Meet Monsters Under the Sea

Learn about large extinct “fish lizards” known as ichthyosaurs with this excerpt from “Ancient Sea Reptiles.”

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/f1/1ff1b733-e5f5-4482-9a89-6cb3913d05a2/smithsonian_voices_cover_-_ancient_sea_reptiles.jpg)

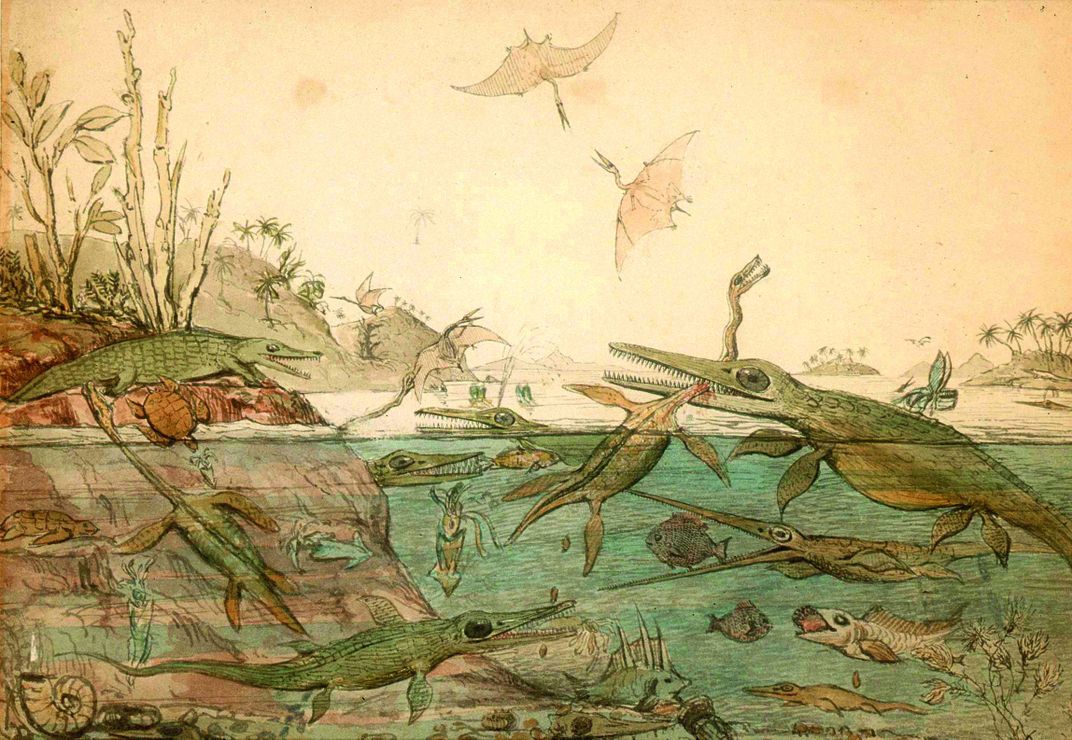

The ichthyosaurs, sometimes called ‘fish lizards’, are among the most recognizable of the Mesozoic marine reptiles. Articulated skeletons show that most were streamlined and shark-shaped, and usually between 2 and 6 m (6½ and 19¾ ft) in length. A few giants reached 20 m (65½ ft) and more. Typical features include long, slender jaws, conical teeth, enormous eyes, two pairs of fin-like limbs, a dorsal fin and a crescentshaped tail fin. This description applies to the members of Parvipelvia, the group that originated at the end of the Triassic and persisted until the middle of the Cretaceous.

Several non-parvipelvian lineages evolved during the Triassic. These were not as anatomically homogenous as parvipelvians and evolved in several different directions. Some had blunt-tipped or rounded teeth, while others were large, even enormous, predators. All, however, were built for life in water and were devoid of features that might allow movement on land.

The absence of fossils that look like proto-ichthyosaurs – that fill the gap between these aquatic species and their terrestrial ancestors – has left experts in the dark on ichthyosaur origins, and on what the earliest stages of their evolution were like. Recent discoveries have changed that. Several proto-ichthyosaurs are now known, including the hupehsuchians and nasorostrans of the Early Triassic. All are from China, suggesting that ichthyosaurs originated in the Eastern Tethys Ocean. In addition, new specimens of Triassic ichthyosaurs such as Utatsusaurus from Japan have shown that ichthyosaurs almost certainly descended from ancestors with a typical diapsid skull architecture.

The fact that ichthyosaurs of several groups are known from the oldest part of the Early Triassic shows that their evolution was well underway by this time, just five million years after the extinction event that ended the Permian, 252 million years ago. They evolved extremely quickly, reaching giant size in that relatively short time.

Certain Triassic ichthyosaurs are especially odd and cannot be placed within the major groups. In some cases, their ichthyosaurian status has even been doubted. Among these are the omphalosaurs of Early and Middle Triassic central Europe, Spitsbergen and the USA. A pavement of buttonlike teeth is present across their upper and lower jaws and one species had a spatulate lower jaw.

Numerous trends are seen in ichthyosaur evolutionary history. The most obvious involves the transition from anguilliform swimming (using undulations of the body and tail) to carangiform (tail undulations only) and ultimately thunniform (the fastest, using just the tail fin). Ichthyosaurs retained both limb pairs throughout their evolution, even though the hindlimbs of parvipelvians were much reduced. Other trends include a reduction of the skull behind the eyes and a change to the scapula from a fan-shaped plate to a slender blade with a broad base.

Until recently, it was generally thought that ichthyosaurs had their heyday in the Triassic and Early Jurassic and persisted at low diversity from the Middle Jurassic until their extinction in the middle Cretaceous. A huge number of studies and discoveries have overturned this view. They show that parvipelvians thrived at diversity in the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, the group finally waning around 100 million years ago at the end of the Early Cretaceous. Virtually all of these late-surviving forms belong to the same group, Ophthalmosauridae, so it is still true that this final flowering of the group did not fill as many roles in ecosystems as did the ichthyosaurs of the Triassic. The final, middle Cretaceous extinction of the group was related to an overturn that happened in marine ecosystems at this time.

For all our knowledge of ichthyosaur diversity, we have yet to discover any species that inhabited estuaries or freshwater. It might be that ichthyosaurs never invaded these environments, perhaps because other reptile groups prevented this, or because there was never any evolutionary pressure for them to do so. It might be, however, that estuarine or freshwater ichthyosaurs did exist but haven’t yet been properly recognized. Hints that they did exist come from rare, fragmentary platypterygiines from the Lower Cretaceous freshwater sediments of southern England, specifically the Purbeck Limestone in Dorset and the Wealden in West Sussex.

Platypterygiines include the last of the ichthyosaurs. Fossils show that as many as seven platypterygiines were in existence around 114 million years ago, but that they declined late in the Cenomanian age around 94 million years ago and failed to survive beyond it.

Ancient Sea Reptiles is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Ancient Sea Reptiles © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London, 2022