Meet Four of the Weirdest Animals on the Planet

These strange beasts give mythical creatures a run for their money in this excerpt from “The Modern Bestiary: A Curated Collection of Wondrous Wildlife.”

:focal(801x603:802x604)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b2/45/b24599e3-317b-4c44-812a-edf2be341284/smithsonian_voices_header.jpg)

Welcome to The Modern Bestiary! Medieval bestiaries were books of beasts: collections of creatures containing natural history information (factual or otherwise), doused in didactic sauce with a strongly Christian flavor. Unlike its medieval counterparts, The Modern Bestiary is based on solid, peer-reviewed research. In addition, rather than using animals as a pretext for lessons on morality (I don’t think I am qualified to moralize), they are used here as a pretext to showcase biological concepts. The book features 100 real animals who are stranger than fiction, but below you'll find some of the strangest...

1. Zombie Worms

What happens when whales die? Their huge bodies fall to the ocean floor, reaching depths of several thousand meters. They arrive at the bottom relatively intact, since they sink quickly and there are no significant scavengers in the water column. Whale falls create unique, nutrient-rich ecosystems that may sustain creatures of the abyss for decades: in the cold depths, the lipid- and proteinrich whales are a rare treat. Their flesh is picked away by sharks, crabs, and hagfish (see page 108). Their skeletons are left behind, to be covered by beautiful, delicate, colorful flowers, resembling the fresh graves of beloved relatives. Except the flowers are not really flowers—they are worms. Zombie worms. And they are there to eat the bones.

Zombie worms, also known as bone-eating worms (a literal translation of their genus name, Osedax), are distant relatives of the more mundane earthworms. Small (just a few centimeters long), with pinkish-red “stems” and feather-duster-like “petals”—which are, in fact, respiratory palps used for breathing—they resemble plants more than animals. One species even gained the glamorous scientific name Osedax mucofloris, which translates as “bone-eating snot flower” worm. Like plants, these worms have roots, serving not just as an anchor but also as a way of obtaining food. This is a necessity, since, surprisingly for an animal that feeds on bones, zombie worms seem to have missed out on pretty crucial body parts: the mouth and gut. Instead, their soft root-like tissue secretes acid and enzymes to drill into the lipid-rich whale skeleton, and the dissolved nutrients are delivered to symbiotic bacteria living within the worms. These symbionts then metabolise the organic compounds, and feed the host. The acid borings are also used as shelter holes for the worms.

Bone-eating worms are pretty ubiquitous; they have been found at depths of between 30 and 3,000m, in the Atlantic and Pacific, from Sweden to California to the Antarctic. A single whale skeleton can house between half a million and a million adults. But here is the catch: those adults are all female. If you thought the worms’ feeding habits were weird, wait till you find out about their sex lives...

All Osedax are sexually dimorphic: the females look very different from the males. Inside their stem-like, gelatinous tubes, the zombie worm ladies harbor harems of a hundred or so microscopic males; the older and larger the female, the bigger her harem. Every male, or should we say man-child, is hardly more than a sperm-filled larva, reliant on a yolk droplet for energy (males don’t have the symbiotic bacteria to supply them with food). This polygamous relationship is a very strict-termed, no-nonsense barter: housing for sperm. The supremely fecund females produce a constant stream of larvae, and while most of the young won’t make it in the ocean depths, some lucky ones will find their way to another whale fall to settle down. It is likely that the sex of the larva is determined by environmental conditions—after spawning, those that land on dead whales become females, and those landing on the females, males. Females can colonize skeletons at densities of 3–20 individuals per centimeter, and once they settle, the late arrivals become males and live inside their girlfriends.

Unfortunately, commercial whaling reduces the number of sunken carcasses, and thus removes valuable sources of nutrients for animals such as the bone-eating worms, potentially leading to a lower species richness in the depths. Fewer whale carcasses means that larvae need to cover longer distances before finding a new dwelling—a task that isn’t easy anyway. And whatever their anatomical constraints might be, zombie worm females are certainly good at one thing: having sex on the graves of whales with a harem of underage males. For that unique skill, they deserve the chance to flourish.

2. Mudskippers

The quote “the word impossible is not in my dictionary” is attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte—although it also seems to be the motto of mudskippers, who are not deterred from climbing trees and scaling rocks by the mere fact that they are fish.

Mudskippers are a group of thirty-two mangrove-dwelling tropical species in the subfamily Oxudercinae, related to gobies. While some bear rather traditional scientific names—for instance, the giant mudskipper, Periophthalmodon schlosseri, celebrates the Dutch physician and naturalist Johann Albert Schlosser, and the pug-headed mudskipper, P. freycineti, the French explorer Louis de Freycinet— the New Guinea slender mudskipper, Zappa confluentus, honors the musician Frank Zappa “for his articulate and sagacious defense of the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

Frank Zappa stood up for freedom of expression, and mudskippers are equally tenacious; they won’t let anything hold them back. Of all amphibious fish, they are the most land-adapted, and may spend 90 percent of their time out of water. No lungs? No problem; they breathe either via water stored in their large gill chambers, or using cutaneous respiration—directly through the lining of their mouths and throats. Anything goes, provided they keep moist.

Suffering from dehydration? Mudskippers have a behavioral solution: they periodically roll in mud to keep their bodies lubricated; plus they are rarely further than a minute away from water. When not active, they take refuge in water-filled burrows, in which they also breed. Because the mud in which they build their lodgings is anoxic, and during high tide it is covered by water for a good few hours, mudskippers such as Scartelaos histophorus stock up on oxygen in advance. Their burrows are J-shaped, with an upturned portion not connected to the surface, which the fish use to create an air phase. They do so by inflating their mouth chambers with fresh air from the outside, then popping inside the house and releasing it there—up to fifteen times per minute—in preparation for the tide.

No feet to walk on land? Pah, these fish make do with fins. Their pectoral fins have a joint analogous to an elbow, used to propel the mudskipper forward in a motion resembling a person walking on crutches. While the pectoral fins do the lifting, the body is supported by a pair of pelvic fins, which are either fused, like a little suction cup, or unfused and gripping, allowing some mudskipper species to climb trees. These talented fish are also capable of hopping across water without getting their fins properly wet; they use their tails to bounce on the water’s surface before reaching a tree, rock or another bit of dry land on which they perch, in the most un-fish-like fashion.

When not channeling Napoleon or Zappa, mudskippers embrace their inner Donald Trump and build walls. Many species, like Boleophthalmus boddarti, are hugely territorial, and will demarcate their polygonal dominions with a 3–4cm-high partition. They construct it by carrying gobbets of mud in their mouths, and devote about 5 percent of their daily activities to building and repair work. Thus delineated, these territories are also foraging grounds for nutritious algae.

Other, carnivorous, mudskipper species face a different setback— the absence of a tongue. Fish are not huge in the tongue department anyway (see Tongue-eating louse, page 146, for replacement options), and generally just suck in the water that contains food. On land, however, a muscular tongue that pushes morsels to the back of the mouth for swallowing is a better option than suction. But what mudskippers lack on the anatomy front, they compensate for with innovation. They fill their mouths with water, move it forward to grab the food, and then suck it back to swallow—mirroring the action of tongued animals.Looking at various bits of mudskipper anatomy sheds light on vertebrate transition from water to land—and it seems a can-do attitude is just as important as the physical advantages land-based animals enjoy.

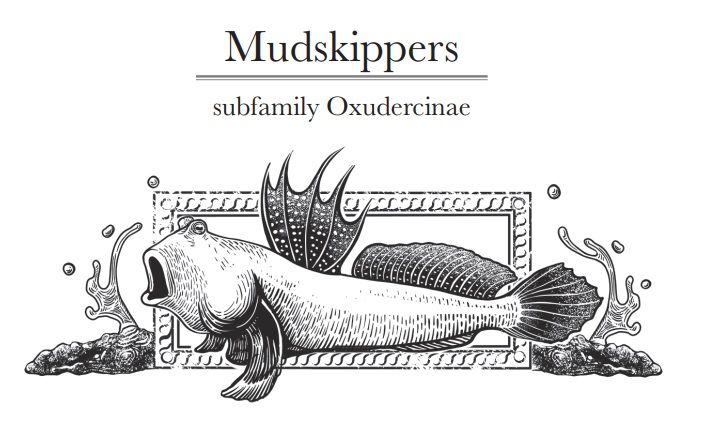

3. Common Potoo

“Branch out!” they say. Well, young potoos take this advice to heart—the species’ main goal in life is pretending to be a broken piece of tree.

Potoos—related to nightjars and Australian frogmouths—are a family of seven neotropical bird species, with the common potoo, Nyctibius griseus, being the most widespread. These birds inhabit areas from Mexico to Argentina—but unlike the tropical parrots or toucans, they are not brightly colored and flamboyant. The potoos’ plumage is incredibly drab, and for a good reason: it allows them to seamlessly blend in with the trees they pretend to be a part of.

In addition to the grayish-brown feathers, the pigeon-sized birds mainly consist of a mouth and unbelievably googly eyes, very much like something from The Muppet Show. The common potoo’s peepers are modeled after the Gruffalo: protruding, bright yellow, with black pupils. By contrast, the great potoo, Nyctibius grandis, has incredibly creepy jet-black eyes that seem to drill into the soul of whoever it is they are looking at. These species are nocturnal, and use their humongous headlights to spy insects (particularly beetles, moths and grasshoppers), which are swallowed whole by the ridiculously large potoo mouths. To hunt, the birds make quick dashes from their favorite branch and snatch prey mid-flight; they are not big on walking, and so do not try to pick insects from the ground.While their enormous eyes are very useful for their nocturnal hunting escapades, they are a dead giveaway to any predators during the day. However, the potoo’s defense mechanism is based around a brazen attitude and nerves of steel: it spends its entire days in broad daylight, motionless, disguised as a broken log. When danger approaches, the bird closes its eyes and mouth, and slowly stretches its head up, to make itself even more branch-like. The threat is constantly observed, either through a very slight squint, or, if the eyes are fully closed, through two small notches in the eyelids. The potoo keeps its eyes closed so as not to give away its position; it might shift ever so slightly to monitor what the threat is up to but there are no sudden movements, everything is nice and steady. While it might be playing a constant game of chicken and not moving until the last moment, if the predator ventures too close the potoo will either fly off, or abruptly open its freaky eyes and beak to scare away the opponent.

Life doesn’t change much for the potoos when it is time to start a family. They don’t bother with a nest—the female picks her favorite broken branch, stump, or fence post, ideally with a bit of a depression or knothole on top, and lays a single egg. At night, the monogamous birds take turns incubating the egg; during the day, it is mainly the male’s job. It does not seem like much of a sacrifice—after all, he is spending his days sitting still anyway; he might as well do it over an egg. By the time the youngster hatches, it is ready for the role it was born to play: that of a broken branch. The chick remains stationary, initially huddled in its parents’ feathers, and later, once it outgrows the cozy hideaway, next to Mom or Dad, or on its own. The youngster’s camouflage differs from that of the adults: the whitish, fluffy plumage resembles a fungus-infected tree. Still, it does the job. After fifty or so days of standing motionless with its parents, the young potoo is ready to start standing motionlessly solo. From a low-maintenance childhood, to a smooth period of adolescence, to a chilled-out adulthood—these birds may not have accumulated a store of exciting anecdotes in their lives, but they know how to elevate monotony to an art form.

4. Vampire Finch

If you find yourself marooned on an inhospitable island, follow the example of Robinson Crusoe: make the most of what is around you and be adaptable. The forebears (forebirds?) of Darwin’s finches have done just that.

Some 1.5 million years ago, ancestral finches from South America found their way to the Galápagos Islands, almost 1,000km west of continental Ecuador. The castaways gave rise to eighteen species of Darwin’s finch (technically not true finches, but tanagers classified in the subfamily Geospizinae), which currently inhabit the archipelago. Present-day Darwin’s finches are all small and drab in color, but show an astounding diversity of beak sizes and shapes. These beaks, ranging from the huge, broad, and blunt bill of the large ground finch to the petite, narrow bill of the warbler finch, are adapted for distinct diets. While broad-billed birds thrive on islands with nuts, finches with longer and more slender bills take advantage of sites with cactuses, and those with the smallest beaks specialise on insects. Each type of finch forages for a slightly different kind of food—biologists would say that each species occupies a different ecological niche—and consequently avoids getting in the way of the others, so much so that over time the populations with distinct beaks became separate species. Darwin’s finches are therefore a model example of adaptive radiation, a phenomenon where species diverge from a common ancestor as they adapt to different ecological opportunities—and a diagram of the birds and their varied beaks is a staple fixture in evolution textbooks.

But while ground finches feed on seeds, and tree finches on insects, one type of finch, inhabiting the two most remote islands, Wolf and Darwin, takes a more gruesome path. Originally thought to be a subspecies of the insectivorous sharp-beaked ground finch, this bird has recently been elevated to its own species: the vampire finch (Geospiza septentrionalis). During the wet season, when food is abundant, vampire finches will happily forage on insects, seeds or nectar. However, in the dry season, the lack of food and drinking water drives the birds to switch to more grisly sustenance: blood. This iron-rich snack forms such a significant part of their diet that vampire finches acquired a specialized gut flora, containing bacteria usually found in the intestines of carnivorous birds and reptiles.

For its sanguineous meal, the audacious little bird targets larger species, particularly red-footed and Nazca boobies (see page 162). The dainty vampires perch on the boobies’ rumps and draw blood by pecking with scalpel-like beaks at the base of the wing feathers. The flowing blood attracts more finches, and a queue forms around the victim—everyone wants a sip. Adult boobies are not pleased about it, but seem to mind the vampire finches less than the flies their wounds attract. Young, fluff-covered boobies have a much rougher time. The finches peck relentlessly at the softest body part, the cloaca, sometimes causing the baby boobies to flee their nests— with fatal consequences.

To make matters worse, vampire finches also feed on booby eggs— a remarkable undertaking when one realizes that the egg weighs more than twice as much as the 20g diner. The little bird uses its extra-sharp beak to pierce the shell, or it can kick the well-packaged lunch into a rock or over a cliff to open it. The initial effort pays off, since the egg provides excellent sustenance.

Thankfully, Robinson Crusoe did not have to resort to becoming a vampire—but perhaps, given a few hundred thousand years, his descendants would have?

The Modern Bestiary is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from The Modern Bestiary © 2022 Joanna Bagniewska

Illustrations © 2022 Jennifer N. R. Smith