing and the undisputed champion of sports commerce,” Eig writes, “he was so unpopular that he couldn’t get a fight in the United States.”

He became what Eig calls “the most widely disliked man in America.” He eventually lost his license to fight in New York, then all other states. He lost his world boxing title in April 1967, and he was convicted of draft evasion in June. He had become not just an opponent of the war, but a black man in opposition to the war, and the press coverage reflected that. White newspapers called him a coward and a traitor, while black ones like the Louisville Defender said that the public had targeted him.

“When people are speaking truth to power, often they are not supported,” Thomas says.

By the end of his career, though, Ali’s public image had softened. The Supreme Court overturned his draft evasion sentence in 1971, aided by a liberal law clerk slipping his boss, Justice John M. Harlan, the literature that had influenced Ali and that proved evident that Ali had in fact been a conscientious objector. He had been suspended from the Nation of Islam in 1969; Elijah Muhammad even rescinded his gift of Ali’s name “Muhammad,” which the boxer continued to use.

The Vietnam War officially ended in 1975, and Ali hadn’t spoken out about it much in the years leading up to it. Jim Brown, a friend, football star, and controversial activist in his own right, went as far as calling Ali part of the mainstream. “I didn’t feel the same way about him anymore, because the warrior I loved was gone,” Brown said. “In a way, he became part of the establishment.”

Ali later said that, looking back, he would have chosen his words differently during that 1967 interview about the war. When a Louisville reporter asked him in 1974 if he had any regrets in life, Ali said he wished he hadn’t “said that thing about the Viet Cong.”

“I would have handled the draft different. There wasn’t any reason to make so many people mad,” he told the reporter.

The lighting of the Olympic torch at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, proved a crucial moment for Ali's legacy, Thomas says.

Those games, he says, were focused on introducing the world to the “New South” 30 years after the height of the Civil Rights Movement, and showing onlookers how much racial progress had been made since. He was markedly frail and shaking—Ali’s motor skills had been impaired by Parkinson’s disease—but nevertheless lit the torch. And the crowd erupted into a cacaphony of cheers.

It helped to cement his status as a palatable symbol of civil rights, Thomas says. “I don’t know if a lot of people have accepted his ideas about race, and that’s the thing about Muhammad Ali,” Thomas says. “He can mean many things to many different people. And people find the Ali that they’re most comfortable with.”

At his funeral in June of last year, then-president Barack Obama eulogized him in a statement, acknowledging the boxer’s contradictions and complications but settling on gratitude.

“He stood with King and Mandela; stood up when it was hard; spoke out when others wouldn’t,” Obama wrote. “His fight outside the ring would cost him his title and his public standing. It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled, and nearly send him to jail. But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.”

Adds Eig, “I hope that people will remember that he was one of America’s important rebels, and this is a country built on rebellion,” he says. “We should embrace people who take a risk and try to change the country for the better.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_0930.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_0930.JPG)