SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

What They Carried When the Japanese American Incarceration Camps Closed

The closing of the World War II camps marks its seventy-sixth anniversary in 2021.

:focal(970x0:971x1)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Ishigo_sketch_sept_1945_Heart_Mtn_WY.jpg)

Dogs and cats abandoned, strawberries unharvested, a favorite chair left behind.

This could be a scene from the frantic days in 1942, when 110,000 Americans of Japanese descent and their immigrant parents were torn from their West Coast homes and forced by presidential order into U.S. concentration camps.

It was as if a major natural disaster, like a fire, flood, or hurricane, was hitting. Choices had to be made quickly. Exclusion notices had been posted on streets and telephone poles.

Within a week, or even days, homes and farms emptied as decisions were made about what to take. People could bring only what they could carry.

Nobuichi Kimura placed bound editions of Buddhist sutras, handed down through the family for generations, in a metal box and buried it outside the family’s home in Madera, California. He sold the house to neighbors at less than one-twentieth its value, privately hoping he would return someday for the scriptures.

An immigrant nurseryman in Berkeley secretly packed a box that his family learned about only after they arrived at the Tanforan racetrack, which had been converted into a detention camp. Had he packed a cache of special treats? They opened it up to find that he had filled it with eucalyptus leaves. He thought that he would never smell their fragrance again.

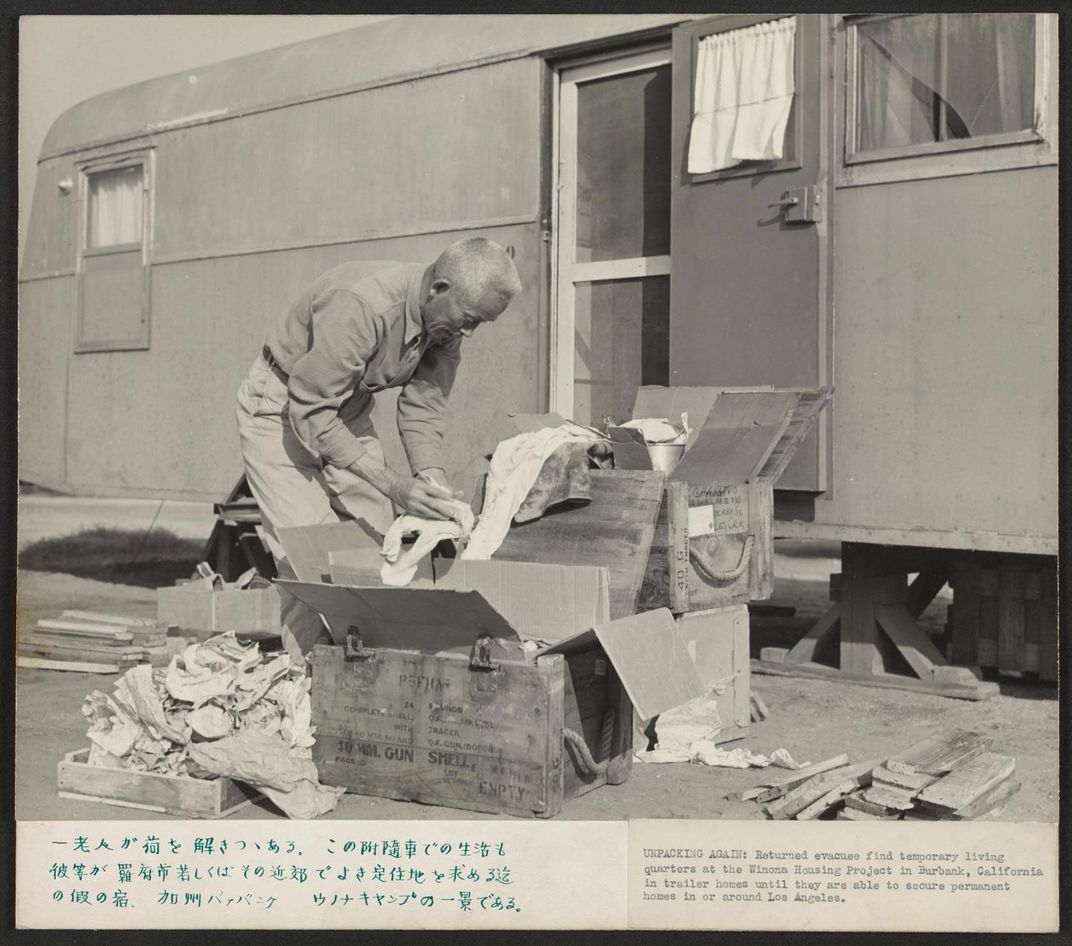

This landscape of loss and hurried departures occurred in 1942, but it also eerily describes the closing of those camps in 1945.

“When we were first ordered to leave Berkeley for camp, we had to get rid of most of our possessions, taking only what we could carry,” writes Fumi Hayashi, about heading for the Topaz camp in Utah. “Upon our release, we had little more than that.”

The closing of the World War II camps marks its seventy-sixth anniversary in 2021. It comes at a time when many Japanese Americans are linking their own family and community histories of incarceration with the Muslim ban, family separations, and the detention of immigrant children and asylum seekers today.

When protestors chant “close the camps,” they refer to the migrant detention camps and cages for children. In the summer of 2019, Japanese Americans of all ages joined Dreamers, Native Americans, Buddhists, Jews, and African American activists in Oklahoma to protest plans to confine 2,400 unaccompanied minors at the Fort Sill military base. After two demonstrations, it was announced that those plans had been put on hold.

Closing implies an ending. But the anniversary of the closing of the Japanese American camps is a reminder that the trauma did not end and neither did the historical pattern of scapegoating a vulnerable racial group.

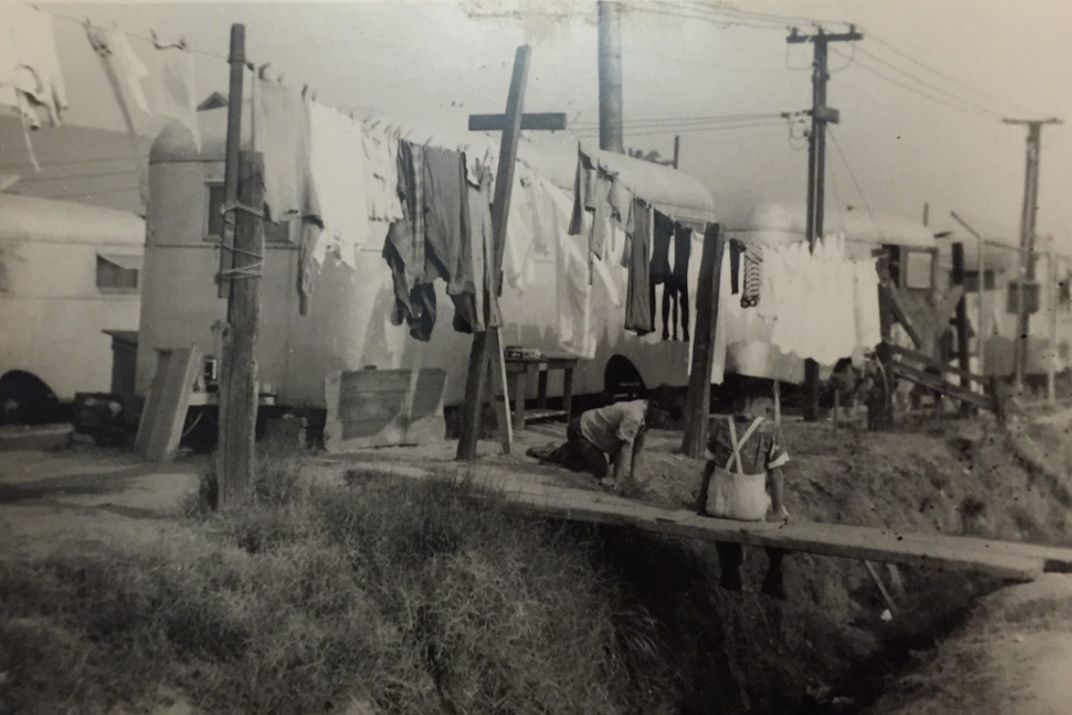

On December 17, 1944, one month after President Roosevelt won his fourth term, and with the Supreme Court about to rule the incarceration unconstitutional, Roosevelt signed an order to end the camps, nearly three years after his presidential order led to their creation. But the camps’ closing was prelude to a period of displacement, homelessness, and poverty for the many thousands of former detainees who had lost their livelihoods and had no place to go. Many ended up in government trailer camps where belongings sat outside.

The objects people managed to take were symbols of the deprivations of barrack life, resourcefulness, and relationships.

Kiku Funabiki, who was born in San Francisco, recalled one such object: a chair.

“With heavy hearts, we left the chair behind in the barren barrack room,” she wrote about a handsome seat that her brother, a trained engineer, had made using lumber pinched in a midnight run, dodging guards, at Heart Mountain, in Wyoming. It was a reminder of visitors who had sat in it. “We hoped some looter would take the loving chair.”

But Harumi Serata’s mother wanted no such reminders of life in Minidoka, Idaho.

“Mama said, ‘I don’t want to take anything we made in camp. Leave the table and chairs made with scrap lumber.’ She probably did not want to be reminded of our stay there, but against her wishes we did take the chest of drawers Papa had made along with one army blanket.”

In December 1944, when the exclusion orders banning Japanese Americans from the West Coast were lifted, some 80,000 people were still left beneath the guard towers.

A leave program had hastened the departures of 35,000 people. Those who could pass security clearance and show that they had a job offer or a college spot waiting for them—mostly the young—were released to areas outside the West Coast.

In the meantime, thousands of young Japanese Americans had been drafted or enlisted in the U.S. military to fight for the country that was imprisoning their families, while others, in protest, became draft resisters.

Those who stayed behind were disproportionately elderly immigrants. Not fluent in English, denied naturalization because of their race, and left without a livelihood, many didn’t want to leave. They feared outside hostility and vigilantism.

Administrators grew so concerned that the elderly would grow dependent on their secure albeit meager existence, that the situation was discussed internally. Continued confinement would lead to “a new set of reservations similar to Indian reservations,” officials worried, according to Personal Justice Denied, a government commission report.

Administrators worked to get everyone moved out by the end of 1945, by force if necessary. That year, the eight major camps, in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming were closed. Only the maximum-security Tule Lake Segregation Center, where thousands of resisters were confined in a prison of 18,000, stayed open until 1946. A tenth camp in Arkansas had closed in 1944.

One government propaganda photo showed an elderly immigrant shaking hands with the project director in a triumphal image of a successful closing.

There is no photo, however, of an Idaho administrator taking a relocation notice to a barrack. He was met at the door “by a Japanese gentleman who carried a long knife in his hand and informed the note-bearer that he was not interested in receiving the notice or making plans” to leave.

This description and others are recorded in the 1945 journal of Arthur Kleinkopf, an administrator at the Minidoka camp in southern Idaho, whose duties as education superintendent shifted, as the schools closed, to looking for property and people.

On October 9, an elderly man whose wife and daughter were already in Washington was found hiding under a barrack. The man’s packing was done for him, Kleinkopf wrote.

“He was then taken to the train at Shoshone, Idaho and placed in one of the coaches. When his escort left, he put the necessary money and papers in the old gentleman’s pocket. He removed these, threw them on the floor and exclaimed, ‘I no take it. I no wanna go. I jump out the window.’ The train pulled slowly out of the station with the old gentleman still aboard.”

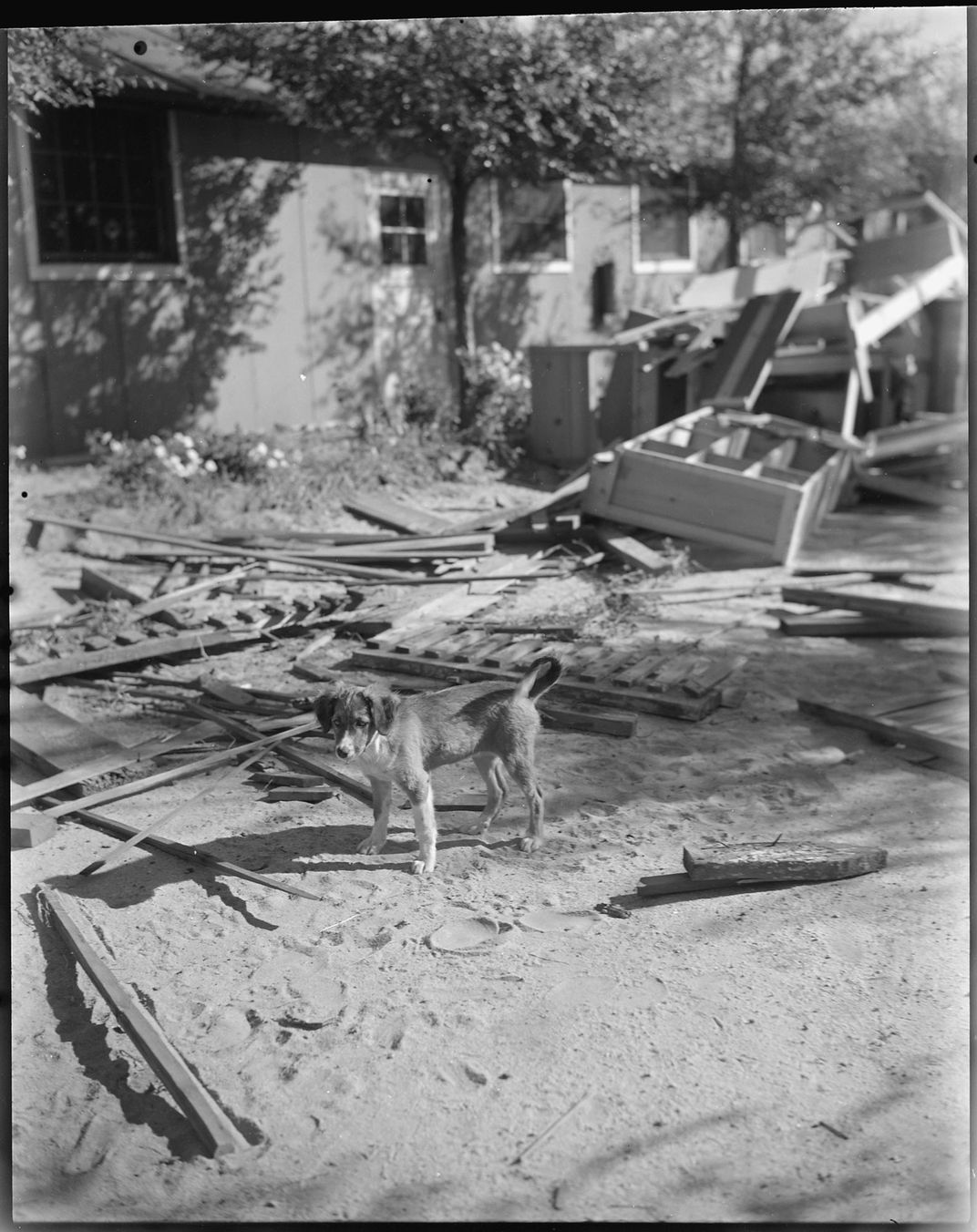

Two weeks later, after surveying a barrack, Kleinkopf wrote, “Everywhere there was evidence of hasty departure. Half-opened cans of food remained on one kitchen table. Boxes of matches were scattered about...As I went from barrack to barrack I was followed by an ever-increasing number of starving cats...A few people in referring to the search for remaining residents indiscreetly and discourteously referred to it as a ‘rabbit hunt.’” (October 23)

Half-starved dogs that had served as pets ran wild. “Attempts were made last night to kill some of the dogs which roam the project. The marksmen were not very good and some of the dogs were only wounded.” (November 19)

Beautiful plants still grew around the deserted barracks. Kleinkopf picked chrysanthemums and asters for the office and gathered strawberries for lunch, tiny echoes of the nurseries and fruit crops that three years ago had been abandoned on the West Coast. (October 1)

What eventually happened to the things that were carried out?

Family items saved by survivors all too often ended up in garages, attics, and the backs of closets. Too precious to discard, too painful to talk about, they languished in corners and in many cases were discarded by unknowing relatives after the owners died.

Much property got dispersed to local scavengers.

In Idaho, scrap lumber that was put on sale the day after Christmas at Minidoka drew a long line of trucks whose drivers also picked up dining tables and cupboards. “One man who paid $5 for his load refused an offer of $300 for it,” Kleinkopf wrote. (December 26)

Administrators helped themselves, too. After a final survey of the barracks on Oct. 23, Kleinkopf wrote that officials enjoyed a Dutch menu in the dining hall and chatted about their findings.

“Many of them had picked up curios of considerable value. Some had even removed pieces of furniture which had been left behind by the evacuees. There were canes, lamp stands, curios and novelties of all sorts and descriptions.”

Craft objects collected by scholar Allen H. Eaton in 1945 at five sites were nearly auctioned for private profit seventy years later, but instead they were rescued by an outcry from the Japanese American community. The collection was eventually acquired by the Japanese American National Museum.

The camp objects themselves are mute; it is for the generations that follow to preserve the things that were carried and the stories they hold. The repercussions of the WWII incarceration are still being felt and history is being repeated, says Paul Tomita, an eighty-year-old survivor of Minidoka. “Same thing, different era.” He and other Japanese Americans are taking action with the allies they didn’t have in WWII to defend people who are under attack now. The conditions which gave rise to their exile, and which gave birth to the things that they carried, must be resisted together.

Sources

American Sutra, by Duncan Ryūken Williams, 2019

Making Home from War, Ed. Brian Komei Dempster, 2011

Personal Justice Denied, Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1982

Relocation Center Diary, by Arthur Kleinkopf, 1945