California Once Targeted Latinas for Forced Sterilization

In the 20th century, U.S. eugenics programs rendered tens of thousands of people infertile

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/6b/246b84ec-6677-435d-8e58-487b2a5e4860/file-20180316-104663-1txsaha.png)

In 1942, 18-year-old Iris Lopez, a Mexican-American woman, started working at the Calship Yards in Los Angeles. Working on the home front building Victory Ships not only added to the war effort, but allowed Iris to support her family.

Iris’ participation in the World War II effort made her part of a celebrated time in U.S. history, when economic opportunities opened up for women and youth of color. However, before joining the shipyards, Iris was entangled in another lesser-known history.

At the age of 16, Iris was committed to a California institution and sterilized.

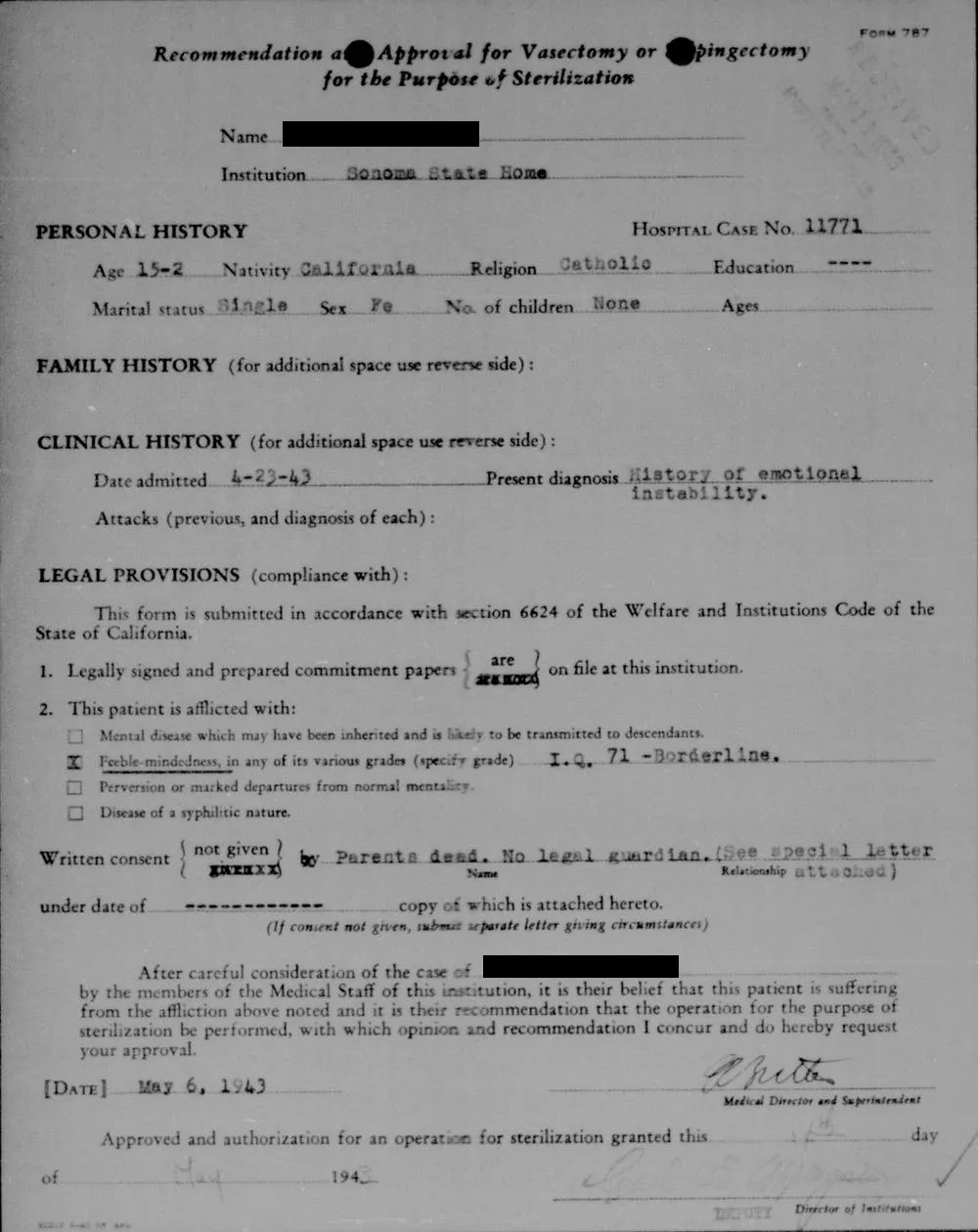

Iris wasn’t alone. In the first half of the 20th century, approximately 60,000 people were sterilized under U.S. eugenics programs. Eugenic laws in 32 states empowered government officials in public health, social work and state institutions to render people they deemed “unfit” infertile.

California led the nation in this effort at social engineering. Between the early 1920s and the 1950s, Iris and approximately 20,000 other people—one-third of the national total—were sterilized in California state institutions for the mentally ill and disabled.

To better understand the nation’s most aggressive eugenic sterilization program, our research team tracked sterilization requests of over 20,000 people. We wanted to know about the role patients’ race played in sterilization decisions. What made young women like Iris a target? How and why was she cast as “unfit”?

Racial biases affected Iris’ life and the lives of thousands of others. Their experiences serve as an important historical backdrop to ongoing issues in the U.S. today.

.....

Eugenics was seen as a “science” in the early 20th century, and its ideas remained popular into the midcentury. Advocating for the “science of better breeding,” eugenicists endorsed sterilizing people considered unfit to reproduce.

Under California’s eugenic law, first passed in 1909, anyone committed to a state institution could be sterilized. Many of those committed were sent by a court order. Others were committed by family members who wouldn’t or couldn’t care for them. Once a patient was admitted, medical superintendents held the legal power to recommend and authorize the operation.

Eugenics policies were shaped by entrenched hierarchies of race, class, gender and ability. Working-class youth, especially youth of color, were targeted for commitment and sterilization during the peak years.

Eugenic thinking was also used to support racist policies like anti-miscegenation laws and the Immigration Act of 1924. Anti-Mexican sentiment in particular was spurred by theories that Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans were at a “lower racial level.” Contemporary politicians and state officials often described Mexicans as inherently less intelligent, immoral, “hyperfertile” and criminally inclined.

These stereotypes appeared in reports written by state authorities. Mexicans and their descendants were described as “immigrants of an undesirable type.” If their existence in the U.S. was undesirable, then so was their reproduction.

.....

In a study published March 22, we looked at the California program’s disproportionately high impact on the Latino population, primarily women and men from Mexico. Previous research examined racial bias in California’s sterilization program. But the extent of anti-Latino bias hadn’t been formally quantified. Latinas like Iris were certainly targeted for sterilization, but to what extent?

We used sterilization forms found by historian Alexandra Minna Stern to build a data set on over 20,000 people recommended for sterilization in California between 1919 and 1953. The racial categories used to classify Californians of Mexican origin were in flux during this time period, so we used Spanish surname criteria as a proxy. In 1950, 88 percent of Californians with a Spanish surname were of Mexican descent.

We compared patients recommended for sterilization to the patient population of each institution, which we reconstructed with data from census forms. We then measured sterilization rates between Latino and non-Latino patients, adjusting for age. (Both Latino patients and people recommended for sterilization tended to be younger.)

Latino men were 23 percent more likely to be sterilized than non-Latino men. The difference was even greater among women, with Latinas sterilized at 59 percent higher rates than non-Latinas.

In their records, doctors repeatedly cast young Latino men as biologically prone to crime, while young Latinas like Iris were described as “sex delinquents.” Their sterilizations were described as necessary to protect the state from increased crime, poverty and racial degeneracy.

.....

The legacy of these infringements on reproductive rights is still visible today. Recent incidents in Tennessee, California and Oklahoma echo this past. In each case, people in contact with the criminal justice system—often people of color—were sterilized under coercive pressure from the state.

Contemporary justifications for this practice rely on core tenets of eugenics. Proponents argued that preventing the reproduction of some will help solve larger social issues like poverty. The doctor who sterilized incarcerated women in California without proper consent stated that doing so would save the state money in future welfare costs for “unwanted children.”

The eugenics era also echoes in the broader cultural and political landscape of the U.S. today. Latina women’s reproduction is repeatedly portrayed as a threat to the nation. Latina immigrants in particular are seen as hyperfertile. Their children are sometimes called “anchor babies” and described as a burden on the nation.

This history—and other histories of sterilization abuse of black, Native, Mexican immigrant and Puerto Rican women—inform the modern reproductive justice movement. This movement, as defined by the advocacy group SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective is committed to “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”

As the fight for contemporary reproductive justice continues, it’s important to acknowledge the wrongs of the past.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Nicole L. Novak, Postdoctoral Research Scholar, University of Iowa

Natalie Lira, Assistant Professor of Latina/Latino Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign