Boar War

A marauding hog bites the dust in a border dispute between the United States and Britain that fails to turn ugly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/boar_artifacts.jpg)

In a classroom on San Juan Island, Washington, across the HaroStrait from Victoria, Canada, a man in uniform was showing 26 fifth graders how to load a rifle. “It looks old, but it’s a weapon of modern warfare, mass-produced in a factory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in the mid-19th century,” said Michael Vouri, a National Park Service ranger at San Juan Island National Historical Park. “It fires .58-caliber bullets—huge lead balls—and was designed specifically to hurt and kill people. It can hit a man from five football fields away, and when it strikes bone, the bone splinters in every direction.” Silent and saucereyed, the kids craned for a better look.

Vouri lowered the rifle and held it out for closer inspection. “This is the sort of gun that almost started a war, right here on this island, between the United States and England, in 1859,” he said.

So began another of Vouri’s retellings of the boundary dispute between the United States and Britain that threatened to pitch the two nations into their third bloody conflict in less than 100 years. Few people outside of San JuanIsland have ever heard of the Pig War—whose peaceful outcome makes it an all-too-rare example of nonviolent conflict resolution—though in 1966 the U.S. government created the San Juan Island National Historical Park to commemorate it. Vouri, a Vietnam veteran who wrote a book about the standoff, believes it holds lessons for today.

By 1859, forty-five years after the inconclusive settlement of the War of 1812, the United States and Great Britain had developed an uneasy entente. The “Anglo-American Convention” of 1818 had solidified England’s control over the eastern half of what we know today as Canada, and citizens from each nation were moving ever west across the North American continent. The convention also established the border between the United States and Britain along the 49th parallel from the Lake of the Woods, bordering what is now Minnesota, west to the Rocky Mountains. Under its terms, the two countries would jointly administer the so-called Oregon Country northwest of the Rockies for ten years. In theory, unless either nation could decisively show that it had settled the region, the treaty would be renewed.

But renewal always seemed unlikely. To the thousands of Yankee settlers and fortune seekers who poured into the Oregon Territory during the mid-19th century, this half-million-square-mile swath of land—comprising today’s Oregon, Washington, Idaho and parts of Montana, Wyoming and British Columbia—represented a promised land. The same was true for English merchants, who craved the region’s deep ports and navigable rivers as lucrative highways for trade.

For decades, the Hudson’s Bay Company, a private furtrading corporation that functioned as England’s surrogate government in the territory, had lobbied for a border that would keep the Columbia River—a crucial pipeline for pelts—in English hands. But by the 1840s, British trappers found themselves vastly outnumbered. The U.S. population had swollen from more than 5 million in 1800 to 23 million by mid-century, and a heady sense of Manifest Destiny continued to drive farmers west. “In 1840 there were 150 Americans in all of Oregon Country,” says University of Washington historian John Findlay. “By 1845 that number had jumped to 5,000, and Americans were feeling their oats.”

Tensions had peaked in 1844 when under the slogan “Fifty-four forty or fight,” Democratic presidential candidate James Polk promised to push the U.S. border almost 1,000 miles north to 40 minutes above the 54th parallel, all the way to Russia’s territory of Alaska.

But Polk, who went on to beat Kentucky Whig Henry Clay for the presidency, sent the U.S. military not north but south in 1846, into a two-year war with Mexico. That conflict ultimately expanded the United States’ southern border to include Texas, California and most of New Mexico, and it stretched the frontier army almost to the breaking point. Another war on another front hardly seemed possible. “Polk wasn’t stupid,” says Scott Kaufman, author of The Pig War: The United States, Britain, and the Balance of Power in the Pacific Northwest, 1846-72. “He wanted territory—no question. But he wasn’t prepared to go to war with Britain about it.”

England’s territorial ardor in the Oregon Country had also cooled. Fur profits in the Pacific Northwest had begun to decline, partly due to overtrapping by settlers. As a result, maintaining exclusive control of the Columbia River now seemed less important. “In 1846,” Kaufman says, “both sides thought, ‘We’ve got to cool things down. Let’s just get this treaty signed. Let’s move on.’ ”

Indeed, on June 15, 1846, the United States and Britain signed a new agreement. The Treaty of Oregon stated that the new boundary “shall be continued westward along the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island, and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of Fuca’s Straits, to the Pacific Ocean. . . .”

As clear as that may have sounded to diplomats on both sides of the Atlantic, the treaty contained a loophole big enough to drive a warship through. At least two navigable channels run south through that region, with a sprinkling of forested islands—chief among them San Juan—strategically situated in the middle. To which country did these islands, with their cedar and fir forests, rich topsoil, deep ponds and mountaintop-lookouts, belong? The chief negotiators for the Crown and the president eventually dismissed such questions as details to be worked out later.

In December 1853, to help strengthen Britain’s claim on the territory, Hudson’s sent Charles Griffin to San JuanIsland to run a sheep ranch. Griffin named his place Belle Vue for its vistas of soaring eagles, whale-filled bays and snowcapped peaks. For a while, Griffin and his staff and livestock enjoyed the run of the entire 55-square-mile island.

But by the mid-1850s, Americans were beginning to stake their own claims on the island. In March 1855, a brazen sheriff and his posse from WhatcomCounty on the Washington mainland confiscated some of Griffin’s sheep in the middle of the night, calling the animals back taxes. The raid was deliberately provocative. “The issue was less about tax collection and more about sovereignty,” says University of New Mexico historian Durwood Ball. “Americans believed that the U.S. expansion all the way to the PacificCoast was the will of God, and success in the Mexican War had only fired up that conviction. They figured they could take the British.” By 1859, drawn to the island in the aftermath of a gold rush along the nearby FraserRiver, more than a dozen Americans had set up camps there. One of them was Lyman Cutlar, a failed gold prospector from Kentucky who in April of that year staked out a claim with a small cabin and potato patch right in the middle of Griffin’s sheep-run.

Cutlar said that the governor of Washington himself had assured him—erroneously, as it turned out—that the island was part of the United States. Therefore, Cutlar claimed that as a white male citizen over 21 years of age, he was entitled, under the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, to 160 free acres. (He was wrong, again; “preemption” land acts that provided free or discounted property to Western homesteaders did not apply to the disputed territory.)

As it happened, Cutlar’s potato patch was poorly fenced (“three-sided,” according to official complaints), and Griffin’s animals soon took to wandering through it. According to Cutlar’s subsequent statements to U.S. officials, on the morning of June 15, 1859, he awoke to hear derisive tittering from outside his window.

Rushing from his house with a rifle in hand, Cutlar reached the potato patch to see one of Griffin’s hired hands laughing as one of Griffin’s black boars rooted through Cutlar’s tubers. An incensed Cutlar took aim and fired, killing the boar with a single shot.

Thus was fired the opening and only shot of the Pig War, setting off a chain of events that almost brought two great nations to blows. (“Kids always want to know who ate the pig,” Vouri says. “No one knows.”) Cutlar offered to replace the pig, or, failing that, to have Griffin choose three men to determine a fair price for it. Griffin demanded $100. Cutlar sputtered: “Better chance for lightning to strike you than for you to get a hundred dollars for that hog.”

Cutlar stomped off, and Griffin alerted his superiors at the Hudson’s Bay Company. They, in turn, called on the American’s cabin, demanded restitution and, depending on whose story you believe, threatened him with arrest. Cutlar refused to pay and refused to go with them, and the British, not wanting to force the issue, left empty-handed.

A few weeks later, in early July, Gen. William S. Harney, the commander of the U.S. Army’s Oregon Department, toured his northern posts. Noticing an American flag that Cutlar’s compatriots had raised on the island to celebrate July 4, he decided to investigate. The American settlers complained bitterly to him about their vulnerability to Indian attacks and their treatment by the British, and asked for military protection. It wasn’t long before they brought up the incident with the pig.

Although Harney had just days before paid a cordial call on British territorial governor James Douglas to thank him for his protection of American settlers against Indian attacks, the general—a protégé of Andrew Jackson’s who had absorbed his mentor’s hatred of the British—saw a chance to settle old scores with an aggressive stroke. (Harney, who would be court-martialed four times in his career, was “excitable, aggressive, and quick to react to any affront, insult, or attack, whether real or imagined, personal or professional,” writes his biographer, George Rollie Adams.)

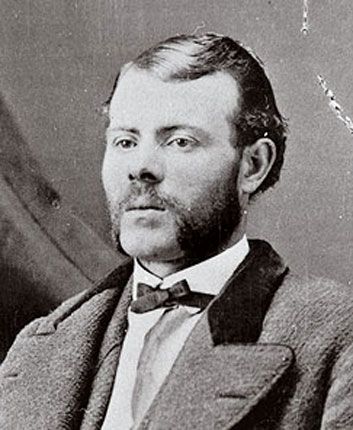

Citing what he called the “oppressive interference of the authorities of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Victoria,” Harney ordered Capt. George Pickett, a 34-year-old, ringlethaired dandy who’d graduated last in his class at West Point before being promoted in the Mexican War (for what some deemed reckless bravery), to lead a detachment of infantrymen from Fort Bellingham, Washington, to San Juan Island. For his part, the British governor also welcomed a confrontation. He had worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company for 38 years and believed that Britain had “lost” Oregon because his commanding officer at FortVancouver, where he served as deputy, had been too welcoming of American settlers. In an 1859 dispatch to the British Foreign Office, Douglas complained that the “whole island will soon be occupied by a squatter population of American citizens if they do not receive an immediate check.”

On July 27, 1859, the steamer USS Massachusetts deposited Pickett’s 66 men on San JuanIsland, where they set up a camp on 900 square feet of windy hillside above the Hudson’s Bay Company dock.

Pickett’s orders were to protect Americans from Indians and to resist any British attempts to interfere in disputes between American settlers and the Hudson’s Bay Company personnel. But Pickett stretched his mandate. He posted a proclamation just above the loading dock, declaring the island to be U.S. property, with himself in charge. The document made clear that “no laws, other than those of the United States nor courts, except such as are held by virtue of said laws” would be recognized.

Strong words for someone whose flimsy camp was in easy range of naval guns. Sure enough, by the end of the very day on which Pickett posted the proclamation, the first guns arrived—21 of them, mounted on the deck of the British warship HMS Satellite. Acting in the absence of the Royal Navy’s commander of the Pacific, R. L. Baynes, who was making rounds in Chile, Douglas quickly sent two more British ships, including the HMS Tribune, to San JuanIsland, with orders to prevent any American reinforcements from landing.

For more than a week, American and British troops stared at each other across the water. The Tribune’s captain, Geoffrey Phipps Hornby, warned Pickett that if he did not immediately abandon his position, or at least agree to a joint occupation of the island, he risked an armed confrontation. According to one witness, Pickett retorted that, if pushed, he would “make a Bunker Hill of it,” fighting to the last man.

Privately, Pickett was less confident. In an August 3 letter to Alfred Pleasanton, adjutant to Harney, who had by then returned to FortVancouver, Pickett noted that if the British chose to land, the Americans would be “merely a mouthful” for them. “I must ask that an express [directions] be sent to me immediately on my future guidance,” he wrote. “I do not think there are any moments to waste.”

Captain Hornby relayed Douglas’ threats to Pickett throughout July and August, but fearing an outbreak of a larger war, he refused to follow the governor’s order to land his Royal Marines and jointly occupy the island. (Although nominally under the civilian Douglas’ command, Hornby had to answer directly to Admiral Baynes, and British Royal Navy officers at the time had wide discretion in deciding whether to initiate hostilities.) Hornby’s gamble paid off. “Tut, tut, no, no, the damn fools,” Baynes reportedly said of Douglas’ order to land troops, when, returning to the area August 5, he at last learned what had been going on in his absence.

In the meantime, the American detachment had managed to fortify its camp with men, artillery and supplies. By late August, the Americans counted 15 officers and 424 enlisted men, still vastly outnumbered by the British but now in a position to inflict significant damage on Hornby’s five ships and the nearly 2,000 men who manned them.

In those days before transcontinental telegraphs and railroads, the news of the fracas on the island did not reach Washington and London until September. Neither capital wanted to see the dispute mushroom into armed conflict. Alarmed by Harney’s aggressive occupation, President James Buchanan—who had negotiated the Treaty of Oregon when he was secretary of state—immediately dispatched one of his most gifted diplomats and battlefield generals, Winfield Scott, to resolve the matter.

Scott was familiar with Harney’s hot temper, having been involved in two of the general’s courts-martial. After Scott finally reached the West Coast in late October 1859, he ordered all but a single company of U.S. troops off the island and negotiated a deal with Douglas permitting joint military occupation of the island until boundary surveys were complete. As Scott sailed home in November, all but one of the British warships withdrew. At Scott’s recommendation, Harney was eventually removed from his command.

“Both sides still believed that if San JuanIsland was lost, the balance of power—and so the security of their respective nations—would be imperiled,” Kaufman says. “Still, I strongly doubt that either side wanted bloodshed.”

Within a few months of Scott’s departure, comparable detachments of roughly 100 British and American troops had settled on opposite ends of the island. The English built a cozy outpost, complete with family quarters for the captain and a formal English garden. The American camp, in contrast, was exposed to the wind and in disrepair. Subject to political tensions over the impending Civil War, Pickett’s men were demoralized. “The difficulty of getting their pay and the refusal of merchants to cash treasury Bills makes the American Officers very anxious,” a visiting Anglican bishop wrote in his journal on February 2, 1861. “They say they fully expect next month to be paid. Troops if six months in arrears of pay may disband themselves. ‘Here am I,’ says Captain Pickett, ‘of 18 years standing, having served my Country so long, to be cast adrift!’ ”

On April 17, 1861, Virginia seceded from the Union. Two months later, Pickett resigned his commission and headed home to Virginia to join the Confederacy, where he would make history in what came to be called Pickett’s Charge up Cemetery Ridge in the last fight on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg. (On that day, July 3, 1863, during 50 minutes of combat, some 2,800 of the men charged to Pickett’s care—more than half of his division—were among the 5,675 Confederates killed, captured or wounded. It was a turning point in the Civil War. Pickett survived, only to suffer other defeats at Five Forks, Virginia, and New Berne, North Carolina. Pickett died a failed insurance agent at the age of 50—just 12 years after Gettysburg and 16 years after landing with a few dozen U.S. soldiers to claim San Juan Island.)

Following Pickett’s departure, relations between the two occupying forces continued in relative harmony. It wasn’t until 1872, in a decision by a panel convened by Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm, brought in as an arbiter, that the San Juan Islands were quietly assigned to the United States. The British took their flag, and their flagpole, and sailed home. With that, the upper left corner of the United States was pinned in place.

In his book on the war that did not quite happen, The Pig War: Standoff at Griffin Bay, Mike Vouri writes that the conflict was settled peacefully because experienced military men, who knew the horrors of war firsthand, were given decision-making authority. “Royal Navy Rear Admiral R. Lambert Baynes remembered the War of 1812 when his decks ‘ran with blood;’ Captain Geoffrey Phipps Hornby had seen the hospital ships of the Crimean War; and U.S. Army Lieutenant General Winfield Scott had led men in battle from Lundy’s Lane in the War of 1812 to the assault on Chapultepec Castle in Mexico. These are the men who refused to consider shedding blood over a tiny archipelago, then in the middle of nowhere; warriors with convictions, and most critically, imaginations.”

The overgrown site of Pickett’s makeshift camp on the southern tip of San Juan Island lies less than a mile from Mike Vouri’s office. Like the Coast Salish Indians before them, Pickett and his men had made their temporary home next to a freshwater spring that still bubbles through thick mats of prairie grass. For the 12 years of joint occupation, until 1872, American soldiers cleaned rifles, washed tinware (and clothes and themselves), smoked pipes, pined for sweethearts and drank away their boredom along the spring’s banks, leaving empty bottles, broken dishes and rusted blades where they lay. Every so often an artifact of Pickett’s days—chipped crockery, clay pipes, tarnished buttons or cloudy marbles—turns up, brought to the surface by animals or the water.

Recently, on a windswept bluff, Vouri picked his way through the marshy grass to show a visitor the water’s source. Ashard of blue glass glinted in the sunlight through the lowslung branches of a scraggly bush. Vouri stooped to pick up the shard—the square-bottomed lower third of a bottle, shimmering with blue-green swirls of tinted glass that had begun to deteriorate—sick glass, archaeologists call it. Near the bottom edge of the bottle was an embossed date: November 1858, eight months before Pickett and his men landed on the island.

Vouri’s latest find will join other broken bottles and artifacts discovered here. In a battlefield, of course, the settled dust also entombs spent shells and arrowheads, grapeshot and mine fragments, broken skulls and shattered bones. But in this old “peacefield” on San Juan Island, the relics are mostly buttons and glass.