SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Chinese Poetry Left at Angel Island, the “Ellis Island of the West”

Angel Island Immigration Station was built in 1910 in the San Francisco Bay mainly to process immigrants from China, Japan, and other countries on the Pacific Rim. Its primary mission was to better enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and other anti-Asian laws enacted in subsequent years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/angel-island-poem.jpg)

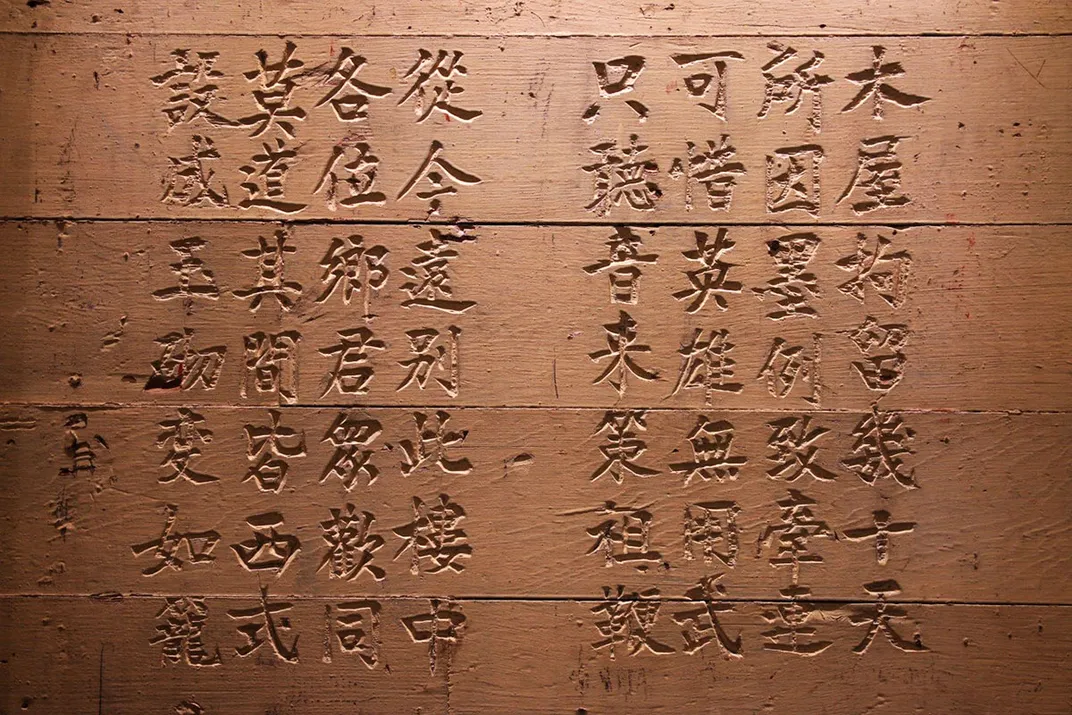

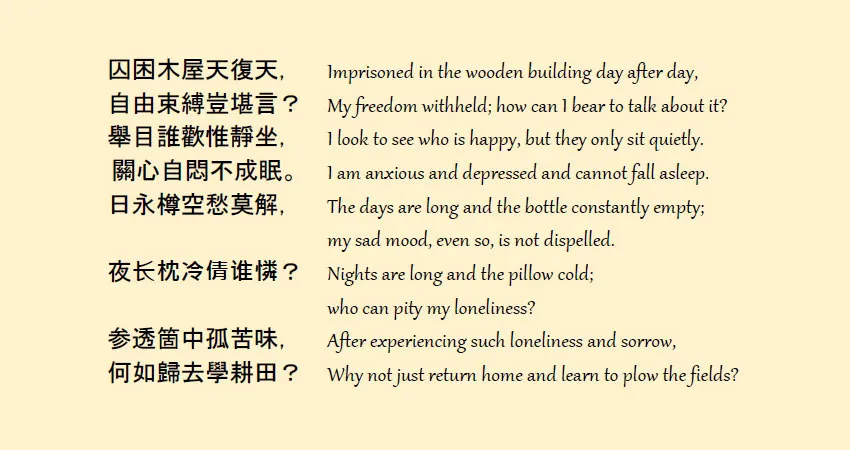

These lines are from just one of the hundreds of poems carved on the barrack walls of the Angel Island Immigration Station in the early twentieth century by Chinese detainees awaiting decisions on their entry status. As the first literary body of work by Chinese North Americans, this collection of poetry not only carries the secret memories of early Chinese immigrants but also vividly portrays a pivotal period in the nation’s immigration history, when various harsh discriminatory laws limited the entry of Chinese and other Asian immigrants.

I had read the poems and about their history, but it was not until I visited the site of the immigration station in 2016 and saw those carvings on the walls that I could deeply appreciate the detainees’ anger, frustration, and desperation. I can only imagine the hardships they endured on the isolated island upon arriving at this promising land of which they had long dreamed.

The Shadow of Exclusion

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act legally banned the free immigration of all Chinese laborers and prohibited the naturalization of Chinese immigrants already in the United States. It was the first national legislation against immigration based on race and national origin. For decades after, additional laws were passed that barred other Asian immigrants, such as Japanese, Koreans, and Indians, and to limit immigration from southern and eastern European countries.

Angel Island Immigration Station was built in 1910 in the San Francisco Bay mainly to process immigrants from China, Japan, and other countries on the Pacific Rim. Its primary mission was to better enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and other anti-Asian laws enacted in subsequent years. Newcomers to the island were subjected to severe interrogation, which often led to detentions—from a few weeks to months, and sometimes even years—while waiting for the decisions of their fates. The station remained in use until 1940, when a fire destroyed the administration building.

Besides a general physical examination applied for all immigrants regardless of age, gender, or race, Chinese detainees on Angel Island went through a special interrogation process. Immigration officials knew that a majority of Chinese immigrants claiming to be children of Chinese American citizens were just “paper sons” or “paper daughters” with false identities. In the interrogation, applicants were asked questions concerning their family history, home village life, and their relationship to the witnesses. Any discrepancies between their answers and those provided by the witnesses resulted in deportation.

Approximately one million immigrants were processed on Angel Island between 1910 and 1940. Of these, an estimated 100,000 Chinese people were detained.

Memories Carved on the Walls

One of the ways that Chinese detainees protested their discriminatory treatment on Angel Island was to write and carve poetry on their barrack walls. The poems were almost lost to history until a former California state park ranger, Alexander Weiss, discovered them in 1970 when the park service was planning to tear down the building and reconstruct the site. After the news of Weiss’s discovery spread through the local Asian American community, activists, descendants of Angel Island detainees, and volunteer professionals and students launched a campaign to preserve the detention barracks and the poems carved within it.

Since the 1970s, various efforts have been made to preserve the poems. Today, more than 200 have been discovered and documented. At the forefront of these efforts was the work of Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, who published translations of the poetry and excerpts from interviews with former detainees in the book Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940, first published in 1982 and republished in 2014.

The majority of poets were male villagers, often with little formal education, from China’s southern rural regions. Most of their poems follow the Chinese classic poetic forms with even numbers of lines; four, five, or seven characters per line; and every other two lines in rhyme.

The content ranges from experiences traveling to the United States and their time on the island, to their impressions of Westerners and determination for national self-improvement. Besides personal expression, some poems refer to historical stories or make literary allusions. Unlike the traditional way of signing the poems, few people put their names at the end of their work, most likely to avoid punishment from the authorities.

None of the collected poems were written by women. If women had written poetry, their works would have been destroyed in the women’s quarters, which were situated in the administration building and burned down in 1940.

Remembering the Sounds of the Past

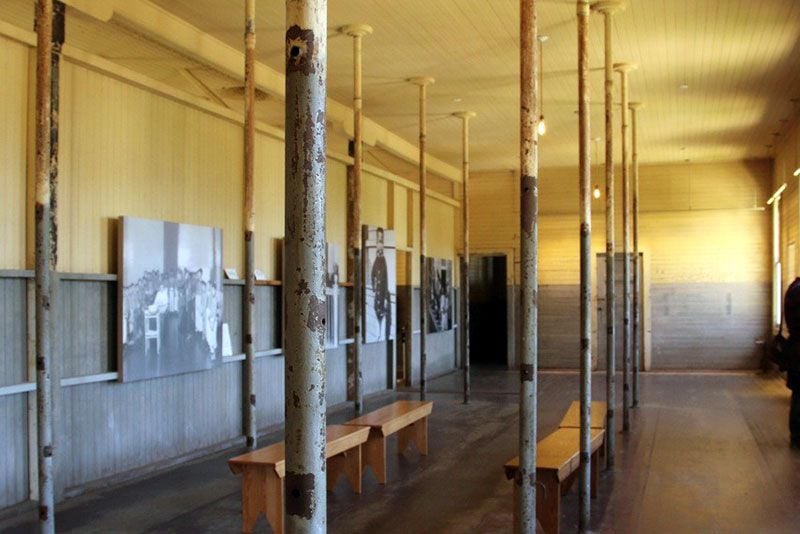

First opened to the public in 1983, the renovated detention barracks has been turned into a museum as part of Angel Island State Park. In 1997, the site was designated as a National Historical Landmark.

The historical discriminatory immigration laws seem to have become a thing of the past, but American inclusion and exclusion are still debated today—around such issues as, for example, childhood arrivals and executive orders proposing to ban refugees from certain countries. More than fifty years after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 removed the discriminatory national origins quotas, immigration policy and reform continue to be a source of great national concern. Millions of undocumented immigrants live in the shadows; thousands of immigrants are detained each year by the Department of Homeland Security. The surviving poems carved on the walls of the Angel Island barracks record the historical voices impacted by past policies of exclusion and have a certain resonance today.

Learn more about the Asian American experience through articles, videos, and lessons plans from the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

Ying Diao holds a PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Maryland, College Park. She was an intern with the 2016 Sounds of California Smithsonian Folklife Festival program. She is most grateful to Grant Din, Yui Poon Ng, Joanne Poon, and Judy Yung for their help in collecting data for this article.