SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

A Catalan Choir Reinterprets Musician Raimon’s Anti-Fascist Lyrics

The Coral Càrmina of Catalonia answers the challenge to arrange a song from the Smithsonian Folkways catalog.

:focal(600x400:601x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/3e/a83eb317-dcaf-4423-a3b9-3c57fcff2bb0/coral-carmina-montserrat-1.jpg)

This story begins with a cancellation on March 10, 2020, at 9 p.m.

Following a stage rehearsal in the Gran Teatre del Liceu, the city of Barcelona’s opera hall, the cast and crew of the opera The Monster in the Maze canceled their upcoming performances. Three days later, the Spanish government declared a state of emergency involving a two-week mandatory lockdown that ultimately was extended to thirteen.

“The pandemic seriously impacted singers and choirs, especially Coral Càrmina,” Daniel Mestre, the choir’s director, recalled of those blurry days. “A couple days after the lockdown, the cases of COVID-19 started to mount among the singers: five, ten, seventeen, with seven admitted into the hospital, four of them in the intensive care unit. And we also lost a singer.”

In Catalonia, while few remember first-hand the Spanish flu of 1918, some people still living had tuberculosis in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Many more recall HIV and Ebola. In the Catalan imagination, however, such pandemic stories belonged to distant continents linked to low standards of hygiene, risky behaviors, or natural disasters. In other words, Catalans lacked a body of stories that would provide us with practical tips on how to survive a pandemic of this magnitude.

With almost no family and historical references to help us understand the risks we faced, we trusted that all would be well. Yet, the COVID-19 virus had found in the Liceu’s rehearsal room the ideal conditions for transmission: a large group of people expelling droplets containing the virus while singing in close proximity in a crowded indoor setting for a prolonged amount of time.

As soon as health officials confirmed the presence of the airborne virus in Catalonia, Lluís Gómez, vice president of the Catalan Federation of Choral Entities (FCEC) and an occupational physician, warned FCEC’s president, Montserrat Cadevall, of the dangers rehearsals posed for singers. As Lluís pointed out, everything was confusing: “At the time, there was a general disorientation about how to prevent the transmission of the virus, but it seemed obvious that it was transmitted via aerosols.” Although the International Festival and other performance and supporting events were already underway, the federation stopped all choral activity on March 10, 2020.

Despite the federation’s quick response, seventeen singers from the Coral Càrmina had already become infected.

“On March 11, I got a fever,” said Victòria Hernández, a soprano. “On March 21, I was admitted to Granollers Hospital. Two days later, I was in the ICU. Doctors had no personal protective equipment and used plastic bags to protect themselves. It looked like a war-zone hospital. The medical staff’s human touch despite the circumstances was outstanding.”

Chantal Pi, another soprano, said in an interview: “I was admitted on Saint Joseph’s Feast, March 19. When I was in the hospital, I felt it was important to tell my colleagues at the chorale I had just been admitted. Many responded by saying that they too had been diagnosed with COVID. It was then that I became aware that we had probably gotten infected during the opera rehearsals. Really, though, what matters is that back then, we were not aware of how one got infected.”

“March 22 is my birthday, and I had been admitted several days earlier,” said Delia Toma, a native of Romania who received many messages from friends in her home country who were unaware she was sick. “Everyone congratulated me, and I felt alone. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I was just suffering mainly because I have young children, and if my husband also got sick, social services would have had to take our kids into the system.”

The singers each found strategies to overcome not just the physical symptoms and their consequences, but also the multiple fears they inherited as first-wave patients. These individual stories, when passed down to children and grandchildren, will become the collective knowledge basis for the tools we will have to better handle future pandemic scenarios.

While all face-to-face choral activities ceased, a group like FCEC serves as a loom that knits the cloth of human connection through its singers’ voices. So, for Montserrat, it was essential that “the singers continued to be in contact and that those connections were not lost.”

The first thing the federation prioritized was explaining to its members how the virus was transmitted. The Conductors Forum, for example, which collaborates on research projects in the United States and Germany, shared its findings in its weekly newsletter with its 5,000 subscribers. In addition, a team of five doctors linked to the choral world—Lluís Gómez, Montserrat Bonet, Cori Casanovas, Pilar Verdaguer, and Lluc Bosque—wrote a prevention guide for choirs.

Secondly, the federation trained its conductors to use digital platforms so their singers could continue to meet and rehearse. As a result, they launched a series of lockdown concerts, the largest of which was the Saint George’s Day Concert, promoted by the Government of Catalonia’s Directorate General of Popular Culture and Cultural Associations. However, the most emotional performance was the December 29, 2020, broadcast on public television of El Pessebre, or “The Manger,” a nativity oratory composed by Pau Casals (1876–1973). Under the direction of Daniel Mestre, this was based on a text by Joan Alavedra (1896–1981) and recorded in different parts of Catalonia with the collaboration of many different choirs, soloists, and Mercè Sanchís on the organ of the Basilica of Montserrat.

The federation’s third action was to organize a cycle of conferences on composers and workshops for singers. The vocal technique workshop offered via Instagram had more than 2,000 viewers.

In short, although the harshness of the first wave kept the singers socially distanced, the federation did not allow the pandemic to prevent it from fulfilling its larger purpose: sponsoring performances, training artists, and supporting choral heritage.

A History of the Catalan Choir Movement

This drive is a constant in the tradition of choral singing in Catalonia, tracing back to Josep Anselm Clavé (1824–1874), politician and founder of the region’s choral movement.

Despite his numerous imprisonments, Clavé’s working-class choirs took root because they promoted both individual and community well-being through family concerts in gardens and parks. He also organized major festivals; in 1862, he was the first to introduce Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser in collaboration with the Liceu Women’s Choir in Catalonia. His choirs consisted of mostly migrant workers, and this was a place where they could learn about Catalan culture.

At first, the choral movement was fragmented by Clavé’s death, but it quickly rediscovered its purpose and redoubled its efforts. In 1871, Amadeu Vives and Lluís Millet founded the Orfeó Català, a choral group with the aspiration of producing an associated movement that responded to the ideals of the middle class instead. It thus expanded participation and the sphere of influence of Claverian choirs. In addition, Vives and Millet founded The Catalan Musical Journal, hosted several music competitions, and promoted the construction of the Catalan Music Palace, an architectural gem of Modernism recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and admired by more than 300,000 visitors every year.

During this period, more than 150 choral groups were born. Between the first and second waves of the 1918 pandemic, as people were eager to maintain and build connections, an umbrella association called the Brotherhood of Choirs—the predecessor of the Catalan Federation of Choral Entities—emerged to promote the artistic, social, and economic life of choirs.

The darkest period for the movement was the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, when many choirs disappeared. Clavé’s choirs continued to function because Franco’s dictatorial regime (1939–75) was interested in cultivating good relations with the working class. However, the regime did not tolerate the middle-class Orfeó Català.

The birth of the Capella Clàssica Polifònica (1940), conducted by Enric Ribó; the Orfeó Laudate (1942), under the direction of Àngel Colomer; and the Saint George Chorale (1947), conducted by Oriol Martorell, marked the second revitalization of Catalan choral singing. The festivities that surrounded the enthronement of the Virgin of Montserrat (1947) and other events that were allowed by the Franco regime allowed the choir movement to reconnect with its pre-war tradition without censorship. The activity of the Brotherhood of Choirs resumed under a new name: Secretariat of Choirs of Catalonia.

With the transition to democracy in 1975, choral activity slowly began to return to normal. In 1982, Oriol Martorell (1927–1996), a professor at the University of Barcelona—a socialist representative and a conductor—transformed the Secretariat of Choirs of Catalonia into the Catalan Federation of Choral Entities, which currently has 520 federated choral groups and about 30,000 members. It quickly joined the International Federation of Choral Music.

A Smithsonian Folkways Challenge Answered

Another place where choral singing is greatly loved is the United States, where before the pandemic there were 270,000 active choirs and more than 42.6 million singers. With that in mind, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage issued a challenge to choirs around the country and the world to mine the extensive Smithsonian Folkways Recordings catalog for material to rearrange, reinterpret, and recast the singers’ national histories. (Watch the first and second groups to accept the challenge.)

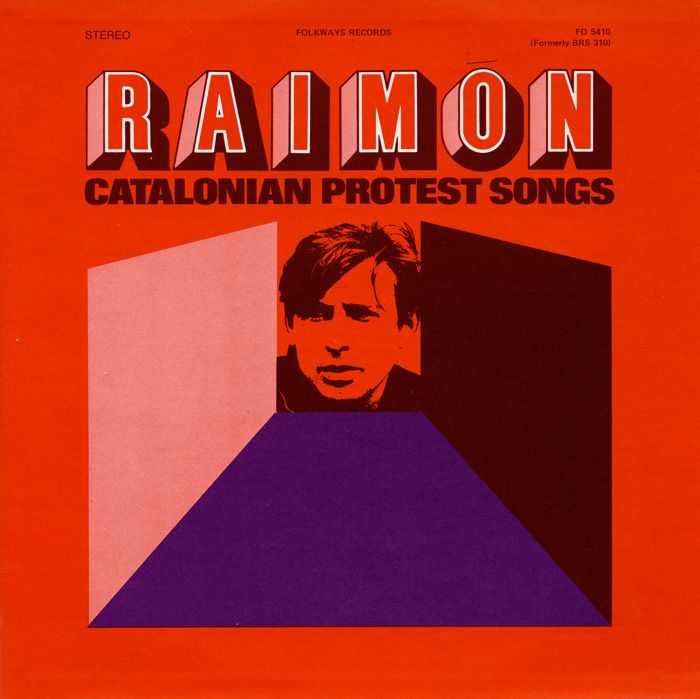

The Folkways collection is filled with the voices central to the twentieth-century musical lore of North America, with names such as Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Mary Lou Williams, as well as many others from around the world. But Daniel Mestre, always on the lookout to expand the Coral Càrmina’s repertoire, homed in on one of the label’s few Catalan artists: Raimon. His album Catalonian Protest Songs was released on Folkways in 1971, but Franco’s censorship had prevented it from being published in Catalonia.

Daniel asked the pianist, arranger, and composer Adrià Barbosa, who he had previously worked with on a concert in defense of migrants’ rights in 2017, to arrange a version of the album’s second track.

Daniel asked the pianist, arranger, and composer Adrià Barbosa, who he had previously worked with on a concert in defense of migrants’ rights in 2017, to arrange a version of the album’s second track.

“It couldn’t have been another song,” Daniel said in an interview. “It had to be ‘Against Fear’—because it is as current today as when Raimon composed it sixty years ago. Its message has that eternal power.”

Raimon, sitting a few feet away in the same interview, reacted with surprise. He observed that the song had always gone unnoticed, adding that he was delighted that it was finally getting some attention. “’About Peace,’ ‘About Fear,’ and ‘Against Fear’ are three songs I wrote on the theme of peace and fear,” he explained. “I wrote them in reaction to 25 Years of Peace.”

On April 1, 1964, the Franco regime celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the end of the Spanish Civil War with pomp and circumstance. It was a propaganda campaign to exalt the regime and legitimize it as the guarantor of peace. “That stayed with me here,” said Raimon, pointing to his heart. “Peace, fear—there is a trap. If there is fear, there is no peace.”

Raimon deftly pointed out the fascist fallacy: “You’ve waged a civil war, you’ve killed half of humanity, you’re still jailing men and women, and still killing them for twenty-five years since the war ended, and you call it 25 Years of Peace?!”

After a silence, Raimon laughed and added, “Maybe if the regime had not come up with that name, I would have never written these songs.”

Six decades after Raimon sang his experiences for Folkways, Daniel did his research and Adrià arranged “Against Fear.”

“I had never heard ‘Against Fear’ until I received the commission,” Adrià said. “When I listened to it for the first time, I thought, ‘The strength of this song is its lyrics, and the music is almost secondary. How will I arrange it for a choral group?’ After a few days of thinking long and hard, I had a breakthrough. I would take it into a harmonious and more poignant place with dissonances.”

“There were a number of dissonances with the guitar, but your arrangement has improved them musically,” Raimon commented. “All I can say is, do it again!”

Our laughter resonated in the ample, ventilated Balcony Room at Lluïsos de Gràcia, the association that generously allowed us to conduct the interview in person, socially distanced.

“That is why I thought of the solo,” said Adrià, picking up the thread of the conversation. “Besides, the song has a protest part and a hopeful part, and to emphasize that, the first part of the arrangement is full of dissonances, and the second has more counterpoint.”

Even though the historical context has changed, the song remains relevant. “Raimon wrote ‘Against Fear’ thinking of one enemy. His monster was the dictatorial regime,” Daniel observed. “Now we are overwhelmed by fear—actually, we are overwhelmed by lots of fears. We now have many monsters threatening us: the pandemics of COVID-19 and racism, the climate crisis, the rise of fascism.”

Storytellers such as Raimon, Adrià, Daniel, and Coral Càrmina strengthen us. The dissonances in the piece remind us how difficult and risky it is to break the silence. The counterpoint illustrates that the most efficient tool against fear is our love, our lives, and our stories. It is in the narrative process that we capture the cultural strategies that have helped us survive conflict in the past. It is in story that we find the cultural references that situate us, without having to feel like we are free-falling, blindly trusting all will be well. Let us not forget then, that to be resilient, we must tell our stories and call things by their names.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Annalisa and Raimon, Michael Atwood Mason, Halle Butvin, Sloane Keller, Charlie Weber, Montserrat Cadevall, Daniel Mestre and the Coral Càrmina, Emili Blasco, Pere Albiñana and the Sclat Team, Enric Giné and Tasso – Laboratoris de So, and Xavi G. Ubiergo and Andròmines de TV, all of whom made this article and the recording of “Against Fear” possible. I would also like to thank the cheerful collaboration of El Musical Conservatori Professional de Música – Escola de Músic de Bellaterra, Patronat de la Muntanya de Montserrat, Federació Catalan d’Entitats Corals, as well as Lluïsos de Gràcia for making it so easy. Jumping pandemic obstacles with you has been a privilege. You are sources of resilience!

Meritxell Martín i Pardo is the lead researcher of the SomVallBas project and research associate at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She has a degree in philosophy from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a doctorate in religious studies from the University of Virginia.

Reference

Aviñoa Pérez, Xosé. “El cant coral als segles XIX I XX.” Catalan Historical Review, 2(2009): 203-212. *0924 Cat Hist Rev 2 català.indd (iec.cat).