SMITHSONIAN ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH CENTER

The Ugly Fish That Sings Its Own Song

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Toadfish1.jpg)

The sing-off begins when the sun goes down. Every night off the coast of Bocas del Toro, Panama, Bocon toadfish start calling from their burrows, trying to win over females by showing off their vocal talents and drowning out the competition.

If you’ve never heard of the singing toadfish, you’re not alone. They don’t have the charisma of dolphins or whales. They’re mud-colored reef dwellers, with bulging eyes, puffed-out cheeks and fleshy barbels dangling from their mouths. By most human standards, the toadfish isn’t exactly the prettiest fish in the sea.

“It’s kind of like a troll that lives under a bridge and sings,” said Erica Staaterman, a marine biologist who recorded individual toadfish songs in Panama for a new study published this month.

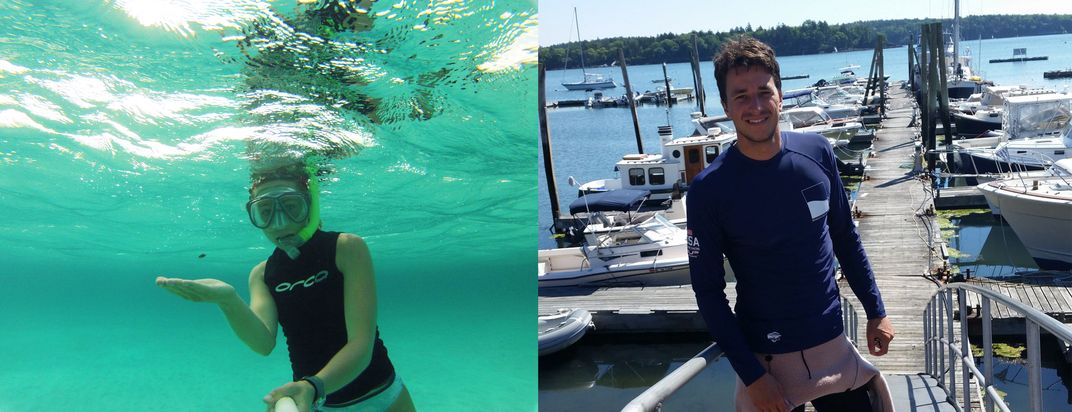

Staaterman journeyed to the Panamanian island of Bocas del Toro in 2016, during her work as a postdoc with MarineGEO at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. The island is home to a field station of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Staaterman and the biologists with her didn’t set out to record toadfish. They originally planned to map out the area’s overall “soundscape,” a collection of all the sounds of life on the reefs. (That study came out in 2017.)

“We were trying to record other stuff, but this species drowned out everything,” she said.

It didn’t take the team long to set up a new experiment to figure out what exactly the toadfish were jabbing about. Though toadfish are notoriously difficult to find, the biologists found over a dozen in burrows they had carved out under cinder blocks, which supported pipes for the research center’s aquarium facilities. (It’s not the first time fish have adopted manmade structures for their own purposes.) Male toadfish typically stay close to their burrows at night. If a male wants to get a mate, he will have to convince her to visit his pad. So for six nights, the biologists placed hydrophones near different burrows to record the toadfish’s nightly courtship songs.

The team recorded 14 different toadfish. However, they didn’t hear a harmonious chorus. Instead, the toadfish engaged in the underwater equivalent of a rap battle.

Toadfish sing in a predictable pattern of “grunts” followed by “boops.” The grunts, according to Staaterman, are merely the warmup. She likens grunting to a fish clearing its throat before it starts to show off its superior booping skills, the part of the song that’s supposed to attract females.

Each toadfish sang with its own distinct voice and style. They varied the number of grunts and boops, the duration of their calls, or the spacing between grunts and boops. But most toadfish weren’t content merely to sing their own songs. Often they would interrupt each other by just grunting when one of their neighbors started to sing. One night, Staaterman heard a trio of adjacent fish all trying to drown each other out. Two fish (“F” and “H”) had very similar calls and frequently interrupted each other. But “G,” situated between them, had a more distinctive call. Because he didn’t sing his own songs as often, and his song wasn’t as similar to theirs, the other two (F and H) spent less time interrupting him and more time interrupting each other.

And then there was the loner, “J.” J made his home under a lone cinderblock near the docks, nearly 70 feet away from the other 13 fish.

“He was just kind of hanging out somewhere away from the pack and doing his own little singing,” said Simon Brandl, another former Smithsonian postdoc who joined Staaterman in Panama. J did less interrupting than any other fish, and didn’t get interrupted much in turn. Brandl suspects this is because he was so far away—and he called so rarely—that the other fish didn’t regard him as a threat.

While the idea of fish having individual voices might seem surprising (Staaterman and Brandl’s study was the first to record them for this toadfish species), it may not be that rare. A handful of other toadfish species have also been recorded with distinct voices.

“It probably is a lot more common than we realize,” Brandl said. Midshipman fish can hum for over an hour. Croakers and grunts owe their names to the noises they make underwater. “Sound travels very well underwater, so it’s actually a really great medium to communicate.”

Perhaps the ugly, singing toadfish isn’t that special after all. We don’t know for certain yet—studying the voices of animals underwater is far more difficult than on land. As Staaterman points out, we’ve only recorded a tiny fraction of all possible fish noises. But that simply means there could still be an unmapped expanse of underwater music waiting to be discovered.