The Cannibal Club: Racism and Rabble-Rousing in Victorian England

These 19th-century gentlemen of good standing let their inner boors loose in secret London backrooms

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/31/06310742-ae03-4800-b80c-4ceb893946cf/secret_society.jpg)

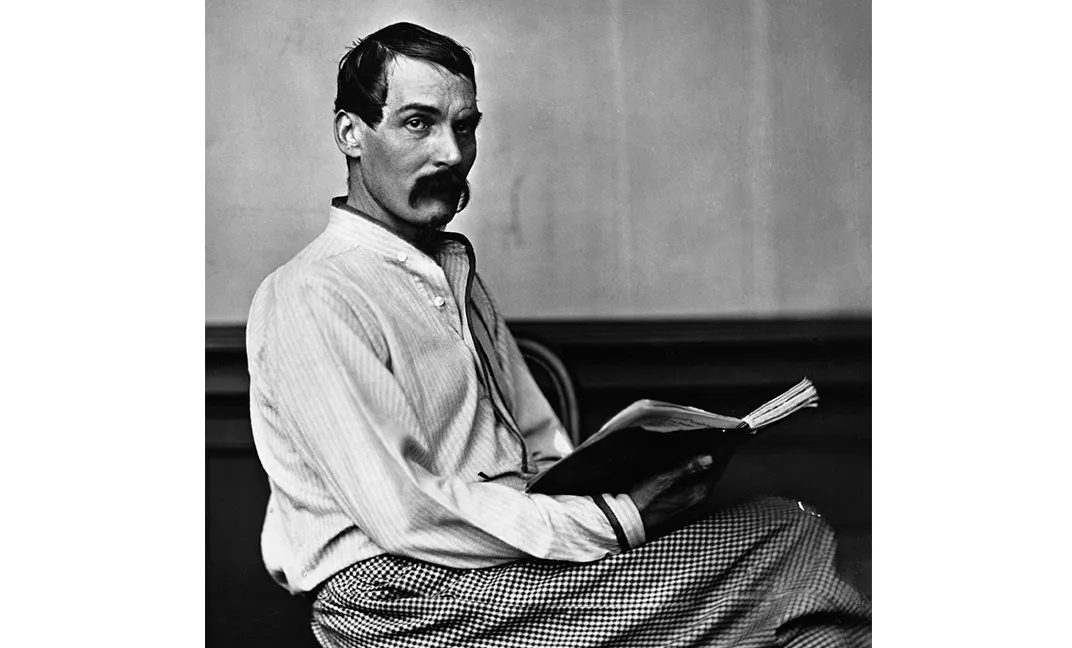

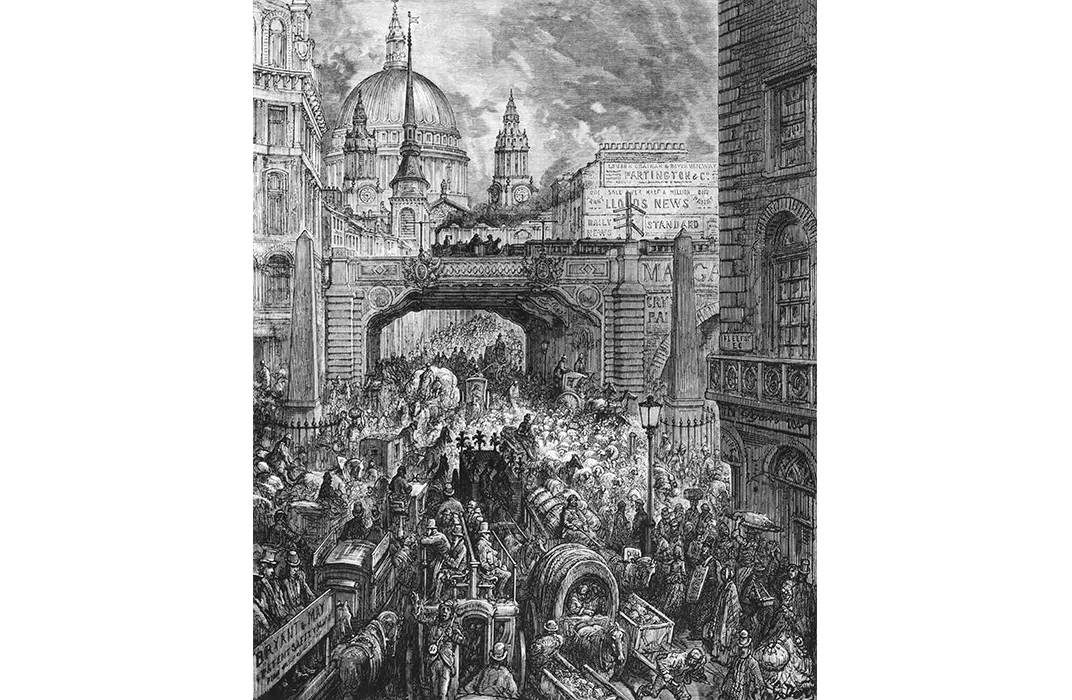

Bertolini's restaurant was cheap, but charming: perfect for the creatures who roamed 19th-century London after the sun went down. On Tuesday nights, in Bertolini's backroom, respected judges and doctors, esteemed lawyers, admired politicians and award-winning poets and writers drank heavily, smoked cigars and secretly discussed what they thought they knew of the British colonies, more specifically polygamy, bestiality, phallic worship, female circumcision, ritual murder, savage fetishes and island cannibalism. The gentlemen would trade in exotic pornography and tales of flogging and prostitution. If, by chance, a pious, God-fearing bloke were to accidentally stumble into the Fleet Street backroom on a Tuesday night, the tips of his Victorian moustache would've certainly stood on end.

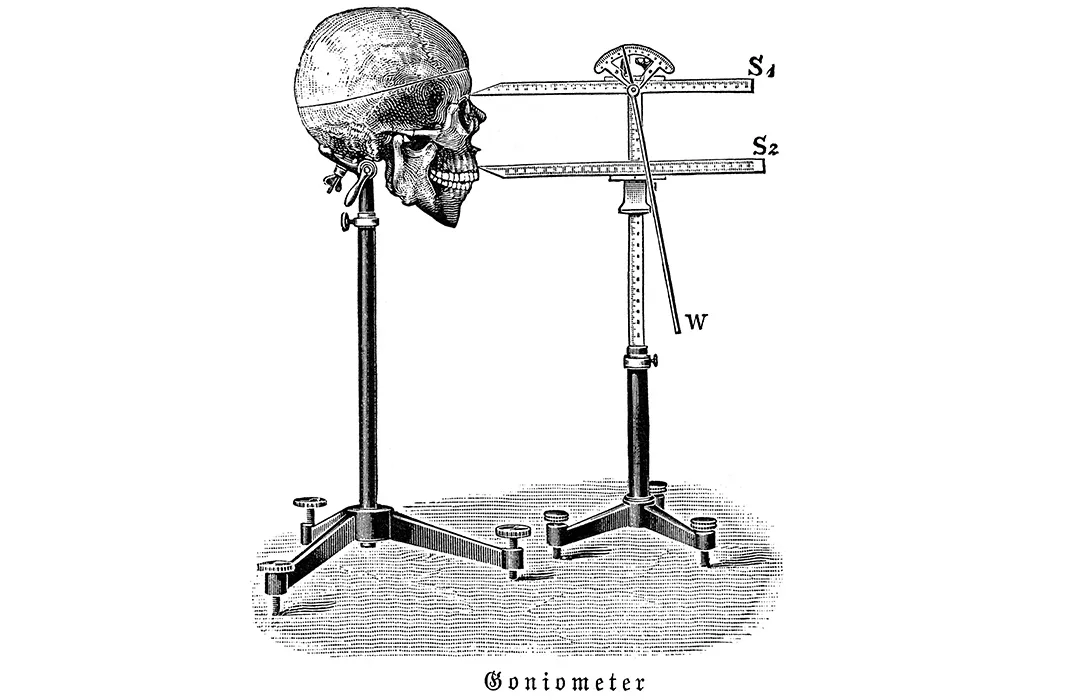

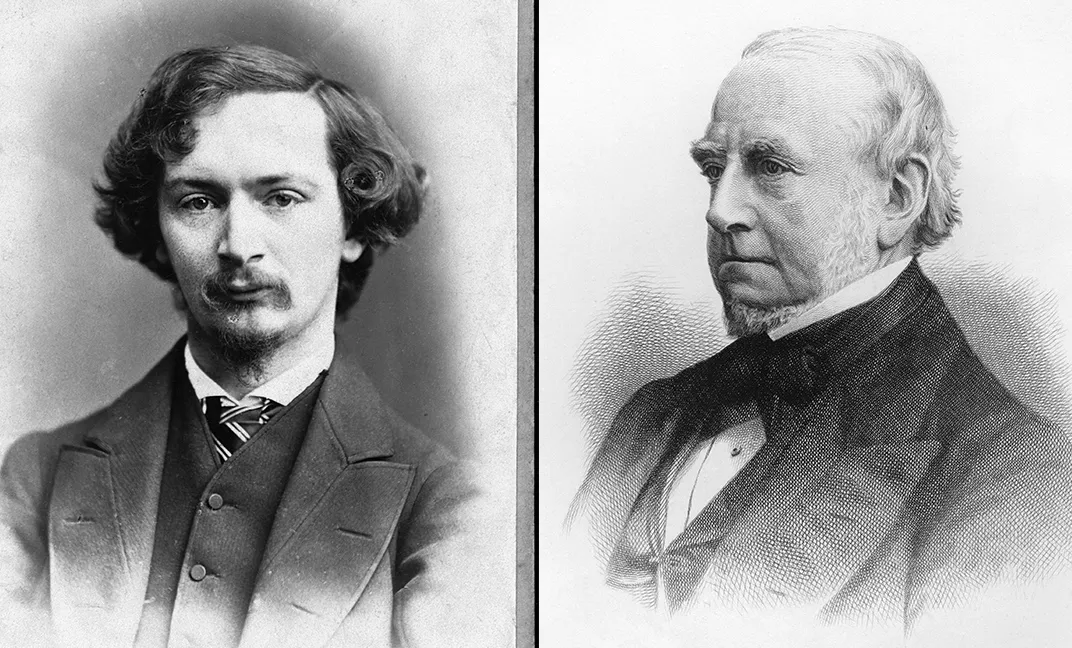

Before the debate between science and creationism, there was the debate between monogenism and polygenism. Monogenists believed that all of humanity shared a common ancestry while polygenists were convinced that different races of man had different origins. There was a palpable tension in Victorian England between the creation of a democratic scientific methodology and the elitist attitudes that reinforced Anglo-Saxon superiority. During Britain's "Imperial Century" these convenient human classifications were perfectly inline with colonialist sensibilities—of course, no race could match the enlightenment of the English Gentleman. The conflict captured the imagination of Victorian England and, by 1863, drove a wedge between the polygenist and monogenist members of the then 20-year-old Ethnological Society of London. Determined to continue advocating their polygenist ideologies, Captain Richard Francis Burton and Dr. James Hunt, both members of the Ethnological Society of London, broke away and established The Anthropological Society of London. The new splinter society supported the pseudoscientific practices of phrenology, the measuring of skull size with craniometers and, of course, polygenism. Recent scholarship has even suggested that its members were covert propagandists, acting on behalf of the Confederate States of America to convince Londoners that enslaved Africans were biologically incapable of any development beyond their menial work as slaves.

From the intellectual ferment of the Anthropological Society's inaugural year grew an even more exclusive and overtly seditious conclave of high-society rebels: a gentlemen's dining group called the Cannibal Club. Though Hunt was the president of the Anthropological Society, Burton, who possessed a Byronic love for shocking people, was to be the mastermind behind the new hush-hush fraternity. An experienced geographer and explorer, a writer and translator who spoke 29 languages, a decorated captain in the army of the East India Company and renowned cartographer, Richard Francis Burton was also considered by some to be a rogue, a murderer, an impostor and betrayer, a sexual deviant, and a heroic boozer and brawler. He was six feet tall with a barrel chest and an imposing scar on his left cheek. He was famous for infiltrating Mecca in 1853, disguised as an Arab merchant and for translating the raw, unexpurgated texts of erotic Eastern literature such as the Kama Sutra and the Arabian Nights. He was presented to the Queen and he dined with the Prime Minister. When asked by a young vicar if he'd ever killed a man, Burton replied cooly, "Sir, I'm proud to say that I have committed every sin in the Decalogue." Burton was one of Hell's original hounds and the Cannibal Club was his sanctuary.

Sitting around in stovepipe top hats, tailored frocks and loosened cravats in the banquet room of Bertolini's, the members would be called to order with a strike of Burton's gavel. The gavel, naturally, was a piece of wood carved in the likeness of their official symbol: a mace drawn to resemble an African head gnawing on a thighbone. And before launching into one of their raucous powwows, a member would stand and recite the club's Cannibal Catechism: an anthem of sorts that purposely mocked the Christian sacrament of the Eucharist, likening it to a cannibal feast. The opening stanza of the invocation, written by Cannibal Club mainstay, respected playwright and decadent poet, Algernon Charles Swineburne, depicts just how profoundly blasphemous and anti-clerical the group was:

Preserve us from our enemies;

Thou who art Lord of suns and skies;

Whose meat and drink is flesh in pies;

And blood in bowls!

Of thy sweet mercy, damn their eyes;

And damn their souls!

Swineburne, a short and fragile man with a little weasel-like mouth, was perhaps one of the clubs most debauched members. As a suicidal algolagniac, alcoholic and habitué of London's flagellant brothels, Swineburne also contributed to the eminent 11th Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1903 to 1907 and again in 1909. After Swineburne's Catechism was recited, the members would "eat, drink, and let their conversations veer absolutely wherever they wanted", writes Monte Reel in Between Man and Beast. "The members were drawn to one another thanks to a shared hatred for one 'Mrs. Grundy'—a fictional composite who epitomized the tight-laced prudery that threatened to define the era." Needless to say, no minutes were kept during the meetings.

Cannibal Club members were culture-warriors. They were generally sympathetic to all religions yet loyal to none. They were unapologetic hedonists and scientific racists. They exhibited an unbridled interest in the various expressions of human sexuality and saw sexual repression as a national crisis. Another central figure of the club was Charles Bradlaugh, a political activist, renowned atheist and the founder of the National Secular Society. Bradlaugh was a pamphleteer who openly published information on land reform and birth control. In 1880, when Bradlaugh was elected into Parliament, he refused to take the religious oath—an act for which he was briefly imprisoned in a cell beneath Big Ben. In 1891, his funeral was attended by 3,000 people including a then 21-year-old Mohandas Gandhi. Another cornerstone of the club was Baron Monckton Milnes, a poet, patron of literature and politician. Milnes' unrivalled private collection of pornography, which was known to few during his lifetime, now sits in the British Library. English author, Jean Overton, contends that Milnes was the author of The Rodiad, an unattributed pornographic poem published in 1871 about a schoolmaster who derives pleasure from flogging young boys. Cannibal Club members truly lived dual lives: honorable gentlemen by day, perverse pleasure-seekers by night.

England was teeming with Mrs. Grundy's at the time and cultural non-conformists like Burton and his Cannibals had had enough of her. "Mrs. Grundy is already beginning to roar," Burton once said while working on his translation of the Arabian Nights. "Already I hear the fire of her. And I know her to be an arrant whore, and tell her so, and don’t give a goddamn for her." Mrs. Grundy eventually manifested herself in the Society for the Suppression of Vice and various British obscenity laws such as the Obscene Publications Act of 1857—all established to weed out counter-culturists and prosecute them for their indecency. And although the Cannibal Club had insulated itself to allow for the free and safe airing of subjects deemed deviant by society, it was simultaneously taking it upon itself to challenge prudish conventions and work towards a more liberal London.

But the Cannibal Club, as a furtive extension of The Anthropological Society, had motivations beyond simply rabble-rousing. In Reading Arabia: British Orientalism in the Age of Mass Publication, 1880-1930, author Andrew C. Long writes:

[The Cannibal Club's] central activity was the production and distribution of colonialist pornography for their circle and other elite consumers. However—and this is key for the formation of colonial and imperial ideology—they justified their activities as the pursuit of science and art, where pornography, or their pseudoscientific combination of sexology and anthropology, would help to understand better the specific sexual practices and culture in the far-flung reaches of the Empire.

In the latter half of the 19th century the erotic viewing privileges of the club and its consumers were undermined as British and French companies began to mass-produce pornographic postcards, many of them exploiting colonial imagery much like the Cannibal Club had been doing all along.

The Cannibal Club lasted just a few short years, however. After Hunt's death in 1869 and Burton's international diplomatic services took him abroad, the old gang began to thin out. By the early 1870s, Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), was selling at a rate of 250 copies per month in Britain and his follow-up, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), which focused more on sexual selection and evolutionary ethics, had just hit shelves. Subsequently, the racially motivated polygenist ideology adhered to by The Anthropological Society and, by extension, The Cannibal Club, became passé. In his paper, "The Cannibal Club and the Origins of 19th Century Racism and Pornography" (2002), John Wallen asserts that Burton tried to revive the Cannibal Club sometime in the 1870s without success.

In 1871, the Anthropological Society and the Ethnological Society of London reunited to form The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, which is active to this day, promoting the public understanding of anthropology. In 1886, Burton, respected geographer, racist and rabble-rouser, was knighted by Queen Victoria.