The Bootleg King and the Ambitious Prosecutor Who Took Him Down

The clash between George Remus and Mabel Walker Willebrandt present a snapshot of life during the Roaring Twenties

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/68/166831f2-ffef-4223-9a45-24e78f083c6e/gettyimages-514697400-resize.jpg)

In the early 1920s, no one in America owned more of the illegal alcohol trade than Cincinnati’s George Remus. A pharmacist and defense lawyer with a keen eye for exploiting legal loopholes, Remus controlled, at one point, 30 percent of the liquor making its way to the cups and goblets of Americans who had no use for Prohibition. Remus was a larger-than-life figure—he threw lavish parties, was beloved by newspapermen who could always count on him for a good quip, and was rumored to be the inspiration for F. Scott Fitzergald’s Jay Gatsby. But by 1925, cracks in Remus’s empire would start to weaken his hold on the booze business as he found himself in a courtroom with Mabel Walker Willebrandt, an ambitious government attorney ready to use Prohibition—and its most notorious bootleggers—to establish the kind of legal and political career usually denied to even the most talented women. By 1927, the embattled Remus found himself on trial once more—for the murder of his second wife, Imogene.

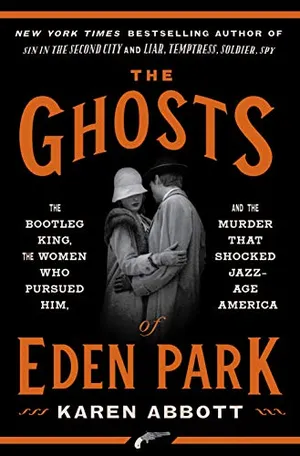

In her new history, The Ghosts of Eden Park: The Bootleg King, the Women Who Pursued Him, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz-Age America, Smithsonian magazine contributor Karen Abbott traces Remus’s rise and fall and on the way introduces us to a cast of Jazz Age characters all looking to make their mark not just on the 1920s, but on the very future of American business and politics.

Abbott spoke with Smithsonian about her new book in a conversation that covered Remus’s stardom, Mabel’s ambition, and the impact of bootleggers on American literature.

The Ghosts of Eden Park: The Bootleg King, the Women Who Pursued Him, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz-Age America

Combining deep historical research with novelistic flair, The Ghosts of Eden Park is the unforgettable, stranger-than-fiction story of a rags-to-riches entrepreneur and a long-forgotten heroine, of the excesses and absurdities of the Jazz Age, and of the infinite human capacity to deceive.

How did you come to this story, with its sprawling cast of characters and constant double-dealing?

This one came from television, [HBO’s] “Boardwalk Empire.” It was a brilliant show, perfectly captured the dawn of 1920s when bootleggers were just figuring out how to circumvent prohibition laws and nobody had heard of Al Capone. And there was this really strange, charismatic, fascinating character named George Remus (Glenn Fleshler) who was really innovative and slightly bizarre and spoke of himself in the third person.

And I always laughed at those scenes where Capone, another real-life character the show depicts, is clearly confused about who Remus was referring to and Remus is referring to himself. And I wondered if he was a real person, and indeed he was. And his real story was so much more interesting and dark and complex than what “Boardwalk Empire” portrayed.

So I was sold on his character first, and then I always need a bad-ass woman in there, so I landed on a character in the show called Esther Randolph. She was a district attorney appointed by President Warren Harding and working for Attorney General Harry Daugherty. And in real life her name was Mabel Walker Willebrandt. I liked the sort of cat and mouse dynamic between her and Remus.

Mabel and Remus are definitely at the heart of the story, and it seems like they have a lot in common despite being on opposite sides of the law.

Mabel was born in the United States, but she was of German heritage, and Remus was a German immigrant. Remus quit his formal schooling at 14 as she only began her formal schooling at 14. Both of them hated to lose; both of them were extremely proud. Both of them adopted children, which I also thought was interesting.

And Mabel was a drinker. Not a drunk by any means, but somebody who enjoyed the occasional glass of wine, didn't at all believe in Prohibition or think it was a good law, and didn’t think it was enforceable in any way, shape or form. But she was given a mandate to [enforce] it, and of course she capitalized on that opportunity thinking, here is my chance to make a statement, not only as a woman politician and advance myself in that regard, but advance the cause of women politicians for decades to come.

Suddenly she's the most powerful woman in the United States and one of the most powerful people in the country.

How do you source a story like this?

There was a 5,500-page trial transcript that sort of became the spine of the narrative. It was great because, of course in trials you have benefit of witness testimony. They're forced to recount, to the best of their knowledge, dialogue and what they were wearing, what they were thinking, what they were doing, what the other person said, and what were their impressions. And so all of that allows for some really cinematic scenes, just from detail that otherwise wouldn't be available.

How much of George Remus is a product of the world he was living in? What’s the historical backdrop this story is set against, and how does it shape the characters?

His story really couldn't have happened at any other time period in history. It was sort of tailored for the 1920s and, of course, his profession bootlegging could only have happened in this very brief time period. The ’20s were an interesting time, obviously. Everybody has enjoyed the flappers and the Gatsby and all of that sort of flashy stuff. But thinking of it historically, we just had gotten out of World War I, people had the sense of mortality, realizing how fleeting life could be, and the death aura was still circling around America. And it was before the 1930s [and the Great Depression], so people were willing to take a risk and living more vivaciously and having more fun after all of that death and destruction.

The people during this time period saw Remus as a hero. So many people lost jobs during Prohibition: bartenders, waiters, glass makers, barrel makers, transportation people. In Cincinnati alone, he employed about 3,500 people, which certainly made him a folk hero there. The fact that it was a lighter time in terms of organized crime because nobody really thought Prohibition was a fair law. Not only do they think it's a stupid law, they thought it was an unfair law.

Right—someone like Remus comes feels very different from a figure like Al Capone.

Capone was a dirtier guy. He was into mass murder, he was into systematic violence. He was into drugs, he was into prostitution. Remus built his empire with intellect, rather than systematic violence, and didn't even drink his own supply. Capone was a criminal mastermind in terms of gangland activities, but Remus was actually an erudite and fairly intellectual guy. And I think that also makes him more complex and, in some ways, a more sympathetic character.

How did Remus’ contemporaries see his success?

His rivals were in awe of him, in a way. He obviously wielded a lot of power. The hundreds of thousands of dollars of bribes that he paid to elected government officials was well known, and he was somebody who could have access to pretty much any table you wish to sit at. Prohibition was such an unpopular law, people saw Remus basically as an office supplying the demand. One of his quotes is, "Everyone who has an ounce of whiskey in his possession is a bootlegger." And he was constantly calling out all of the politicians who he knew were drinking his supply at the same time that they were advocating for Prohibition.

What about when things start to go wrong for him? How much did his image shape what happened (no spoilers!) at his murder trial?

He was a king of a soundbite, and he knew how to manipulate the press. That was something that constantly flustered Willebrandt too. She constantly referenced the fact that Remus made good copy. He really just knew how to manipulate the media. And, of course this is early on in the media wars when everybody was angling for the best photograph and the best headline, the most racy bit of gossip. That all played brilliantly into Remus' hands.

But we also have to come back to the idea of just how unpopular Prohibition is—even if you think, as many people did, that Remus was guilty of everything he was accused of, the murder trail became less about Remus as one man and more of a referendum on Prohibition (and bootleggers) itself.

At the end of the day, did Mabel stand a chance in stopping the tide of bootlegging? What else was she battling?

She talked very openly that she was not only battling bootleggers and smugglers, and the unpopularity of the law, but also her corrupt colleagues at the Department of Justice. The Prohibition agents that she sent out into the field would make significantly more money taking bribes from bootleggers and they would just accepting their meager payroll. Considering that Remus was basically handing out thousand-dollar bills like it was candy, you can imagine the temptations.

But Mabel was every bit of an opportunist as Remus. She’s somebody who was up for a federal judgeship several times, a I didn't even write about all of them because it became, so it would've been so redundant.

And she was really open about the sexism she faced. One of my favorite quotes from her was in an article for the literary magazine The Smart Set, where she said “A boy must do the job well, and develop personality. A girl must do the job well and develop personality. PLUS—break down skepticism of her ability, walk the tight rope of sexlessness without loss of her essential charm…and lastly, maintain a cheerful and normal outlook on life and its adjustments in spite of her handicap.”

Rumors have long swirled that Remus is the inspiration for another famous bootlegger—Jay Gatsby, of F. Scott Fitzergald’s The Great Gatsby. Is there any truth to that?

There are all these impossible stories that [the two] met when Fitzgerald was stationed in Louisville. I don't necessarily think they are true; Fitzgerald was stationed there before Remus really got into bootlegging. Which isn't to say Remus didn't travel to Louisville and possibly could have run into him. But the similarities between Remus and Gatsby are conspicuous. Both owned a chain of pharmacies, both threw these lavish parties. Both were in love with an enigmatic woman.

And I think Gatsby and Remus both had these longings of belonging to a world that didn't wholly accept them or fully understand them. Even if Fitzgerald never met Remus, everybody knew who George Remus was by the time Fitzgerald started to draft The Great Gatsby.

Remus was a larger than life character, to use a cliché, just as Gatsby was in his way, and just as emblematic of the Twenties. It's hard to imagine Remus existing in any other decade but in the 1920s and likewise for Gatsby.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.