A Mobile Phone From 1922? Not Quite

History often plays linguistic tricks on us, especially when it comes to rapidly changing technologies

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120117015058eves-wireless-470x251.jpg)

I recently came across a short, silent film from 1922 called Eve’s Wireless. Distributed by the British Pathe company, the film supposedly shows two women using a wireless phone. Apparently this video has been making the rounds for the past few years. Could it be an early demonstration of some futuristic technology? I hate to be the Internet’s wet blanket, but no. It’s not a mobile phone.

Rather than an early mobile phone, think of the box they’re holding as an early Walkman; because the two women on the street don’t have a telephone, but rather a crystal radio. The confusion comes from the fact that the term “wireless telephone” was widely used in 1922 for what we simply call “radio” today.

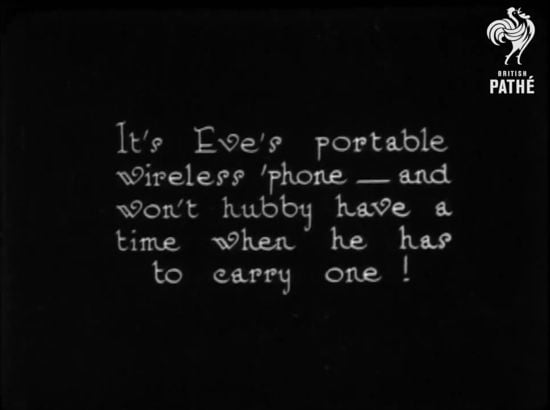

The film opens with two women walking down the street with an umbrella and a radio in a box. An inter-title slate (the words that would appear in a silent movie to help aid in narrative development and were sometimes known as “letter cards”) explains that “It’s Eve’s portable wireless ‘phone — and won’t hubby have a time when he has to carry one!”

In the next shot the women approach a fire hydrant and attach a ground wire from the radio to the hydrant. Crystal radios don’t need a power source (like a battery) because they derive their power from a long antenna, which Eve has strung up through an umbrella.

After they get the umbrella up, one of the women puts a small speaker up to her ear. The film then cuts to a shot of a woman speaking into a microphone.

She then holds that microphone up to a phonograph, which is presumably playing music.

Since the woman on the street only has a speaker to her ear and no microphone, it’s reasonable to assume that our Jazz Age disc jockey can’t hear her talking to her friend. What’s not entirely clear from the film is whether the woman playing the phonograph is playing it for many people or just the two women on the snowy street. The use of the word “telephone” in 1922 didn’t necessarily mean two devices that could both receive and transmit messages. Sometimes (as possibly was the case with Eve’s Wireless) the telephone was used for a one-way message.

You can watch the entire film for yourself.

The use of an umbrella as an antenna for a crystal radio dates back at least to 1910, as we can see from the image below, which ran in the February 20, 1910 Washington Post. The image is pretty amazing to 21st century eyes, but it’s not until we read the last few lines of the accompanying article that we realize the wireless communication is only traveling in one direction and is little more than a crystal radio, which needs a ground connection.

Wives can call husbands at their offices or on the way to Harlem or the suburbs in the car and say, “Do stop at the butcher’s on the corner and get some liver and bacon!” It’s the girl’s day out. And you know how she is! She never orders a thing ahead….

Advice to Married Men – Don’t you care when your wife says angrily, “Don’t tell me, I know you heard me. I called you all day and your wireless telephone was in perfect condition when you fastened it to your hat this morning when you left the house.”

Affect a look of surprise and reply, “Don’t be angry dear. I forgot to take off my rubbers and wore them all day.”

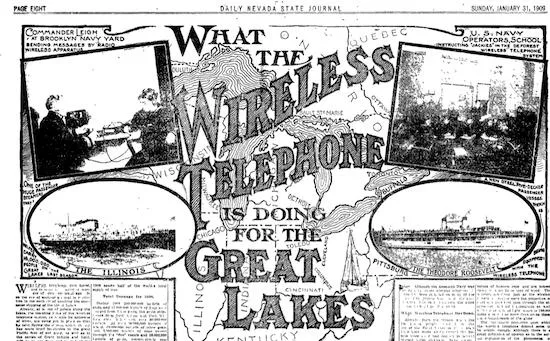

Indeed, by 1922, the term “wireless telephone” as used in Eve’s Wireless was actually quite old fashioned. The article below from the January 31, 1909 Nevada State Journal also shows an early use of the term for point-to-point radio communication with ships on the Great Lakes.

An article in the May, 1922 issue of Radio Broadcast magazine even mentions the shift in terminology in an article called “The Romance of the Radio Telephone.”:

The story of the radio telephone is a study of extremes. It is the most popular fad at this moment, yet only a short while ago it was the most unpopular invention ever introduced to the public. To-day it is in many good hands for full and sound exploitation; a dozen years ago the wireless telephone, as it was then called, was the prey of unscrupulous stock promoters who used it as a means of prying money away from the gullible public.

Flip through the pages of an early radio magazine like Radio Broadcast published before June of 1922 and you’ll come across countless uses of the term “wireless telephone.” But by the July, 1922 issue almost every article and advertisement in Radio Broadcast had stopped using the term. This was no accident.

The U.S. Commerce Department held a meeting in 1922 to standardize the technical language of radio. At that meeting the Committee on Nomenclature of the Radio Telephone Conference defined terms like “interference” and “antenna.” The Committee also recommended the adoption of the word “radio” rather than “wireless.”

The June, 1922 issue of Radio Broadcast magazine devoted a page to explaining the committee’s recommendations with the headline, “What to Call Them.” The first recommendation on the list was about the use of the word “radio”:

In place of the word “Wireless” and names derived from it, use the prefix “Radio”; Radio Telegraphy, Radio Telephony

In 1922, the language of radio was in transition because of radical technological improvements made by men like Lee de Forest and Edwin Howard Armstrong over the previous twenty years. The concept of broadcasting (transmitting from one transmitter to many receivers) was technically impractical until the mid-1910s, when Armstrong improved vacuum tube technology, making it possible to amplify a radio signal thousands of times more than was capable before. During World War I, the U.S. government commandeered all wireless transmitters, which kept Armstrong’s technology from being used by anyone but the military. But after the war, the practical uses of radio as a form of mass media started to be realized.

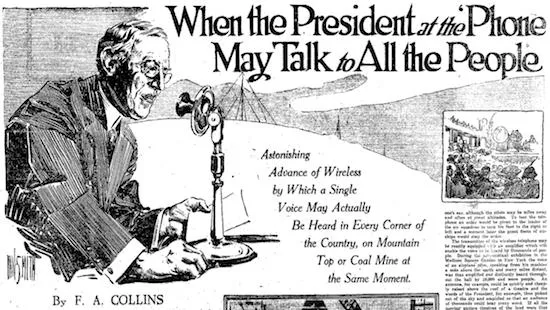

The article below appeared in the June 15, 1919 Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette and describes the advances that were just over the horizon; a futuristic time when the president might address the entire nation simultaneously over the radio. The president “at the ‘phone” as it were:

The terms “wireless telegraphy” and “wireless telephone” were kind of like calling the automobile a “horseless carriage.” Telephones and electric telegraphs in the early 1900s depended on physical lines that would transmit voices and electrical impulses from one person to another. An article by Prof. J. H. Morecroft in the July, 1922 issue of Radio Broadcast magazine explains why the transition was made from using the term “wireless” to the term “radio.”

The new idea of using radiated energy, as contrasted to the previous schemes, gives us the reason for the change of name from wireless telegraphy, up to now a proper name for the art, to that of radio communication, indicating that the power used in carrying the message was not due to conduction through the earth’s surface, or to magnetic induction, but to energy which was actually shaken free from the transmitting station antenna, and left to travel freely in all directions.

In 1922 telephones were hard-wired and your voice was carried over lines that would have to go to an operator. The operator would then patch you in with another physical wire to the desired recipient of your call.

British Pathe even referred to the supposed mobile phone in Eve’s Wireless as the first “flip phone” because the top of the radio receiver opened.

But as you can see from the photos and advertisement below, this was a popular design for crystal radios in the early 1920s.

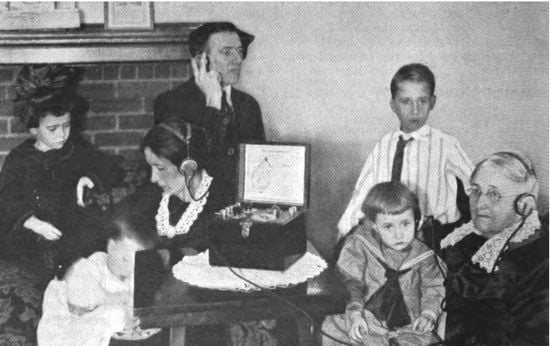

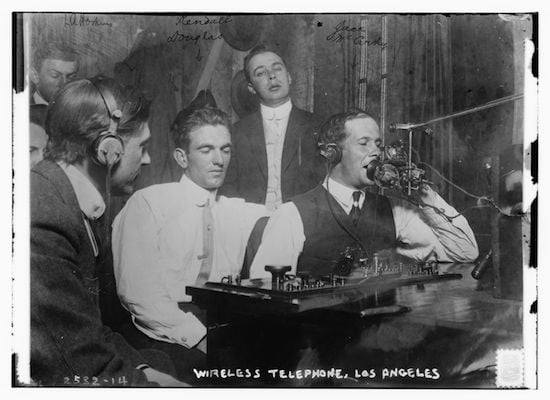

Below are photographs from the Library of Congress which date from between 1910 and 1915. The handwritten description on the bottom reads, “Wireless Telephone, Los Angeles.”

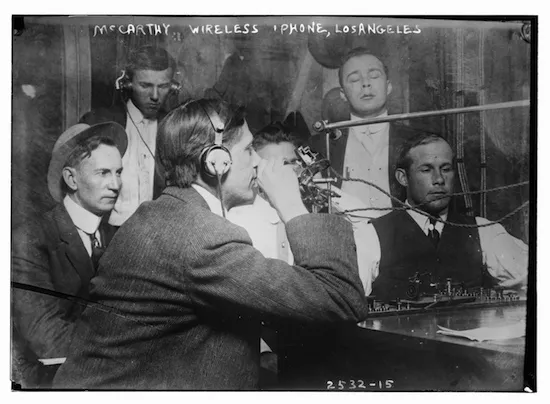

You’ll notice that in the picture below it says “McCarthy Wireless ‘phone,” not “iPhone,” as my 21st century brain initially read it:

History often plays linguistic tricks on us. We all look back at earlier eras through the prism of our own biases. The evolution of language — especially when it comes to rapidly changing technologies — can make us think we’re watching or reading about something much more incredible than it is. However, there was a lot of exciting futuristic communications technologies that people were devising at the beginning of the radio age, and we’ll look at a few of those in the weeks to come.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)