A 1722 Murder Spurred Native Americans’ Pleas for Justice in Early America

In a new book, historian Nicole Eustace reveals Indigenous calls for meaningful restitution and reconciliation rather than retribution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/7a/9c7a8b84-348b-4a9a-a007-f0f68d9605bd/covered_with_night.jpg)

What constitutes justice after the commission of a heinous act? This question regularly anguishes American communities and indeed the nation. In 1722, the colony of Pennsylvania was roiled by the murder of a Susequehannock hunter at the hands of a pair of colonial traders. Colonial officials promised to extract “the full measure of English justice” and set about apprehending the perpetrators, organizing for a trial and ultimately for punishment, imagining this to be the height of respect and proper procedure. But this English-style process was not what Indigenous communities expected or wanted. Rather, they advocated for and ultimately won, at a treaty in Albany, New York, a process of acknowledgment, restitution and then reconciliation.

The lands in the Pennsylvania colony were part of a larger northeastern Native America that included the Six Nations of the Iroquoian-speaking Haudenosaunee as well as more local tribes like the Susquehannock. Over the years, Indigenous leaders and Pennsylvania officials carefully managed diplomatic relationships both in hopes of maintaining semi-peaceful coexistence despite aggressive colonial settlement, and to facilitate trade.

Sawantaeny had welcomed two prominent settler traders, brothers from Conestago, a community that included both Native Americans and colonists, to his home near the border with Maryland along the Monocacy River. They were negotiating the purchase of furs and skins. But whatever they offered, Sawantaeny had refused it. One of the traders responded by throwing something down. “Thud. The clay pot hits the frozen ground.” One of the traders then struck Sawantaeny with his gun, hard.

He died the next day, inside the cabin he shared with his Shawnee wife, on a bearskin she had prepared. His death set in motion a chain of communication to multiple tribal nations; within weeks the Pennsylvania governor and council sent out emissaries, and within months emissaries from the Haudenosaunee and the Conestoga community, including the man known as Captain Civility, were coming to Philadelphia to try to learn more about what happened and how to proceed.

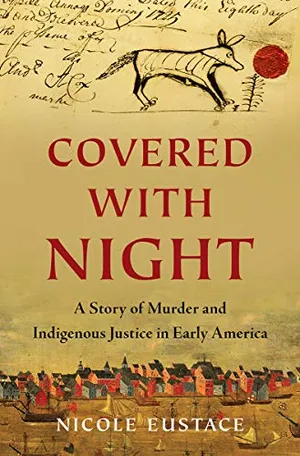

With vivid details and narration, in her new book, Covered With Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America, historian Nicole Eustace tells the story not only of this shocking event, but of a year of communication and miscommunication, false starts and resolution among this diverse group. The Albany “Great Treaty of 1722” included condolence ceremonies and reparation payments as well as the forgiveness of Sawantaeny’s killers. The year that began with a death and ended in a treaty, Eustace says, reveals so much about different ways to define, and then achieve, justice.

Eustace spoke with Smithsonian about the murder and life in 18th-century colonial Pennsylvania for settlers and Native Americans

Covered with Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America

An immersive tale of the killing of a Native American man and its far-reaching implications for the definition of justice from early America to today

The murder you describe occurred in Pennsylvania in early 1722. What was Pennsylvania like, and who lived there?

In 1722, Pennsylvania was Native ground. Only a few thousand colonists lived in the city of Philadelphia. We might imagine founder William Penn’s green country town stretching from river to river with its gridded streets and its well-planned public squares as if it was already there. But in 1722, it was only a few blocks wide, hugging the Delaware River. In the records it is clear that city council members did not even know if there were any roads west of the Schuylkill River, and they did not know where the city limits actually were. Philadelphia’s not a big place even now, but then it was tiny.

The Pennsylvania region at the time was home to a very wide variety of people, some like the Susquehannock have been there for many generations, and others were refugees from different wars that have been happening that all gathered together to rebuild community. Along the Atlantic coast, it’s really Algonquin territory. And then getting into the Great Lakes and the Hudson region is really Iroquoia.

We need to recognize and respect Native sovereignty in this period while not underplaying the sense of menace coming from colonists who were engaging in so many different forms of incursion on Native lands and Native lives. At one of the first meetings that Captain Civility, the Native spokesperson in this case, has with the colonists he says, “Every mouse that rustles the leaves, we’re worried it’s colonists coming on a slaving mission.”

The degree of Native slavery is an incredibly important area of historical inquiry right now. There are leading scholars who have been doing incredible work on the origins of American slavery related to the Atlantic slave trade in people of African origin, but also coming out of colonial Indian wars. And in fact, in places like New England, some of the first laws regulating slavery apply to Native peoples and not to people of African origin at all.

In terms of the immediate crisis surrounding these events, the Yamasee War was centered in South Carolina but rippled throughout the region. Southern colonists were trading for Native slaves in very significant numbers and ultimately placed such a burden on Native peoples that it sparked this widescale conflict in response. So people arrived in the Susquehanna Valley in Pennsylvania fleeing from that trade and that war. And then also feeling pressure from colonists that were trying to get into the Ohio Valley at-large.

How important was trade for colonial-Native interaction and relationships?

Native people in the Pennsylvania region were very sophisticated traders and had been trading with Europeans for over a century. They valued commercial goods just the same way that colonists did. They sometimes used them in different ways or put them to different uses, but they were in the market for a very wide range of goods. European cloth in particular was such a highly desired good that the historian Susan Sleeper-Smith suggests that maybe we shouldn’t call it the fur trade, which is what colonists were trading for. Maybe we should turn it around and call it the cloth trade, which is what Native people were trading for. I really like that equalization of the exchange because the stereotype is the Europeans are getting all these valuable furs and they’re trading it off for trinkets. But the Native peoples are trading for cloth, all kinds of metal goods, glassware, anything from a copper pot to glass stemware to jewelry, metals.

You have a huge cast of characters in this book! Could you tell us about those at center of the terrible events of February, 1722?

So John Cartlidge, one of the most active fur traders in Pennsylvania in this period, lived in a very substantial house, with a store in a Conestoga community in the Susquehanna Valley. It was a polyglot Native community made up of members of a lot of different groups. Some Algonquin, some Iroquoian, all groups that had gathered together to try to rebuild their lives after a period of tremendous instability. It was a fairly peaceful, pluralistic community. John Cartlidge lived in and among these various Native people and he spoke different Algonquin languages, the Delaware tongue in particular. He also is among the best suppliers of furs to traders in Philadelphia.

Sawantaeny was a very successful hunter, a member of the Five Nations Iroquois. His wife, Weynepeeweyta, was a member of the Shawnee. They lived in a cabin near the Monocacy River, an area that even after centuries of colonialism was very rich in game. It’s marked on the map as a place where there were a lot of deer and elk that came to feed and water.

In February of 1722 John goes riding off to Sawantaeny’s cabin with his brother Edmund, two indentured servant lads, and some young Native men, some Shawnee and members of other groups. In picking these Shawnee guides to help them locate Sawantaeny’s home, the Cartlidge brothers were also picking up people with really important linguistic knowledge to help them communicate with Sawantaeny. Between them they would translate among English, Delaware and Shawnee to the Iroquoian tongue.

How does the fraught trade of alcohol factor into what happened next?

The English were trafficking rum. It sounds like an anachronistic word but it’s the right word. Native people in the region regarded it as trafficking. There was a treaty in 1721, the summer before this, in fact at John Cartlidge’s house, in which they asked the colonists to stop bringing rum into the back country. It was causing lots of social problems.

And part of what’s fascinating about the case is that the Pennsylvania colonists would insist that the fight between the Cartlidges and Sawantaeny broke out when he wanted more rum than they were willing to give him. But the Native informants said exactly the reverse, that the fight broke out when he refused to take rum in payment for all of the furs that he had offered. I find the Native version of this far more credible because the colonists had no incentive to admit that John was running rum. John had been brought before the courts for running liquor multiple times before this, so he personally was in legal jeopardy if he was running rum and other liquor. And the colonists themselves had signed a treaty promising to stop the trafficking liquor.

And the Native view of the case is actually the earliest dated record that we have [of the conflict]. After Sawantaeny was murdered, a group of envoys went from his home to officials in Maryland with word of this murder. And they said that he was killed when he refused liquor as payment for his furs.

This brings in another main character, Captain Civility.

Captain Civility was the lead spokesperson for the Native community at Conestoga. He was an accomplished linguist. He spoke multiple native languages from both the Algonquin language group and the Iroquoian language group. He did not speak any English, and that’s important to recognize. His role was weaving together Native people. And that, as much as anything else, also helps to really refocus the way that we imagine the Native world at this point, that their primary relationships were with one another, and they were dealing with this encroaching stress from outside from settler colonists.

Colonists would sometimes give mocking and ironic nicknames to people they wanted to subordinate. People who have heard of Captain Civility thought maybe this was some kind of colonial joke or pun. But Civility was a job title, not a personal name. It had been used by generations of Susquehannock Indians going back to Maryland in the 1660s. And it was the title that was given to someone who served as a go-between, who tried to bring disparate people together in community.

As a historian I find it helpful to look at the history of words and the history of language. And in the 17th century, civility really meant civil society in the sense of bringing people together. This job title was a 17th-century English effort at translating a Native concept of a job for someone who gathers people together in a community, in civil society.

He played a huge part in translating in all of these treaty encounters with the English colonists and trying to articulate Native perspectives in ways that they would be able to grasp. After the colonists have paid reparations and gone through ritual condolences, and after Edmund Cartlidge is reintegrated into the community, Captain Civility then says that they are happy that now the fur traders are civil. And I really like that all the while, the colonists thought they were evaluating his civility, but he was actually evaluating theirs.

Satcheechoe, who was a member of the Cayuga nation, is the one who actually went directly to meet with leaders in Iroquoia and get their perspective and then worked in tandem with Captain Civility. Civility meets with colonists both in tandem with Satcheechoe when he’s communicating the position of the Haudenosaunee, and he also appears in his own right on behalf of the peoples of Conestoga which are a more pluralistic community.

Your book is described as an “immersive” history—what does that mean?

I did want to recreate this world and people in three dimensions, not have cardboard characters. I really wanted to try to bring this world to life as best I could. At one point, my editor suggested I should streamline and just focus on the major characters. But all the people who might seem extraneous are all the subordinative people who never make it into history. And it’s really important to me to show them here.

For example, Alice Kirk is a property-owning woman who runs a tavern on the Brandywine River, and turns up to act as a translator at the first meeting between Satcheechoe and Captain Civility and the provincial council of Pennsylvania. That she had the linguistic ability to translate tells us so much about her tavern as a meeting place for Native people and colonists. It also tells us that Kirk was active in trading with Native people or she never would’ve achieved that linguistic competency. So we can see her as an economic actor and as a cultural go-between really in her own right.

So how successful were Captain Civility and Satcheechoe?

There is a really quite amazing scene when Civility and Satcheechoe take a string of wampum and wrap it around the Pennsylvania governor’s arm to symbolically pull him to Albany to meet with all the Native people who have become involved in this case. I actually think that they were symbolically taking the governor captive and saying, “We will bring you to Albany.”

The governor never admits that he has been basically forced to go to Albany. He always tries to make it sound as though he was just gracing them with his presence. But at the end of the day, he does realize that diplomatically, he cannot resolve this crisis if he does not pay them the honor of going to Albany. Because in Native protocol, the person who is offering amends needs to go and pay an honorary visit to the person deserving of that active reconciliation.

Native people believe that a crisis of murder makes a rupture in the community and that rupture needs to be repaired. They are not focused on vengeance; they are focused on repair, on rebuilding community. And that requires a variety of actions. They want emotional reconciliation. They want economic restitution.

And then they really want community restoration, to reestablish ties. The reconciliation piece means going through rituals of condolence. They wanted the attackers to apologize, to admit their fault. They wanted them to express sympathy for Native grief. They wanted the deceased man to be ritually covered, to be laid to rest in a respectful, ritualized way. And part of that respectful covering is the paying of reparations, actual payments that are made in compensation for the community’s loss. And then they want to then reestablish these community ties and connections. And that is exactly what happened.

The colonial Maryland records actually say, “The Native people want reparations.” The Pennsylvania colonists never really say explicitly, “We’re following Native protocols. We’re accepting the precepts of Native justice.” But they do it because in practical terms they didn’t have a choice if they wanted to resolve the situation.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.