Building a Great Society on Sesame Street

Take a walk down Sesame Street and learn how the show pushed boundaries for social change in this excerpt from “Entertainment Nation.”

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b4/19/b419e803-387c-4294-91fb-d3a9e0e9ccce/sesame_street.jpg)

On November 10, 1969, a new kind of children’s television program premiered on public television stations across the United States. In the opening scene, an African American man named Gordon walked down an urban street with a multiracial girl named Sally, welcoming her to the neighborhood. “Sally, you’ve never seen a street like Sesame Street. Everything happens here. You’re gonna love it,” Gordon said as they passed by time-worn brownstones, fire hydrants, and trash cans. Before long, Sally met an eight-foot-tall yellow bird, a mischievous orange puppet who loved to sing to his rubber ducky in the bath, and a grouchy orange (later green) monster who lived in one of those trash cans on the street. In between the segments of humans and puppets interacting on the street, colorful animation, catchy music, and a guest appearance by Carol Burnett, the show taught numbers, letters, and life skills. Rather than being sponsored by companies marketing sugary cereal or action toys to children, this program was brought to viewers by the letters W, S, and E, and the numbers 2 and 3.

The most remarkable thing about Sesame Street wasn’t its music or cast of monsters: it was the mission. For the first time, educators and child development experts worked together with creative talent to produce a national television series with a curriculum, a research team, and above all, the goal of functioning as an educational resource for minority and lower-income children. Amid the Civil Rights Movement and the tide of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society social welfare legislation, the Children’s Television Workshop set out to prove that television could be a powerful force for social change.

A young television producer named Joan Ganz Cooney believed there was. Cooney established the Children’s Television Workshop, with funding from the Carnegie Corporation, the Ford Foundation, and the US Department of Education, to develop a model educational children’s television program. Her research showed that despite the advances made by federal programs like Head Start, only half the nation’s school districts offered kindergarten classes. The lack of preschool in disadvantaged communities, Cooney wrote, resulted in an academic achievement gap that had lasting socioeconomic effects. Meanwhile, by 1960, 87 percent of American households owned a television, and children were watching an average of twenty hours of television every week. Cooney saw an opportunity to use that television time to educational ends.

In the summer of 1968, Cooney organized a series of seminars with experts in child development and education, animators, advertisers, children’s book authors, and the puppeteer Jim Henson to draft a curriculum and shape the concept for what was then blandly titled Early Childhood Television Program. At this point, Henson and his Muppets were best known for their work in television advertising, which was fitting given Cooney’s emerging concept for the show. Advertisers knew the medium better than anyone else. If the workshop team could harness the production values and addictive qualities of television commercials to promote reading comprehension instead of toys and cereal, this new show could help a generation of youngsters, especially in disadvantaged communities.

Some of the creative talent Cooney hired was inspired to join the team after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. For them, this seemed like a critical moment to harness the power of television to serve African American communities. The show would be set in an inner- city neighborhood, with authentic trash cans, stained sidewalks, and brownstone stoops that would feel familiar to its target audience. In an attempt to counter harmful stereotypes, the show’s human cast would feature a stable middleclass Black family, Gordon and Susan, living harmoniously with their white neighbors and diverse Muppet residents. Early guest stars included James Earl Jones, Mahalia Jackson, and Nina Simone singing “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.” A Department of Utilization at CTW was dedicated to community outreach, setting up “Sesame Street centers” at churches, libraries, and community centers where those without televisions could watch the show, and to distribute related educational materials for use in schools and at home.

Besides teaching literacy and numeracy, the show also taught life and social skills: how to deal with feelings, big changes, people different from you, and conflict. In this regard, the Muppets were the show’s secret weapon. Big Bird was a naive and sometimes clumsy six- year- old, Bert and Ernie were mismatched roommates who learned to navigate their differences, and Oscar the Grouch was a grumpy, trashcan- dwelling monster who was nevertheless a valued member of the neighborhood.

Sesame Street was an immediate success, lauded for its combination of education and entertainment. Research commissioned by CTW showed that regular viewers scored higher on standardized tests of reading, writing, and comprehension than nonviewers, with gains particularly noticeable among children from disadvantaged communities. Ten years after its debut, the show was drawing an audience of nine million children for every broadcast, and one study found that 90 percent of all children in low- income households were regular viewers.

Like many other Great Society projects of the 1960s, however, Sesame Street has weathered criticism from across the ideological spectrum—criticism that has kept its funding and survival tenuous despite its huge following. As early as the Nixon administration, with its federal support in peril from conservative opposition to public television, CTW turned to generating revenue from books, toys, and its chart- topping soundtrack records. Some critics then accused Sesame Street of becoming just another children’s television cash cow. More recently, although its controversial move from the PBS network to HBO has benefited the show financially, some have decried the change as a betrayal of the series’ original mission. (New episodes premiere on HBO, but public television airs reruns.)

Sesame Street has also struggled over the years to fully achieve its mission to represent a diverse and multicultural nation. Debate raged behind the scenes and among critics when the Muppet character Roosevelt Franklin, a speaker of African American Vernacular English, was added to the show in 1971. Performer Matt Robinson championed the character, who was popular among viewers, as an intelligent, hip, and unmistakably Black member of the Muppet cast, but some reviewers and researchers feared that Franklin’s dialect and mannerisms reinforced stereotypes and taught bad habits. When Latina/o activists demanded greater representation, three characters were added for the 1971 season: Rafael, Maria, and Luis. In 1991, the bilingual Muppet Rosita joined the cast. Julia, a Muppet with autism spectrum disorder, is a more recent addition. As the other characters learn about her condition, they also learn that she’s just as valued a friend as any other; they may just have to play with her a little differently.

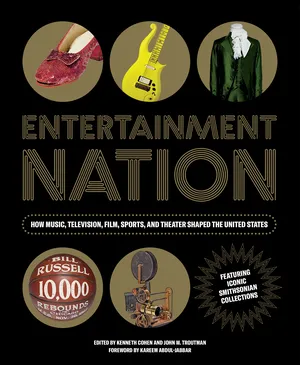

Entertainment Nation is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States © 2022 by Smithsonian Institution