How Black Women Have Changed the Face of Spaceflight

From Uhura to Katherine Johnson, learn about Black women’s impact on space travel in this excerpt from “Afrofuturism.”

:focal(1856x1856:1857x1857)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/e2/15e27292-e185-49f0-952e-8b3864184c07/nichelle_nichols_-_courtesy_of_nasa.jpeg)

On September 15, 2021, at age fifty-one, Sian Proctor became the first Black woman to pilot a spacecraft, taking the controls of a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft on its three-day orbital flight. She did so not as a NASA astronaut, but as a member of the four-person crew of the privately funded Inspiration4 mission. Flying in space was a lifelong dream for Proctor, but for much of her life, there were no astronaut role models who looked like her. Indeed, Proctor was already twenty-two years old when Mae Jemison became the first Black woman to fly in space in 1992.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/aa/0aaa4cd3-e429-49c9-863f-c01482a0e0e2/mae_jemison.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/f5/e9f5213b-e491-4a2e-86de-5e89f0e4ed42/uhura_costume.jpg)

During the early years of NASA’s human spaceflight program, equality was decidedly not on display. But recently recovered history has revealed that though women and minorities were not the public face of NASA, employees such as mathematician Katherine Johnson, a Black woman, were critical to the successes of the human spaceflight program, including the Apollo lunar landings. Johnson’s successes, and those of her colleagues, were told in the book (and successful movie of the same name) Hidden Figures. A groundbreaking NASA mathematician, Johnson spent her thirty-three-year career working at Langley Laboratory in Hampton. When the agency hired her as a “computer” in 1953, it had just opened some departments to Black women. Despite working in a segregated environment, Johnson rose through the ranks and performed calculations for some of NASA’s most significant space missions between 1953 and 1986. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 for her contributions to space travel.

NASA’s culture began to change, thanks in part to Black women working behind the scenes. In 1973, NASA fired and then was forced to rehire Ruth Bates Harris, the first Black woman to hold a senior position at the agency. NASA administrators labeled Harris a “disruptive force” after she authored an internal report decrying the “near total failure” of the agency’s equal opportunity programs. Despite being an early adopter of antidiscrimination policies, the agency’s staff was only 5.6 percent minority and 18 percent women (well below the government averages of 20 and 34 percent, respectively), and little diversity could be found in high civil service positions. As for the astronauts, the report pointed out, “During an entire generation—from 1958 until the end of this decade—NASA will not have had a woman or a minority astronaut in training.”

Firing Harris only brought NASA congressional hearings and bad press, and made the agency look out of touch with a changing nation. Congress ordered NASA to double its equalemployment budget and threatened to closely monitor its equal opportunity hiring and promotion programs. In 1974, Harriett Jenkins took over as NASA’s assistant administrator for equal opportunity programs.

Nichols’s portrayal of a future space explorer brought her into contact with real spaceflight, and she found that many NASA employees were dedicated fans of Star Trek. After hearing NASA scientists speak at Star Trek conventions and touring several NASA facilities as a VIP guest, the actor developed a passion for the agency. Her interest in space and her participation in NASA events earned her a seat on the board of the National Space Institute.

When NASA began recruiting astronauts for its new Space Shuttle program in 1977, the agency was dismayed to see that few women or minorities applied. Jenkins, still leading the equal employment opportunity efforts, and Administrator James Fletcher invited Nichols to meet with them to discuss their recruitment problems. Nichols explained that NASA had a long way to go to convince women and minorities that they were serious about diversifying the astronaut corps. But Nichols was impressed by Jenkins, the first Black administrator she had met, and was convinced the agency was sincere. Nichols proposed that NASA contract her company, Women in Motion, to help with a new publicity campaign aimed at women and people of color. NASA accepted.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/e2/15e27292-e185-49f0-952e-8b3864184c07/nichelle_nichols_-_courtesy_of_nasa.jpeg)

NASA gave Women in Motion six months to find “the astronauts of tomorrow.” Nichols threw herself into the task: in addition to a media blitz, she traveled the country, spoke at colleges and organizations in every major city, and delivered the message that is was time to change the face of spaceflight. Her work paid dividends. Harris's 1973 plea that the agency "must convince young minorities and women that is not NASA's intention to colonize the universe but that they too will have heroes and heroines in space," was answered in NASA's 1978 astronaut class. Notable astronauts added that year included the first woman to travel to space, Sally Ride; Guion "Guy" Bluford, Jr., the first Black American man to travel to space; and Frederick Gregory, NASA's first Black deputy administrator. Future astronauts Judith Resnik and Mae Jemison credited their careers to Nichols' campaign.

After the 1983 and 1992 flights of Bluford and Jemison, Black American boys and girls—and the country at-large—had new real-life space heroes and heroines. Since then, NASA astronauts Stephanie Wilson, Joan Higginbotham, and Jessica Watkins, along with Sian Proctor, have joined the ranks of spacefaring Black women—a remarkable, if still short list that offers hope for the future, yet also suggests the need for continued diligence. As Proctor’s example demonstrates, the rise of commercial spaceflight may create even more opportunities for astronauts of all backgrounds.

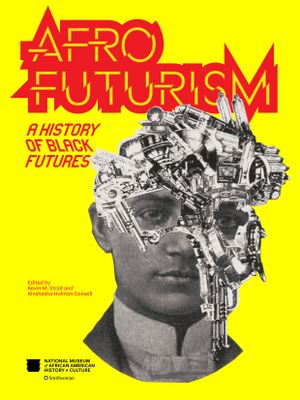

Afrofuturism is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

"Black Women Change the Face of Spaceflight" by Matthew Shindell excerpted from Afrofuturism © 2023 by Smithsonian Institution