The Big Mystery Behind the Great Train Robbery May Finally Have Been Solved

Chris Long’s A Tale of Two Thieves examines the largest cash theft of its time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/71/7471fe55-7642-4ca7-8884-4fff30eb744a/traveling_post_office.jpg)

Gordon Goody is the type of gentleman criminal celebrated by George Clooney’s Oceans trilogy. In the early 1960s, Goody was a dashing, well-dressed, seasoned thief who knew how to manipulate authority. At the height of his criminal game, he helped to plan and execute a 15-man heist that resulted in the largest cash theft in international history. Scotland Yard’s ensuing investigation turned the thieves into celebrities for a British public stuck in a post-war recession funk. Authorities apprehended Goody and his team members, but they failed to uncover one important identity: that of the operation’s mastermind, a postal service insider. Nicknamed “The Ulsterman” because of his Irish accent, the informant has gone unnamed for 51 years.

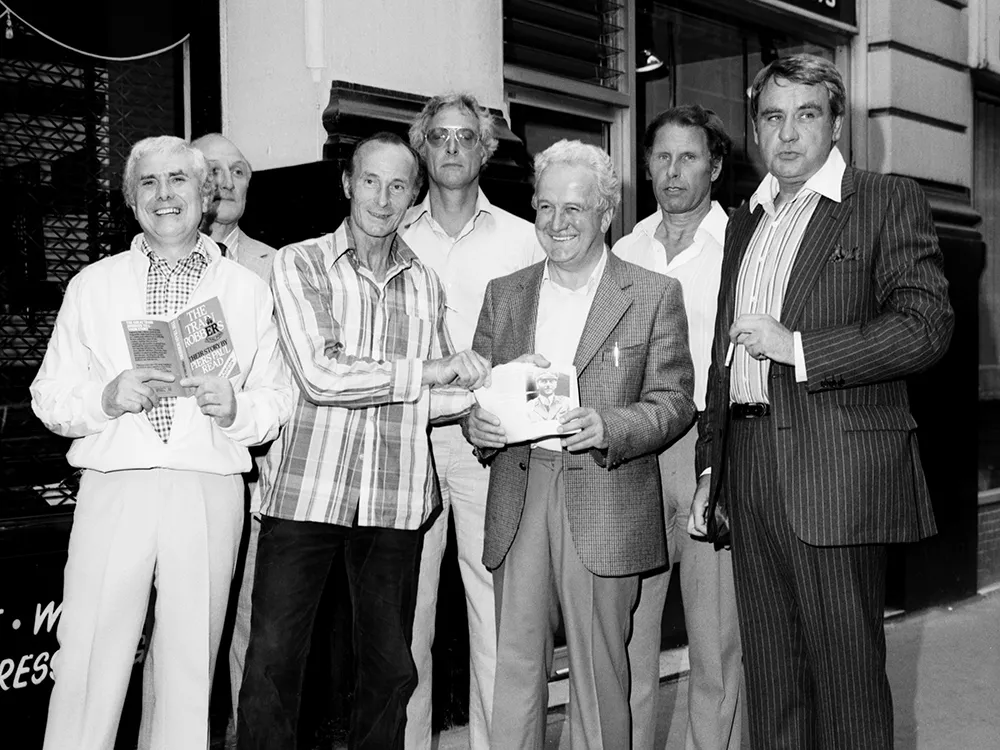

“It was a caper, an absolute caper,” says Chris Long, the director of the upcoming documentary A Tale of Two Thieves. In the film, Gordon Goody, now 84 and living in Spain, reconstructs the crime. He is the only one of three living gang members to know “The Ulsterman’s” name. At the end of the film, Goody confirms this identity – but he does so with hesitation and aplomb, aware that his affirmation betrays a gentleman’s agreement honored for five decades.

----

At 3 a.m. on Thursday, August 8, 1963, a British mail train heading from Glasgow to London slowed for a red signal near the village of Cheddington, about 36 miles northwest of its destination. When co-engineer David Whitby left the lead car to investigate the delay, he saw that an old leather glove covered the light on the signal gantry. Someone had wired it to a cluster of 6-volt batteries and a hand lamp that could activate a light change.

An arm grabbed Whitby from behind.

“If you shout, I will kill you,” a voice said.

Several men wearing knit masks accompanied Whitby onto the conductor’s car, where head engineer Jack Mills put up a fight. An assailant’s crowbar knocked him to the ground. The criminals then detached the first two of the 12 cars on the train, instructing Mills, whose head bled heavily, to drive half a mile further down the track. In the ten cars left behind, 75 postal employees worked, unaware of any problem but a delay.

The bandits handcuffed Whitby and Mills together on the ground.

“For God’s sake,” one told the bound engineers, “don’t speak, because there are some right bastards here.”

In the second car, four postal workers guarded over £2 million in small notes. Because of a bank holiday weekend in Scotland, consumer demand had resulted in a record amount of cash flow; this train carried older bills that were headed out of circulation and into the furnace. Besides the unarmed guards, the only security precaution separating the criminals from the money was a sealed door, accessible only from the inside. The thieves hacked through it with iron tools. Overwhelming the postal workers, they threw 120 mail sacks down an embankment where two Range Rovers and an old military truck awaited.

Fifteen minutes after stopping the train, 15 thieves had escaped with £2.6 million ($7 million then, over $40 million today).

Within the hour, a guard from the back of the train scouted the delay and rushed to the closest station with news of foul play. Alarms rang throughout Cheddington. The police spent a day canvassing farms and houses before contacting Scotland Yard. The metropolitan bureau searched for suspects through a criminal index of files that categorized 4.5 million felons by their crimes, methodologies and physical characteristics. It also dispatched to Cheddington its “Flying Squad,” a team of elite robbery investigators familiar with the criminal underground. Papers reported that in the city and its northern suburbs, “carloads of detectives combed streets and houses,” focusing on the homes of those “named by underworld informants” and also on “the girlfriends of London crooks.”

The New York Times called the crime a “British Western” and compared it to the darings of the Jesse James and the Dalton Brothers gangs. British papers criticized the absence of a national police force, saying that a lack of communication between departments fostered an easier getaway for the lawbreakers. Journalists also balked at the lack of postal security, and suggested that the postal service put armed guards on mail trains.

“The last thing we want is shooting matches on British railways,” said the Postmaster General.

The police knew that the crime required the assistance of an insider with a detailed working knowledge of postal and train operations: someone who would have anticipated the lack of security measures, the amount of money, the location of the car carrying the money, and the right place to stop the train.

The postal service had recently added alarms to a few of its mail cars, but these particular carriages weren’t in service during the robbery. Detective Superintendent G. E. McArthur said the robbers would have known this. “We are fighting here a gang that has obviously been well organized.”

All 15 of the robbers would be arrested, but the insider would remain free. For his role in planning the robbery, the Ulsterman received a cut (the thieves split the majority of the money equally) and remained anonymous but to three people for decades. Only one of those three is still alive.

---

Director Chris Long says that Gordon Goody has a “1950s view of crime” that makes talking to him “like warming your hands by a fire.” Goody describes himself at the start of the film as “just an ordinary thief.” He recounts the details of his criminal past – including his mistakes -- with a grandfatherly matter-of-factness. “Characters like him don’t exist anymore,” continued Long. “You’re looking at walking history.” While his fellow train gang members Bruce Reynolds and Ronnie Biggs later looked to profit from their criminal histories by writing autobiographies, Gordon Goody moved to Spain to live a quiet life and “shunned the public,” in Long’s words.

The producers trusted Goody’s information the more that they worked with him. But they also recognized that their documentary centered on a con artist’s narrative. Simple research could verify most of Goody’s details, but not the Ulsterman’s real name; it was so common in Ireland that Long and Howley hired two private investigators to search through post office archives and the histories of hundreds of Irishmen who shared a similar age and name.

----

Scotland Yard reached a breakthrough in their case on August 13, 1963, when a herdsman told police to investigate Leatherslade Farm, a property about 20 miles away from the crime. The man had grown suspicious over increased traffic around the farmhouse. When police arrived, they found 20 empty mailbags on the ground near a 3-foot hole and a shovel. The getaway vehicles were covered nearby. Inside the house, food filled kitchen shelves. The robbers had wiped away many fingerprints, but police lifted some from a Monopoly game board and a ketchup bottle. One week later, police apprehended a florist named Roger Cordrey in Bournemouth. Over the next two weeks, tips led to the arrests of Cordrey’s accomplices.

By January of 1964, authorities had enough evidence to try 12 of the criminals. Justice Edmund Davies charged the all-male jury to ignore the notoriety that the robbers had garnered in the press.

“Let us clear out of the way any romantic notions of daredevilry,” he said. “This is nothing less than a sordid crime of violence inspired by vast greed.”

On March 26, the jury convicted the men on charges ranging from robbery and conspiracy to obstruction of justice. The judge delivered his sentence a few weeks later. “It would be an affront if you were to be at liberty in the near future to enjoy these ill-gotten gains,” he said. Eleven of the 12 received harsh sentences of 20 to 30 years. The prisoners immediately started the appeals process.

Within five years of the crime, authorities had incarcerated the three men who had evaded arrest during the initial investigation – Bruce Reynolds, Ronald “Buster” Edwards, and James White. But by the time the last of these fugitives arrived in jail, two of the robbers had escaped. Police had anticipated one of these prison breaks. They had considered Charles F. Wilson, a bookmaker dubbed “the silent man,” a security risk after learning that the London underground had formed “an escape committee” to free him. In August of 1964, Wilson’s associates helped him break out of the Winson Green Prison near Birmingham and flee to Canada, where Scotland Yard located and re-arrested him four years later.

Ronnie Biggs became the criminal face of the operation after escaping from a London prison in 1965. On one July night, he made his getaway by scaling a wall and jumping into a hole cut into the top of a furniture truck. Biggs fled to Paris, then Australia before arriving in Brazil in the early 1970s. He lived there until 2001, when he returned to Britain to seek medical treatment for poor health. Authorities arrested him, but after Biggs caught pneumonia and suffered strokes in jail, he received “compassionate leave” in 2009. He died at the age of 84 this past December.

Police recovered approximately 10% of the money, although by 1971, when decimalisation led to a change in UK currency, most of the cash that the robbers had stolen was no longer legal tender.

---

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the Great Train Robbery, inviting the type of publicity that Gordon Goody chose to spend his life avoiding. One reason that he shares his story now, says Chris Long, is that he has become “sick of hearing preposterous things about the crime.” In addition to recounting his narrative, Goody agreed to give the filmmakers the Ulsterman’s name because he assumed the informant had died --- the man had appeared middle-aged in 1963.

At the end of A Tale of Two Thieves, Goody is presented with the Ulsterman’s picture and basic information about his life (he died years ago). Asked if he is looking at the mastermind of the Great Train Robbery, Goody stares at the photo, winces, and shifts in his seat. There is a look of disbelief on his face, as if he is trying to understand how he himself got caught in an act.

Goody shakes his head. “I’ve lived with the guy very vaguely in my head for 50 years.”

The face doesn’t look unfamiliar. Gordon Goody’s struggle to confirm the identity reveals his discomfort with the concrete evidence before him, and perhaps with his effort to reconcile his commitment to the project with a promise he made to himself decades ago. Goody could either keep “The Ulsterman” in the abstract as a legendary disappearing act, or give him a name, and thereby identify a one-time accomplice.

He says yes.