A Halloween Massacre at the White House

In the fall of 1975 President Gerald Ford survived two assassination attempts and a car accident. Then his life got really complicated

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Halloween-Massacre-White-House-631.jpg)

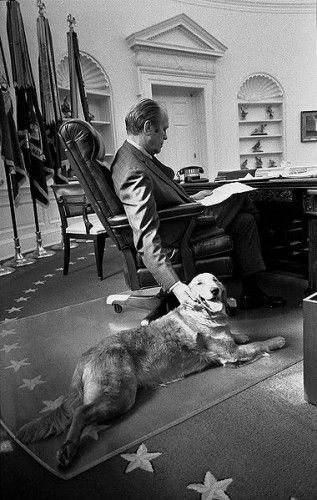

In the fall of 1975, President Gerald Ford was finding trouble wherever he turned. He’d been in office just over a year, but he remained “acutely aware” that he was the only person in U.S. history to become the chief executive without being elected. His pardon of Richard Nixon, whose resignation after the Watergate scandal had put Ford in the White House, was still controversial. Democratic voters had turned out in droves in the congressional midterm elections, taking 49 seats from the Republicans and significantly increasing their party’s majority in the House. Now the presidential election was just a year away, and popular California Governor Ronald Reagan was poised to challenge Ford for the GOP nomination.

But his political troubles were only the beginning. On September 5, 1975, Ford spoke at the California state capitol in Sacramento. He was walking toward a crowd in a park across the street when a woman in a red robe stepped forward and pointed a Colt semi-automatic pistol at him. Secret Service Agent Larry Buendorf spotted the gun, leaped in front of Ford and wrestled Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, a member of the Charles Manson family, to the ground before she could fire.

On September 22, Ford was at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco when a five-time divorcee named Sara Jane Moore fired a .38 caliber revolver at him from across the street. Her shot missed the president’s head by several feet before Oliver Sipple, a former Marine standing in the crowd, tackled her.

And on the evening of October 14, Ford’s motorcade was in Hartford, Connecticut, when a 19-year-old named James Salamites accidentally smashed his lime-green 1968 Buick into the president’s armored limousine. Ford was uninjured but shaken. The car wreck was emblematic of the chaos he was facing.

Back in Washington, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller represented a problem. Ford had appointed him in August of 1974 mainly because the former governor of New York was seen to be free from any connections to Watergate. The president had assured Rockefeller that he would be a “full partner” in his administration, particularly in domestic policy, but from the start, the White House chief of staff, Donald Rumsfeld, and his deputy Dick Cheney worked to neutralize the man they viewed as a New Deal economic liberal. They isolated him to the point where Rockefeller, when asked what he was allowed to do as vice president, said, “I go to funerals. I go to earthquakes.” Redesigning the vice presidential seal, he said, was “the most important thing I’ve done.”

With the 1976 election looming, there were grumblings from the more conservative Ford staffers that Rockefeller was too old and too liberal, that he was a “commuting” vice president who was more at home in New York, that Southerners would not support a ticket with him on it in the primaries, especially against Reagan. To shore up support on the right, Rumsfeld and Cheney, who had already edged out some of the president’s old aides, helped to persuade Ford to dump Rockefeller.

On October 28, Ford met with Rockefeller and made it clear that he wanted the vice president to remove himself from the ticket. “I didn’t take myself off the ticket,” Rockefeller would later tell friends. “He asked me to do it.” The next day, Ford gave a speech denying federal aid to spare the City of New York from bankruptcy—aid Rockefeller had lobbied for. The decision—immortalized in the New York Daily News headline, “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD”—was yet another indication of Rockefeller’s waning influence. In haste and some anger, he wrote Ford a letter saying he was withdrawing as a candidate for vice president.

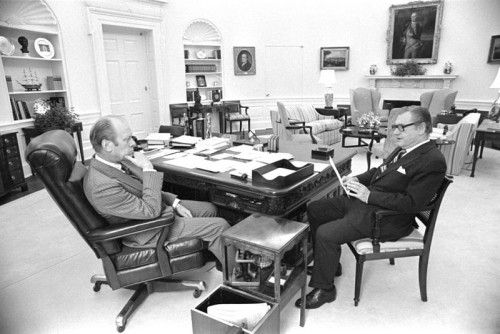

That wasn’t the only shakeup within Ford’s administration. Bryce Harlow, a former Nixon adviser, lobbyist and outside adviser to the president, noted the appearance of “internal anarchy” among the Nixon holdovers at the White House and the cabinet, particularly among Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and CIA Director William Colby. Kissinger was particularly incensed over Colby’s testimony in congressional hearings on CIA activities. “Every time Bill Colby gets near Capitol Hill, the damn fool feels an irresistible urge to confess to some horrible crime,” Kissinger snarled.

Harlow met with Ford’s White House staff, known to Kissinger as the “kitchen cabinet,” and the problem was quickly apparent to him, too. He advised Ford, “You have to fire them all.”

In what became known as the Halloween Massacre, Ford nearly did just that. On November 3, 1975, the president announced that Rockefeller had withdrawn from the ticket and that George H.W. Bush had replaced William Colby as director of the CIA. Schlesinger, too, was out, to be replaced by Rumsfeld. Kissinger would remain secretary of state, but Brent Scowcroft would replace him as national security adviser. And Cheney would replace Rumsfeld, becoming, at age 34, the youngest chief of staff in White House history.

Ford intended the moves as both a show of independence and a bow to his party’s right wing in advance of his primary fight against Reagan. Though advisors agreed that Kissinger’s outsized role in foreign policy made Ford appear less presidential, many observers viewed the shakeup as a blatant power grab engineered by Rumsfeld.

Rockefeller was one of them. Still vice president, he warned Ford, “Rumsfeld wants to be president of the United States. He has given George Bush the deep six by putting him in the CIA, he has gotten me out.… He was third on your list and now he has gotten rid of two of us.… You are not going to be able to put him on the because he is defense secretary, but he is not going to want anybody who can possibly be elected with you on that ticket.… I have to say I have a serious question about his loyalty to you.”

The Republican presidential primaries were as bruising as predicted, but conservatives were infuriated when Reagan promised to name “liberal” Pennsylvania Senator Richard Schweiker as his running mate in a move designed to attract centrists. Ford won the nomination, narrowly. After Reagan made it clear that he would never accept the vice presidency, Ford selected Kansas Senator Bob Dole as his running mate in 1976, but the sagging economy and the fallout from the Nixon pardon enabled the Democrat, Jimmy Carter, the former Georgia governor, to win a close race.

At the time, Ford said he alone was responsible for the Halloween Massacre. Later, he expressed regret: “I was angry at myself for showing cowardice in not saying to the ultraconservatives, ‘It’s going to be Ford and Rockefeller, whatever the consequences.’ ” And years later, he said, “It was the biggest political mistake of my life. And it was one of the few cowardly things I did in my life.”

Sources

Articles: “Behind the Shake-up: Ford Tightens Grip,” by Godfrey Sperling Jr., Christian Science Monitor, November 4, 1975. “Ford’s Narrowing Base,” by James Reston, New York Times, November 7, 1975. “Enough is Enough” by Tom Braden, Washington Post, November 8. 1975. “A No-Win Position” by Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, Washington Post, November 8, 1975. “Context of ‘November 4, 1975 and After: Halloween Massacre’ Places Rumsfeld, Cheney in Power,” History Commons, http://www.historycommons.org/context.jsp?item=a11041975halloween. “Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, 41st Vice President (1974-1977)” United States Senate, http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Nelson_Rockefeller.htm. “The Long March of Dick Cheney,” by Sidney Blumenthal, Salon, November 24, 2005. “Infamous ‘Drop Dead’ ” Was Never Said by Ford,” by Sam Roberts, New York Times, December 28, 2006.

Books: Timothy J. Sullivan, New York State and the Rise of Modern Conservatism: Redrawing Party Lines, State University of New York Press, Albany, 2009. Jussi Hanhimaki, The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy, Oxford University Press, 2004. Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography, Simon & Schuster, 1992.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)