The Beloved Classic Novel “The Little Prince” Turns 75 Years Old

Written in wartime New York City, the children’s book brings out the small explorer in everyone

:focal(3005x2840:3006x2841)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/80/0280cf9d-8e41-4ee0-9049-b76600742151/le-petit-prince-sketch.jpg)

Though reviewers were initially confused about who, exactly, French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s had written The Little Prince for, readers of all ages embraced the young boy from Asteroid B-612 when it hit stores 75 years ago this week. The highly imaginative novella about a young, intergalactic traveler, spent two weeks on The New York Times’ best-seller list and went through at least three printings by December of that year. Though it only arrived in France after World War II, The Little Prince made it to Poland, Germany and Italy before the decade was up.

Soon, the prince traveled to other media; audiobook vinyls debuted as early as 1954, which progressed to radio and stage plays, and eventually a 1974 film starring Bob Fosse and Gene Wilder. Since then there have been sequels (one by Saint-Exupery’s niece), a theme park in South Korea, a museum in Japan, a French boutique with branded Little Prince merchandise, another film adaptation, and most recently, a translation in the Arabic dialect known as Hassānīya, making the book one of the most widely translated work of all-time.

The plot is both simple yet breathtakingly abstract: After crash-landing in the middle of the Sahara Desert, an unnamed aviator is surprised to come across a young, healthy-looking boy. He learns the boy is a prince of a small planet (on which he is the only human inhabitant), and, after leaving his planet because his friend (a rose) was acting up, he traveled the galaxy meeting people on other planets. The prince relates tale after tale to the pilot, who is sympathetic to the boy’s confusion over “important” adult concerns. In the end, the boy leaves to return to his planet and rejoin his troublesome rose, leaving his new friend with heartfelt memories and a reverence for the way children see the world.

How did Saint-Exupéry, an accomplished aviator and fighter pilot himself, as well as a prolific author, come to write the beloved tale? And considering its setting in French north Africa and other unmistakably French influences, how can it also be, as one museum curator argues, an essential New York story too?

After an unsuccessful university career, a 21-year-old Saint-Exupéry accepted a position as a basic-rank soldier in the French military in 1921. Soon after, officers discovered his flying prowess and he began a lengthy—albeit sporadic—aviation career. As Saint-Exupéry went from flying airplanes, to odd jobs, and back to flying, he was writing fiction for adults. He wrote smash hits such as the award-winning Night Flight. After he crash-landed in the Libyan desert, he composed Wind, Sand and Stars, which earned him more accolades and five months on The New York Times’ best-seller list (as well as inspiration for the narrator in The Little Prince).

Then came the Nazi invasion of Europe and World War II, in which Saint-Exupéry served as a reconnaissance pilot. Following the devastating Battle of France, he escaped his home nation with his wife, Salvadoran writer and artist Consuelo Suncin, to New York City, where they arrived on the very last day of 1940.

His stay was not a happy one. Plagued by health issues, marital strife, the stress of a foreign city and most significantly, profound grief over France's fate in the war, Saint-Exupéry turned to his ethereal little friend for comfort, drafting illustration after illustration, page after page in his many New York residences.

Saint-Exupéry biographer Stacy Schiff wrote of the emotional connection between the expatriate author and his itinerant prince. "The two remain tangled together, twin innocents who fell from the sky," she wrote in a 2000 New York Times article.

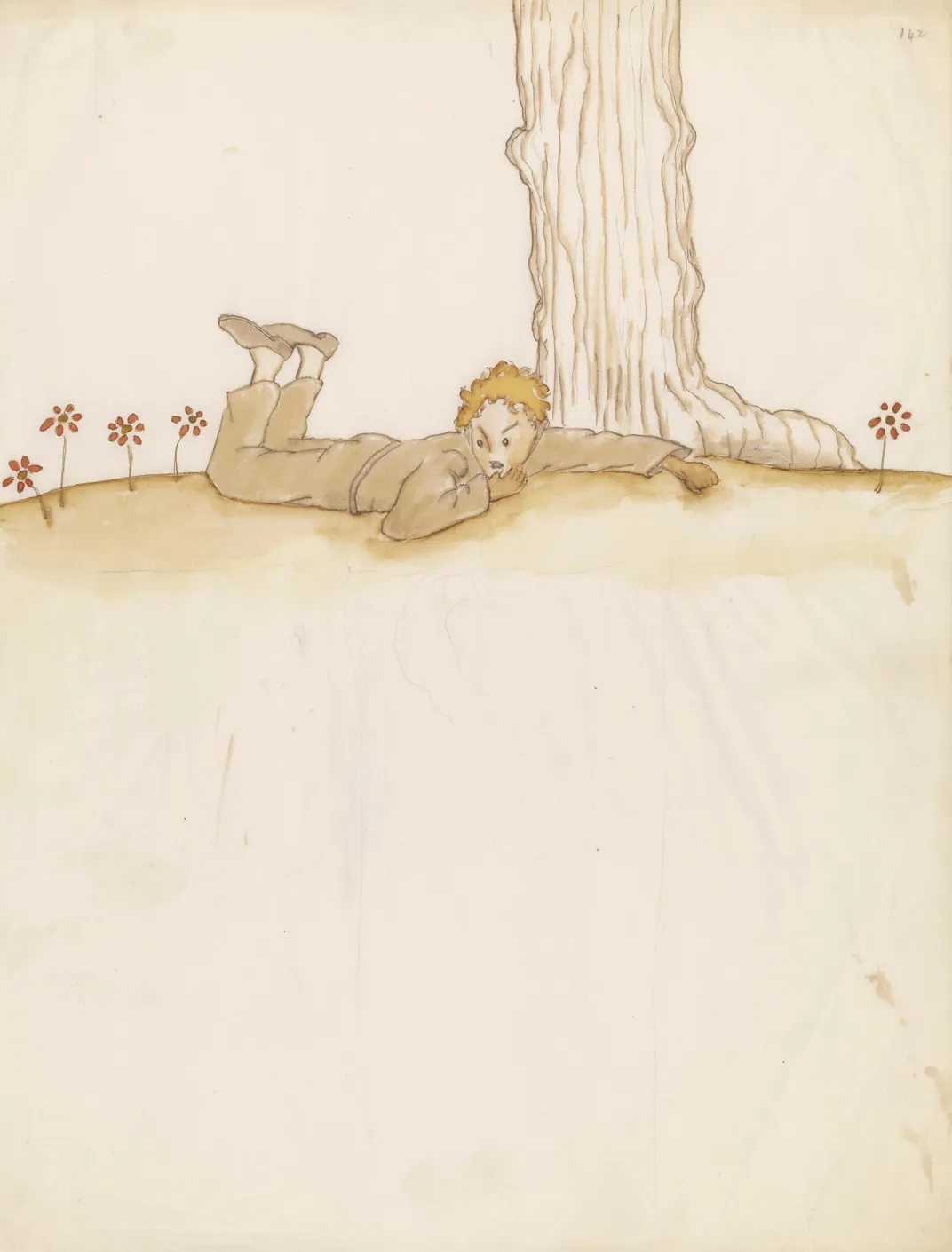

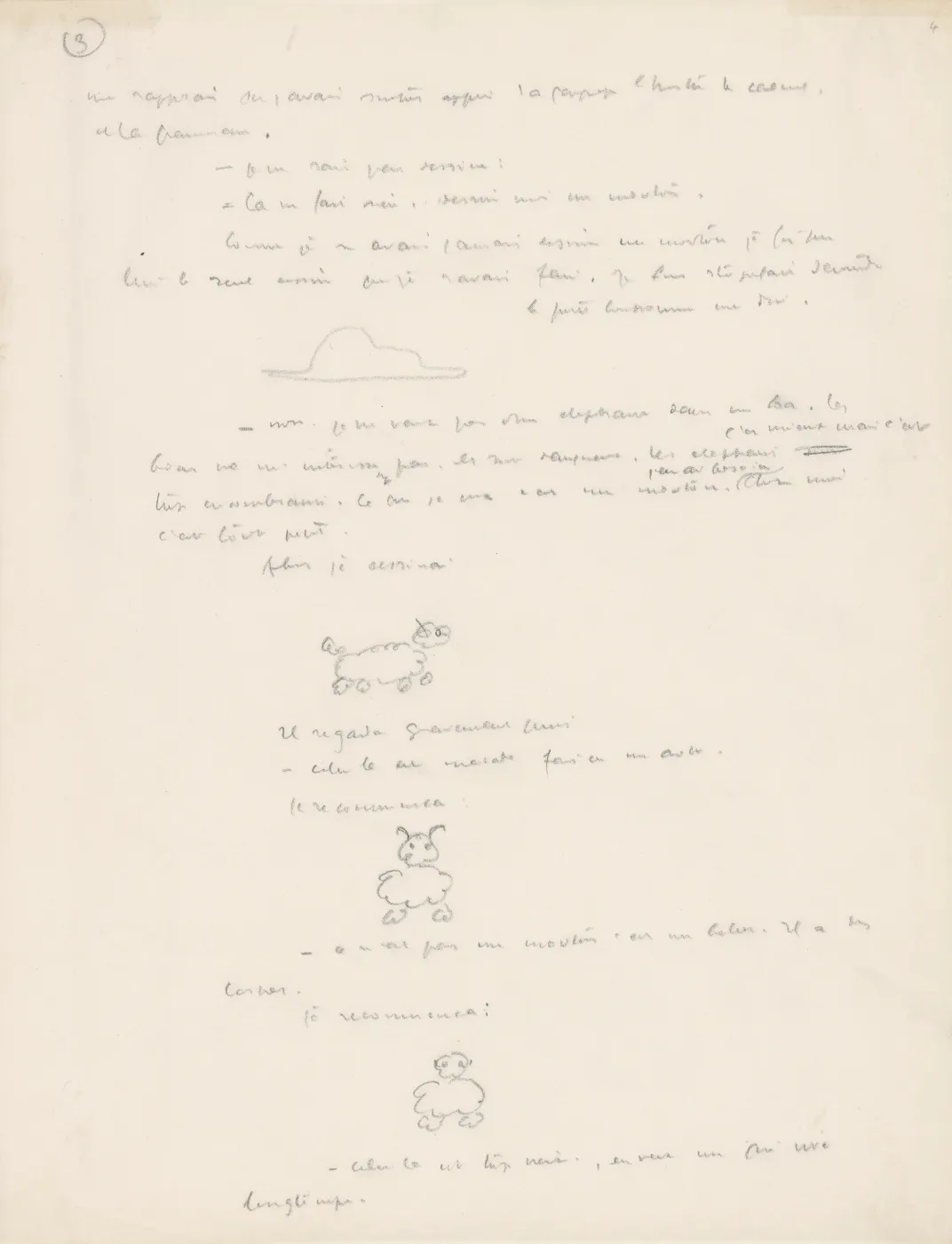

From the beginning, Saint-Exupéry knew his story would feature a desert-stranded narrator and a naive, yet enlightened young prince, but entire chapters and smaller characters came and went before he landed on the 15,000 words that became the first edition of the Le Petit Prince.

"He had a very clear idea of the shape he wanted the story to take and what his tone would be," says Christine Nelson, curator at The Morgan Library & Museum, where the original sketches for the book are held. "He went to great lengths to refine it, but there wasn't a lot of massive rearrangement."

Saint-Exupéry, for example, rewrote and reworked the book’s most indelible line more than 15 times. The phrase "l’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux" ("what is essential is invisible to the eye”), is pronounced by the prince’s earthly fox friend before the prince departs for home—reminding him that truth is only found in what he feels.

"It's a work of inspiration but it's also a work of enormous creative labor," Nelson says. "Of all the pages we have at the Morgan Library, there are probably many more that went into the garbage can."

The 140-page crinkled manuscript acts a looking glass into Saint-Exupéry's time in New York City, as well as the labor of love that bore such an enduring work. Coffee stains, cigarette burns and line after line of crossed-out writing conjure images of a hardworking Saint-Exupéry crouched over a lamp-lit desk, as he often wrote between 11 p.m. and daybreak.

Just as the story hit U.S. bookstores, Saint-Exupéry paid a visit to his closest American friend, journalist Sylvia Hamilton Reinhardt, on his way out of New York. He was bound for Algiers, where he planned to serve again as a French military pilot—a mission from he would not return, famously disappearing on a 1944 reconnaissance flight from Corsica to Germany. "I'd like to give you something splendid," he told Reinhardt as he presented her his original Little Prince manuscript, "but this is all I have." More than two decades later, Reinhardt in turn donated it to the Morgan library.

As Nelson examined the papers and learned more about Saint-Exupéry, she says "the New York context started to feel absolutely essential." In 2014, she led an exhibition at the Morgan titled, "The Little Prince: A New York Story," which detailed Saint-Exupery's extensive New York connections.

For example, Saint-Exupéry’s New York friend Elizabeth Reynal may be the reason for The Little Prince’s existence. The wife of influential publisher Eugene Reynal (whose Reynal & Hitchchock published the story’s first editions) noticed Saint-Exupéry’s drawings and suggested he create a children's book based on them.

Reinhardt also had significant impact. She offered constant advice and visited Saint-Exupéry nearly every night. Many literary scholars believe the story's sage and devoted fox—who teaches the prince to “tame” him, and helps him to discover the value of relationships—was created in her likeness.

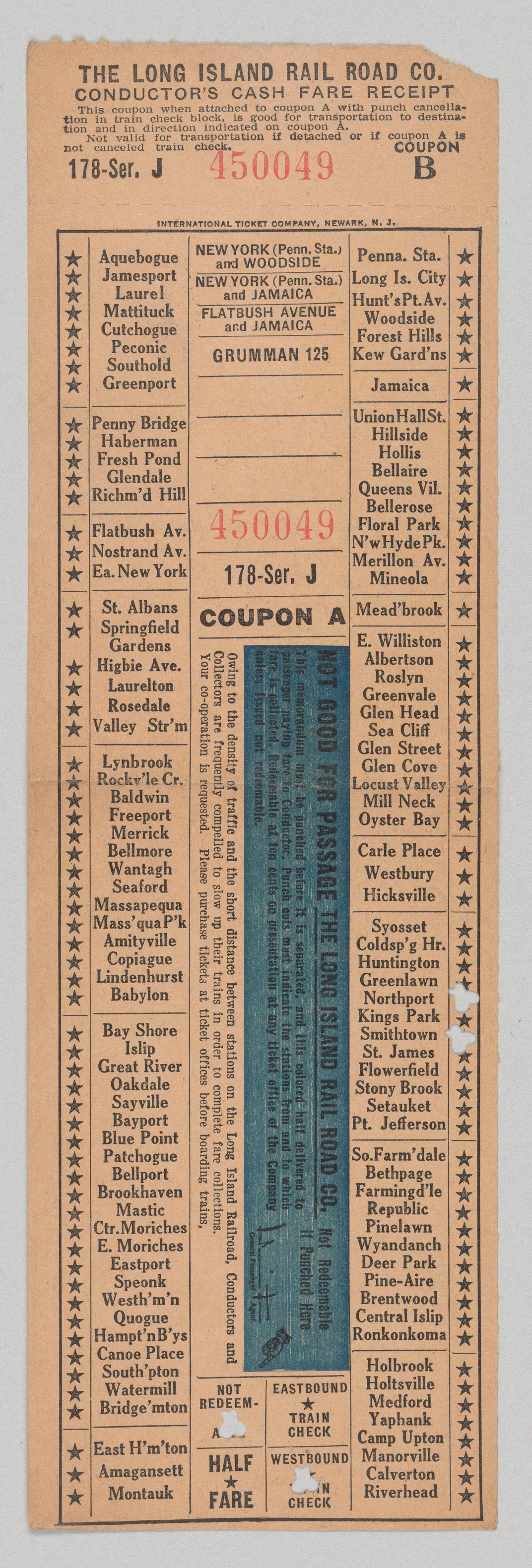

Though it didn’t appear in print, the manuscript suggests that Saint-Exupéry was thinking about New York as he crafted his narrative. On some draft pages, the city appears in references to Rockefeller Center and Long Island.

"In the end, [The Little Prince] became a more universal story because he didn't mention New York," says Nelson.

Recently, the Morgan unexpectedly came across a new set of artifacts that illuminate yet another part of Saint-Exupéry’s experience in writing the book. Joseph Cornell, the renowned collage and assemblage artist, enjoyed a close friendship with Saint-Exupéry during his time in New York. When Cornell’s nephew donated his uncle’s file to the library in 2014, among the train tickets, Hershey's wrappers and, strangely, leaves, were also relics from his friendship with Saint-Exupéry.

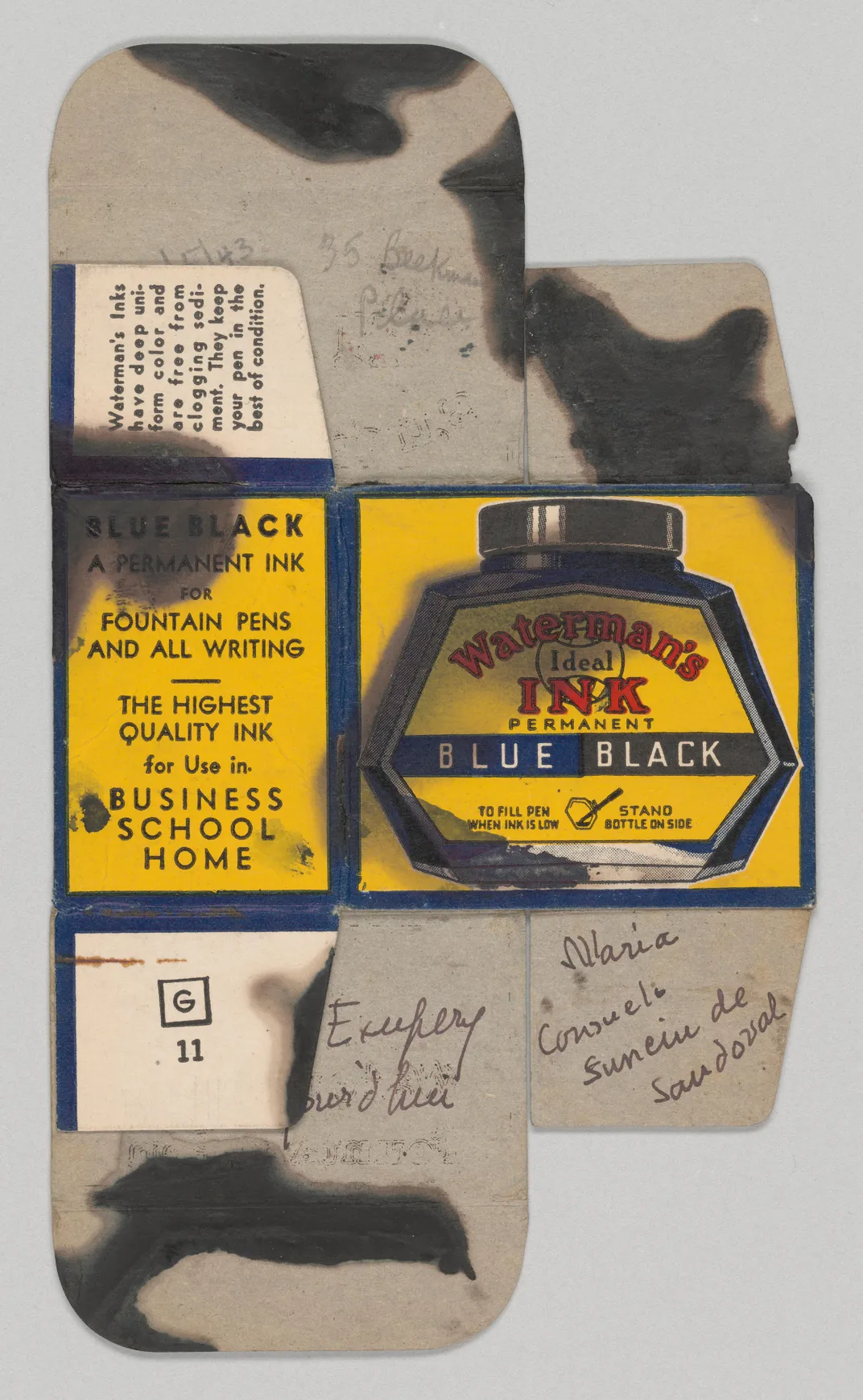

Nelson came across an ink bottle, an 8x10 photograph of the author and his family, and five drawings gifted to Cornell when he visited the author in New York—the exact time when he was creating The Little Prince.

These drawings had never been seen before—besides by Cornell, his family and a lucky LIFE reporter who examined them during an interview with the eccentric artist for a 1967 feature.

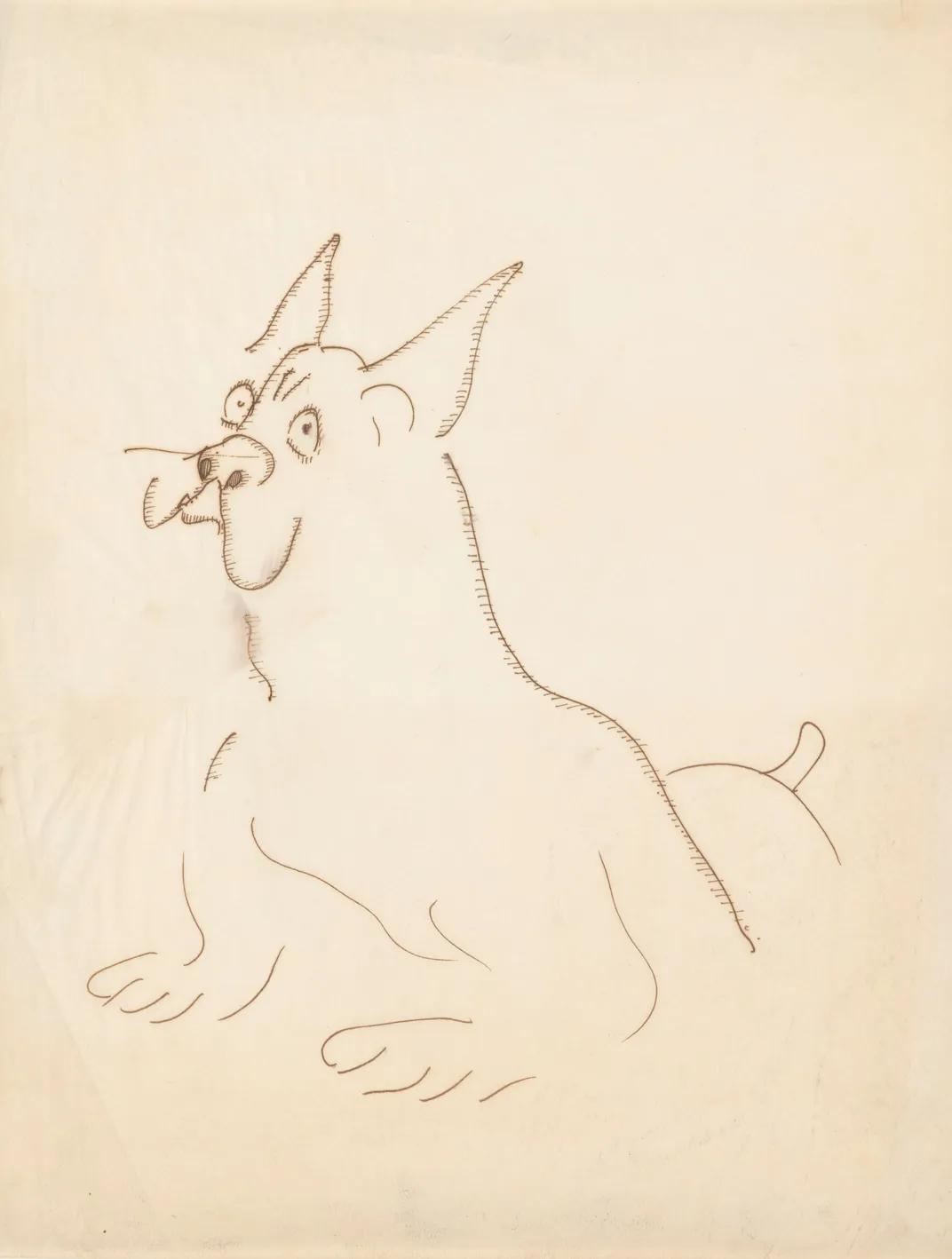

One illustration is clearly of the Little Prince, others feature subjects that never appeared in the novel, like a dog. Though no one can be sure whether these drawings were at some point intended for the story, "they are a part of that moment, and written on the same paper in the same style with the same ink," Nelson says. Some of these items will be on display at The Morgan through June.

"I've been so close to the material, and to see something I knew existed—or had existed at some point—was an intimate and beautiful moment," says Nelson.

This discovery comes at a fitting time. As the world celebrates 75 years with the lessons of love and curiosity that so define The Little Prince, we're reminded that our fascination and universal adoration of Saint-Exupéry's tale will never wane.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/spengler_headshot.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/spengler_headshot.png)