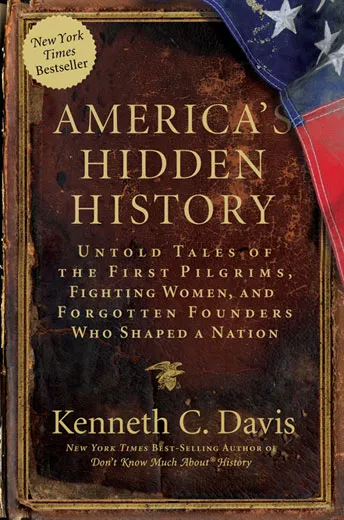

America’s First True “Pilgrims”

An excerpt from Kenneth C. Davis’s new book explains they arrived half a century before the Mayflower reached Plymouth Rock

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/hidden-history-631.jpg)

The first Pilgrims to reach America seeking religious freedom were English and settled in Massachusetts. Right?

Well, not so fast. Some fifty years before the Mayflower left port, a band of French colonists came to the New World. Like the later English Pilgrims, these Protestants were victims of religious wars, raging across France and much of Europe. And like those later Pilgrims, they too wanted religious freedom and the chance for a new life. But they also wanted to attack Spanish treasure ships sailing back from the Americas.Their story is at the heart of the following excerpt from America's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a Nation.

It is a story of America's birth and baptism in a religious bloodbath. A few miles south of St. Augustine sits Fort Mantanzas (the word is Spanish for "slaughters"). Now a national monument, the place reveals the "hidden history" behind America's true "first pilgrims," an episode that speaks volumes about the European arrival in the Americas and the most untidy religious struggles that shaped the nation.

St. Augustine, Florida — September 1565

It was a storm-dark night in late summer as Admiral Pedro Menéndez pressed his army of 500 infantrymen up Florida's Atlantic Coast with a Crusader's fervor. Lashed by hurricane winds and sheets of driving rain, these 16th-century Spanish shock troops slogged through the tropical downpour in their heavy armor, carrying pikes, broadswords and the "harquebus," a primitive, front-loading musket which had been used with devastating effect by the conquistador armies of Cortés and Pizarro in Mexico and Peru. Each man also carried a twelve-pound sack of bread and a bottle of wine.

Guided by friendly Timucuan tribesmen, the Spanish assault force had spent two difficult days negotiating the treacherous 38-mile trek from St. Augustine, their recently established settlement further down the coast. Slowed by knee-deep muck that sucked at their boots, they had been forced to cross rain-swollen rivers, home to the man-eating monsters and flying fish of legend. Wet, tired and miserable, they were far from home in a land that had completely swallowed two previous Spanish armies—conquistadors who themselves had been conquered by tropical diseases, starvation and hostile native warriors.

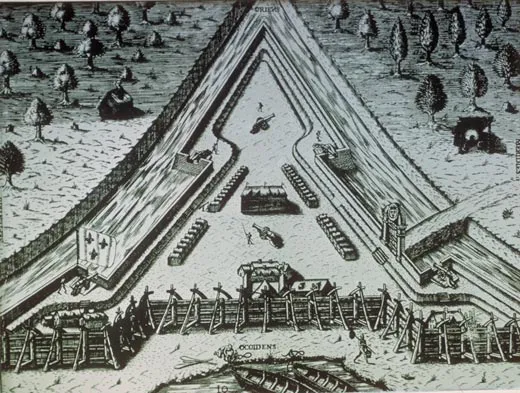

But Admiral Menéndez was undeterred. Far more at home on sea than leading infantry, Admiral Menéndez drove his men with such ferocity because he was gambling—throwing the dice that he could reach the enemy before they struck him. His objective was the French settlement of Fort Caroline, France's first foothold in the Americas, located near present-day Jacksonville, on what the French called the River of May. On this pitch-black night, the small, triangular, wood-palisaded fort was occupied by a few hundred men, women and children. They were France's first colonists in the New World—and the true first "Pilgrims" in America.

Attacking before dawn on September 20, 1565 with the frenzy of holy warriors, the Spanish easily overwhelmed Fort Caroline. With information provided by a French turncoat, the battle-tested Spanish soldiers used ladders to quickly mount the fort's wooden walls. Inside the settlement, the sleeping Frenchmen—most of them farmers or laborers rather than soldiers—were caught off-guard, convinced that no attack could possibly come in the midst of such a terrible storm. But they had fatally miscalculated. The veteran Spanish harquebusiers swept in on the nightshirted and naked Frenchmen who leapt from their beds and grabbed futilely for weapons. Their attempts to mount any real defense were hopeless. The battle lasted less than an hour.

Although some of the French defenders managed to escape the carnage, 132 soldiers and civilians were killed in the fighting in the small fort. The Spanish suffered no losses and only a single man was wounded. The forty or so French survivors fortunate enough to reach the safety of some boats anchored nearby, watched helplessly as Spanish soldiers flicked the eyeballs of the French dead with the points of their daggers. The shaken survivors then scuttled one of their boats and sailed the other two back to France.

The handful of Fort Caroline's defenders who were not lucky enough to escape were quickly rounded up by the Spanish. About fifty women and children were also taken captive, later to be shipped to Puerto Rico. The men were hung without hesitation. Above the dead men, the victorious Admiral Menéndez placed a sign reading, "I do this, not as to Frenchmen, but as to Lutherans." Renaming the captured French settlement San Mateo (St. Matthew) and its river San Juan (St. John's), Menéndez later reported to Spain's King Philip II that he had taken care of the "evil Lutheran sect."

Victims of the political and religious wars raging across Europe, the ill-fated inhabitants of Fort Caroline were not "Lutherans" at all. For the most part, they were Huguenots, French Protestants who followed the teachings of John Calvin, the French-born Protestant theologian. Having built and settled Fort Caroline more than a year earlier, these French colonists had been left all but defenseless by the questionable decision of one of their leaders, Jean Ribault. An experienced sea captain, Ribault had sailed off from Fort Caroline a few days earlier with between five and six hundred men aboard his flagship, the Trinité, and three other galleons. Against the advice of René de Laudonniére, his fellow commander at Fort Caroline, Ribault planned to strike the new Spanish settlement before the recently arrived Spanish could establish their defenses. Unfortunately for Ribault and his shipmates, as well as those left behind at Fort Caroline, the hurricane that slowed Admiral Menéndez and his army also ripped into the small French flotilla, scattering and grounding most of the ships, sending hundreds of men to their deaths. According to René de Laudonniére, it was, "the worst weather ever seen on this coast."

Unaware that Fort Caroline had fallen, groups of French survivors of the storm-savaged fleet came ashore near present-day Daytona Beach and Cape Canaveral. Trudging north, they were spotted by Indians who alerted Menéndez. The bedraggled Frenchmen were met and captured by Spanish troops at a coastal inlet about 17 miles south of St. Augustine on September 29, 1565.

Expecting to be imprisoned or perhaps ransomed, the exhausted and hungry Frenchmen surrendered without a fight. They were ferried across the inlet to a group of dunes where they were fed what proved to be a last meal. At the Admiral's orders, between 111 and 200 of the French captives—documents differ on the exact number—were put to death. In his own report to King Philip, Admiral Menéndez wrote matter-of-factly, if not proudly, "I caused their hands to be tied behind them, and put them to the knife." Sixteen of the company were allowed to live—self-professed Catholics who were spared at the behest of the priest, who reported, "All the rest died for being Lutherans and against our Holy Catholic Faith."

Twelve days later, on October 11, the remaining French survivors, including Captain Jean Ribault, whose Trinité had been beached further south, straggled north to the same inlet. Met by Menéndez and ignorant of their countrymen's fates, they too surrendered to the Spanish. A handful escaped in the night, but on the next morning, 134 more French captives were ferried across the same inlet and executed; once again, approximately a dozen were spared. Those who escaped death had either professed to be Catholic, hastily agreed to convert or possessed some skills that Admiral Menéndez thought might be useful in settling St. Augustine—the first permanent European settlement in the future United States, born and baptized in a religious bloodbath.

Although Jean Ribault offered Menéndez a large ransom to secure his safe return to France, the Spanish Admiral refused. Ribault suffered the same fate as his men. Following Ribault's execution, the French leader's beard and a piece of his skin were sent to King Philip II. His head was cut into four parts, set on pikes and displayed in St. Augustine. Reporting back to King Philip II, Admiral Menéndez wrote, "I think it great good fortune that this man be dead, for the King of France could accomplish more with him and fifty thousand ducats than with other men and five hundred thousand ducats; and he could do more in one year, than another in ten . . . ."

Just south of modern St. Augustine, hidden off the well-worn tourist path of t-shirt stands, sprawling condos and beach-front hotels, stands a rather inconspicuous National Monument called Fort Matanzas. Accessible by a short ferry ride across a small river, it was built by the Spanish in 1742 to protect St. Augustine from surprise attack. Fort Matanzas is more a large guardhouse than full-fledged fort. The modest structure, about fifty feet long on each side, was constructed of coquina, a local stone formed from clam shells and quarried from a nearby island. Tourists who come across the simple tower certainly find it far less impressive than the formidable Castillo de San Marco, the star-shaped citadel that dominates St. Augustine's historic downtown.

Unlike other Spanish sites in Florida named for Catholic saints or holy days, the fort's name comes from the Spanish word, matanzas, for "killings" or "slaughters." Fort Matanzas stands near the site of the grim massacre of the few hundred luckless French soldiers in an undeclared war of religious animosity. This largely unremarked atrocity from America's distant past was one small piece of the much larger struggle for the future of North America among contending European powers.

The notion of Spaniards fighting Frenchmen in Florida four decades before England established its first permanent settlement in America, and half a century before the Pilgrims sailed, is an unexpected notion to those accustomed to the familiar legends of Jamestown and Plymouth. The fact that these first settlers were Huguenots dispatched to establish a colony in America in 1564, and motivated by the same sort of religious persecution that later drove the Pilgrims from England, may be equally surprising. That the mass execution of hundreds of French Protestants by Spanish Catholics could be mostly overlooked may be more surprising still. But this salient story speaks volumes about the rapacious quest for new territory and brutal religious warfare that characterized the European arrival in the future America.

Excerpted from America's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a Nation, by Kenneth C. Davis. Copyright(c) 2008 by Kenneth C. Davis. By permission of Smithsonian Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.