Remembering a Mississippi Blues Icon

In this excerpt from a long-lost manuscript, follow the author as he meets with many people who knew the musician Robert Johnson personally

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4c/7a/4c7a8bdc-3fb0-44b1-972d-b3beea07ec8d/macks_1968_research_map_for_smithsonian_voices.jpg)

My long search was now at an end. It had come suddenly, almost unexpectedly. After all the fumbling and the dead ends, I had found people who had known Robert Johnson. They knew him by another name, but they knew him as a neighbor and friend, had watched him grow up and drift away. They shared not isolated recollections, but a whole interlocking pile of them. There was much more than I could thoroughly digest amid my questioning, listening, making notes, ironing out inconsistencies in dates and chronology, and straining to understand those nuances that shade and color a man’s nature but which are hard for all of us to articulate.

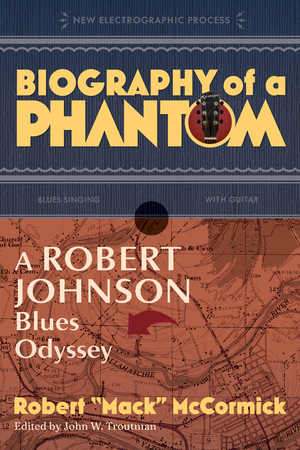

Whatever “midnight streets” Johnson had traveled, the dusty road that runs due west from Robinsonville straight to the levee was the one where he was a familiar face, a man known easily, if not deeply, with the familiarity of long association. Ironically, my painstakingly marked-up map had not helped me in the ways expected. The marks I’d made around Robinsonville and its outskirts were several in number, but they were part of a chain, largely tracing back to one source. By comparison with other towns I’d pinpointed, Robinsonville had only seldom been mentioned by independent sources, whereas places such as Helena, Arkansas, were mentioned and seconded by as many as ten different people I’d interviewed separately.

Robert Johnson himself hadn’t helped any. He left no songs mentioning Tunica County, Commerce, or Hazlehurst. He had nothing to say about his home or the two major roads—Highway 51 and Highway 61—that everyone else was making songs about. He had been born and lived just off of Highway 51, and his later home was within a short walk of Highway 61, yet he mentioned neither. Johnson didn’t sing about his homes, but rather about the places he passed through and knew as a brief visitor. He overthrows the notion that a blues singer can be traced by going to the places he sings about. That often works, but not always.

My map had helped primarily by illuminating the area where my search had to concentrate: the Delta just below but near Memphis. It had simply underscored what everyone had known and presumed, dramatizing the pattern so that it eventually forced me back to the Delta often enough to hit paydirt. There were fairly clear indications that Robinsonville was the right area, but even there Johnson’s home base remained elusive until I went two miles in the right direction.

The next day my visit came to an appropriate finish. Everyone in the Leatherman neighborhood who had known Robert Johnson had wanted to know whether they could hear his recordings again. They had asked this repeatedly, and in return I suggested that perhaps everyone could gather at one place. They passed the idea around, and Cleveland and Lula Smith offered the use of their house and invited the rest of the community to attend. They decided to make it around dusk.

It wasn’t as old and gray a gathering as I had been expecting. My months of searching had lent a feeling of antiquity to the whole process of scrounging for information about someone who had been dead for years. Part of it had to do with the rush of changes that had taken place in the Delta; Robert Johnson had lived during an era that seemed far in the past. Yet if he had been alive, he would have been a mere fifty-eight years old at the time. So the people who had known him were now in their fifties and sixties.

"He was always like that. He was dying faster’n he was living.”

Cleveland Smith stood in the middle of his living room, a heavyset man with one arm set akimbo on his hip, listening for the tread of steps on his porch. When they came, he’d wait until the screen door was pulled open and the visitor hollered; then he’d shout the person inside, beckoning, talking, and pointing out chairs all at once. It was a country way of entering a house and being welcomed. If you didn’t holler out when you approached a Robinsonville house, or you did something suspicious like knock on the door, a dog would bark or even be prone to attack.

Phax “Butch” Long was the oldest of the group that gathered. His wife, Sally, was the only one who seemed apprehensive, as if she wasn’t certain she wanted to hear the voice of a dead man she’d known so long ago. When she arrived she explained to Lula Smith, “I had to come. See, I nursed Robert when he was young, so I had to come.”

Alex Clark came with several others, arriving in stained clothes because they had come directly from work. He seemed particularly keyed up, proud of his association with Johnson. There were others who had known him, some who had known his family, and a few who came just to join in on the occasion, all active working people, looking forward to more years of life.

The room was filled with a jovial, eager feeling and a sense of expectancy. These people had known Robert Johnson—or Robert Spencer, as they spoke of him—as only a boy and young man. He was part of their collective youth. They’d watched each other grow older, but his memory and music reminded them of their youth, of their dances and frolics and their early social life in the countryside.

There was a flurry of talk among the first arrivals about the records they’d once owned. Many of them had bought Johnson’s records as they had appeared in the 1930s, but over the years the discs had been broken or lost, left behind in flooded or burned-out homes. None of them had heard his voice in nearly thirty years. They found it hard, even impossible, to imagine that the old recordings were once again on sale in ordinary record stores. They watched patiently as I set up a portable phonograph, then passed around the microgroove LP album that Columbia had issued in 1961. The jacket cover was a dusky red color, with a painting of a Black guitar player hunched over a guitar. It’s a high-angle view, looking down on the figure, his face hidden from view. He is wearing a shirt with vertical stripes.

One of the people took the album and rubbed his hand over the surface of it, as if to see whether the picture would come off. He shook his head and said, “I never saw him wear any such shirt as that.”

Someone else disagreed. “I saw it. He had a shirt like that. Maybe not exactly like it, but close.”

The shirt, of course, like the other elements in the cover, had been the product of artist Burt Goldblatt’s imagination. The feeling of it was right. It was strong and evocative, but it hadn’t been meant literally. The guitar was a bright orange, and Johnson’s skin was a glossy pure black.

“He wasn’t near that dark,” one of the women said. She took the album and read it out loud, putting to rest a little of the worry that the whole enterprise was a hoax. “It sure says his name: ‘Robert Johnson.’” She read on: “King of the Delta Blues Singers.”

“Well, that’s right enough.”

“He surely was that.”

“That’s true. That’s true.”

Several others got up to inspect the album. They asked how much it cost and were staggered when they were told it was $4.98. Someone I hadn’t seen before spoke up: “You selling these?” There was a little hostility in the way he said it. I told him no, and someone else answered, “I wish he was. I’d like to buy one.” The man retorted, “That’s too much money for one record.”

A younger man came to the rescue, explaining that it was a different kind of record than the ones they were thinking of: “There ain’t just two songs on this.” He stopped to count a minute, flipping the jacket over, and then announced that there were sixteen songs in the album. “This is a whole different thing.”

This young man was wearing an Air Force uniform, and someone told me he’d been stationed in Germany for several years and was visiting home before going to another foreign post. “He speaks a couple of the languages from over there,” I was told. “Reads them, too.”

I slipped outside for a minute, and by the time I’d returned they’d done some arithmetic, figuring that the new album had the same number of songs as eight of the old 78 rpm records, which had cost thirty-five cents each. It worked out to a total of $2.80 as the original price for the same amount of music.

“Twice as much. That ain’t bad.”

“Most things have gone up more than that. Way lots more.”

“You right there,” a woman laughed. “I wish I could shop at the store and not pay but twice as much as I paid back then.”

They watched, still skeptical, as I slipped out the record and set it on the turntable. When the music started, breaths were sucked in and held for the eight seconds of sharp, biting introductory guitar playing. An astonishing degree of recall can be triggered by familiar things brought back like this. At the first phrase, Johnson’s clenched voice singing “I went to the crossroad,” half the people in the room responded. Two of them said the next word, “fell,” aloud, not after the singer but with him. They finished the line with him, “fell down on my knees,” and just that quickly the intervening years fell away. One man phrased the words right with the voice. Others drowned out both him and the recording, exclaiming at one another. The group erupted with comments.

Someone said that he’d owned a copy of that very record and tried to remember what had been on the other side. Another man named it—“Ramblin’on My Mind”—before the first man could think of it. One of the women noticed that the singer referred to himself as “Bob” in the song. “I always knew him as Robert,” she said.

Others agreed that Robert was how they’d known him, but one of them said, “I think they called him Bob mostly over at his house.” “Yeah,” one of the older women remarked, “I remember to this day now, I can hear Julia Willis calling off her porch, saying, ‘Bob, come on now.’ She called him Bob.”

They noticed the other name that came up at the end of the song: “Tell my friend, boy, Willie Brown.” That brought another whoop and shout of recognition. Robert Johnson hadn’t sung about the places where he was raised and lived, but he had sent a sly message back home. He’d named the local musician who was probably the largest single influence of his life in terms of craftsmanship, style, and companionship. He’d sent him a nod of recognition and thanks. “You can run, tell my friend, boy, Willie Brown, Lord, that I’m standing at the crossroad, babe, I believe I’m sinkin’ down.”

The name of Willie Brown brought forth another flurry of comments: How the youngster Robert had pestered Brown and other musicians, but especially Willie Brown, who was particularly sweet, gentle, and the “flat-out best guitar picker ever was around here.” He had taught Robert some things and then taken him around to play music. When the record was issued, Brown had nearly burst with pride. “He was more proud of this here song than he was of his own records,” one man said. Someone else said he never knew that Brown had made any records, and that triggered a round of arguing.

I had been holding the edge of the disc, letting the turntable grind away underneath it, so the next song wouldn’t prematurely cut off the remarks about Willie Brown. After they’d run their course, I let the record go and the next song—partly sung, partly talked and mumbled, punctuated by snapping bass strings—brought forth cheers of recognition. It was their favorite: “Terraplane Blues.”

Before it was half over, a number of the group asked me to play it again. And then they asked for it to be played a third time. Only after that did they want to hear the other songs, which met a varying reception. Some were enthusiastically greeted like old friends, but others were strange to them, pieces they’d never heard before and had never heard him sing. They decided they were likely songs he had created just for the records but had never sung anywhere else. One of the unfamiliar songs was the one most prized by many collectors, “Hellhound on My Trail,” although one man recalled, “I heard him do that piece a couple times, I think.” They all agreed, however, that the recording of it was unfamiliar.

When “Last Fair Deal Gone Down” came along, the listeners agreed that it was a song Johnson had been singing when he had first started playing the guitar. Derived from a work song, this song is the one that mentions the “Gulfport Island Road.” I asked whether anyone knew where that was. People shrugged. Someone said, “Not around here,” and someone else said, “Have to be down by Gulfport, I expect.” No one knew anything of Johnson’s being exactly there, but they agreed that he was always going “up to Memphis” or “down the country somewhere.”

“Preaching Blues” started another small dispute. One man said the recording was “different from the way I knew him to sing it,” while another said he had heard Johnson sing it exactly like the recording. The first man said the song was supposed to have “something different” in it. He asked me to stop the record a minute, and then he quoted a fragment of a line he recalled: “I know my friends are blind, my enemies see right through a door.” No one else recalled hearing him sing that line; it doesn’t appear on any of the recordings. The dispute dissolved in some laughter regarding the last line of the song, which mentions “going to the ’stillery.” The men exchanged a few remarks about the distillery that used to stand in the bottoms. The women frowned and hushed them.

It was hard to know how much to trust any particular comment. The group said that “Hellhound on My Trail” was unfamiliar, yet when I quoted a line from it, nearly all agreed that they’d heard him sing that line. And while some of the recordings were “strange,” some of the selections that had lain in Columbia’s vaults for twenty-five years were familiar. They knew the words to “If I Had Possession over Judgment Day.” One man finished the opening verse, anticipating the singer, saying the words aloud, “then the women I’m loving wouldn’t have no right to pray.” Someone else answered it, “Yeah, Lord, that’s it! That’s the way!”

During that evening in the Smiths’ house, countless memories were stirred by the old recordings. On the previous days people had talked, responding mostly to specific questions, but now they were chatting among themselves, remembering things, piling their thoughts together. Some of them seemed to recall a youngster who had never found the easing of tensions and pressures that usually comes when a boy turns into an adult. He remained “hot-blooded and full of piss.” He was like a kid who risks his life on a dare: they compared him to another boy who had died taking chances with a moving freight train. Robert remained fundamentally restless, unmanageable, full of passion, and anxious about satisfying it.

Several times the same remark was made: “Robert’s trouble was women, mostly.” Others would nod and agree. Someone said, “He never got past being young.” The picture they drew was a cliché: a Delta Romeo, blinded by passion at the age of fourteen, unstrung by tenderness and lust for his Juliette. But Robert’s tragic flaw was somewhat wider and deeper; he would experience his passion and unstringing time and again, as different women and different places would attract him. It is difficult to imagine Romeo setting up conventional housekeeping with Juliette, and in the same way—except for the one time he did settle down. Although seemingly a mild, easygoing person, he was full of thoughts that provoked him.

“If you ever spent much time with Robert,” one woman said, “you’d know what I mean better. I mean if you’d be with him hour after hour, for a whole day, you’d know. He’d be just as easygoing as anyone, then he’d get quiet, and didn’t answer back if you talked to him. Next time you look, he’d be moving his lips, talking to himself, saying things to himself about what had happened, and the more he talked the more he got upset. Then he’d just sit and be still for a long time, thinking. Then, next, all of a sudden he’d be joshing with you, or he’d want something to eat.”

Odds and ends of the memories were just details, but they added color to the picture. He dressed poorly, wore work clothes, and seldom made himself out to be the kind of well-dressed sport that musicians often were. His father had died when he was young and that disturbed him. He never accepted Dusty Willis as anything but a foolish old man his mother had taken in.

He listened to the radio a lot and would favor hanging around those houses that had a good set. He’d listen to anything: Amos ’n’ Andy, the Grand Ole Opry, soap operas, news programs, or “that big dance orchestra that used to come outta a big hotel over in Hot Springs, Arkansas.”

He traveled a lot, but usually not great distances, and mostly in a north–south line up and down the Delta: on the Mississippi side, on the Arkansas side, over into the Louisiana side, but not too far over. Often he would go to Memphis and occasionally up further, maybe to St. Louis. He would come back saying he’d ridden the Greyhound from Vicksburg or had caught a ride out of Clarksdale or ridden the ferry over from Helena.

When I told them that it was almost impossible to locate people in any of those towns who remembered him, Phax Long explained: “I tell you about Robert, he wasn’t any big personality like a lot of musicians you see. Some of those guys had a sign on their hat or a sign on their guitar telling who they was, and they’d advertise themselves like, and they’d spend the evening doing things to make the people notice them. Well, Robert, he wasn’t like that. That wasn’t his way. His music was what he did, and he didn’t do nothing else to impress himself on people.

“You know, lots of times a person might go to a place and hear the music, but he might never look at the man who’s making it. The music would be off in some corner, and maybe people standing in the way might keep him from seeing. And even if he did see him, he might be busy with something else and might not get to know him—because Robert never did nothing to impress himself. He wasn’t no big personality.”

They described a slender young man, inconspicuous except for his guitar and his recklessly bold manner around some women, hitchhiking around the Delta, knowing dozens of different plantations, moving in and out of a few cities, moody and self-effacing, looking shyly, then more directly at a woman whose face was new, leaning over to pull her out of a crowd and saying, “You sit by me, hear?” and never fazed when someone pointed out the woman’s husband. He’d simply say, with the boldness of kids playing chicken on the highway, “Damn that man, girl. Damn that man. You come sit here.”

Yet he would avoid violence and make a quick pretense of yielding whenever he was threatened. Then the next day, when the husband was off at work, Robert would show up at his house, slipping quickly in the kitchen door to see his latest admirer.

“It’s amazing to me he lived as long as he did,” one man concluded. “Considering the risks he took, and the way he was, he lived longer than he had a right to expect.”

A quick reference was made to a particular incident that had happened in a house only a few doors away: “He could have got killed that time.” A woman spoke up with a raw sound of jealousy, even after all the years that had gone by. “And for what? That old thing that used to live there?” She looked indignant. “Robert didn’t have good sense sometimes.”

An older man spoke up and cut her off: “I don’t think more needs to be said about that.” He shook his finger at her. “Speak no ill of the dead.”

The conversation turned to lighter things. Curiously, one insignificant detail had fallen into place. One of the men there had ridden along to Hernando one time when Robert had gotten someone to drive him there to catch an Illinois Central train. They’d gone in a used Model T Ford, bought about 1927 or 1928. It was a hellish trip over unimproved roads, muddy from recent rains, and Robert would have missed the train if the train itself had not been late. The man thought Robert had gone there several times to catch the southbound train, which could put him in Hazlehurst in an hour. The group pointed out that there wouldn’t have been any need to catch a northbound train, since it only went to Memphis, and he could get a Memphis train in Robinsonville.

In time the listeners’ focus shifted from the surprise of hearing Johnson’s old songs to enjoying them once again, and the mood changed; I could feel a kind of tension and an emotional charge. The Robinsonville neighbors made up a fair sampling of the kind of audience that the blues tradition had served. They showed no particular solemnity in the way they listened to blues. They listened closely in some spots, but at other times they nodded or shook to the music, enjoying it but making no special issue of it until a particular phrase grabbed them, when they would shout or bark “Yeah!” as if they were hearing a stirring sermon. They would say the words along with the song, or echo choice phrases just afterward. They frequently laughed with recognition or surprise as the music rolled on, even at Johnson’s more brooding, dark sentiments. Even the darkest of them were listened to with a sense of exuberance—perhaps as release and an outlet for the emotions they evoked.

There’s no need to take the blues too seriously when it is totally familiar. A question sometimes arises to whether the more intense of the bluesmen—Bukka White and Robert Johnson and Son House—were indeed the kind of musicians who played primarily for dances. It is not obviously dance music in the sense that many blues are. Such a question doesn’t really arise in the circumstances in which they performed, or even in this re-creation of earlier listening, with people gathered round a phonograph. They listen. They hear the poetry. They observe and take note. They respond. They drink beer and they argue and they hassle among themselves and they go in back to relieve themselves and they come back to dance or ease in on some woman. The women hear and they move and they light up the shadowed rooms. They lend the music a click of jewelry and an odor of heat. They listen to the poetry. They hear the music. It flows in and it flows back out. They react. They respond. It’s a total situation. A single song may gain hushed silent listening. Another may mingle with the rattle of bottles and noise of the crowd. There’s no set rule. They dance. They react. They argue and talk over the music and get half-drunk and thirty years later they know the songs so well they can phrase the words right with the singer. They absorbed it all—the man himself and his music—totally, because it was theirs. For them, the blues was never meant to be taken seriously or reflectively. It was simply a force, expressing the deepest roots of their lives.

During that evening I finally caught a glimpse of Robert Johnson. The dusty red album cover by Burt Goldblatt helped. I don’t know how I’d evaluate it objectively as a work of art, but it reflected considerable insight and inspiration. “Blues ain’t nothing but a lowdown shaking chill,” as Son House sang. Goldblatt had captured a glimpse of Johnson somehow—possibly a better glimpse than mine, because he had gotten it wholly and entirely from listening to the recordings. I had to stumble over half of Mississippi, wind up here, get all these people together, and then—maybe for the first time—really listen to Johnson’s music.

I sat off to the side, one hand holding the album jacket, leaning back, absorbing, trying to hear Johnson’s songs with their ears and their memories. I was staring aimlessly at the cover itself, not looking at it but watching it. Goldblatt had used a high angle to look down on the scene, and he had matched Robert’s figure with one of his shadow, cast on the floor by his feet as if by some single hard light. And there was another shadow, not on the original painting but on the jacket, just at that moment, of a dancer moving in the same hard light. There were shadows of people hunched together, engaged with the music or engaged with themselves or their partners. There were also shadows of another guitar player, off to the side. Occasionally the two musicians would lean together and exchange a pleasurable passage. At other times the older man—heavyset, sitting more upright—would lean away from the hunched youngster in the striped shirt. “Well, now she’s been sucking some other man’s bull calf, oooh, in the same man’s town,” I could hear Johnson intone. The younger man had something shiny—a tube of metal or a bit of glass—slipped over the end of one finger, and it made a blurred place in the picture. At times his entire arm would blur during a particular passage. The voice knifed and cut the noise with no trouble. Often it was keen and knotted, sometimes a little more relaxed, deepened.

“Me and the devil were walking side by side,” he sang. He paid little attention to the crowd, sometimes exchanging a word or two with the people who surrounded him but mostly maintaining a private world, shared only in part with the older musician who sat off at his side. They seemed indifferent to the way the crowd reacted. There was no sense of compulsion: listen, or don’t listen, They were unaffected by the swirl of noise and distraction, and yet they commanded it. The pulse of the music could bring the whole crowd to silence. A single line could stun the room. Occasionally Johnson would let it ride, falling into some of the older songs, playing a few casual pieces, and then tightening up over the guitar and soaring, for just a moment, into a falsetto. Or he’d stun his listeners with the simplicity of a thought or the pleasure of an idea: “All I would need is my little sweet rider just to pass the time away.” I saw him lift his head an inch, but not enough to see his face.

The record ended, and that broke the spell. I played it over again, but the next time the album jacket stayed as Goldblatt had designed it. I experienced no further hallucinations, although the listeners in the room remained deeply connected. I wrote furiously, jotting down what people said, trying to catch as much as I could, shuddering at the thought of the job I would have when I got back home. The Robinsonville visit had given me dozens of pages of notes and comments, and countless leads and thoughts as to how to pursue other musicians or members of Johnson’s family. After a while, writer’s cramp set in, and I relaxed and settled back, listening again.

This time my thoughts were more objective. I remembered what Alex Clark had said about plantations near Memphis creating the biggest problems for landowners. The closer they were to Memphis, the harder it was to keep workers on the property; the more efforts the landlord would need to make; the more entertainment he’d have to offer to compete with the allure of the city, its jobs, and its excitements. The demand for musicians and the strength of the blues tradition increased in proportion to the proximity of other temptations. The nearness of Memphis might explain why there was such a richness of music in Tunica and DeSoto Counties. Not only in the Delta but in the land to the east, the farms in the hills, but still near Memphis, near enough to make it tough to keep people from its draw. Willie Brown, Charley Patton, Son House, and Robert Johnson had all thrived here. In Beat 1. The theory doesn’t fit or explain other places where musicians concentrated, but it’s supported by the parallel events across the river in the Delta near Memphis. To this day Hughes, Arkansas—only twelve crow-flight miles from Robinsonville—is still such a center of taverns and music. Obviously no one factor explains anything. It only helps.

Indeed, Memphis ranked as one of America’s most extraordinary centers of music in the interwar years. It supported innumerable street minstrels and party house guitar players and pianists. And there were the jug bands of Memphis, plus medicine show dancers, skiffle dancers, and the formally trained musicians who played in theater orchestras and dance bands. Few cities could claim such a heritage, and Memphis offered the young Robert Johnson a chance to hear distinctive stylists such as Furry Lewis, Robert Wilkins, Hambone Willie Newbern, Sleepy John Estes, and Frank Stokes.

It’s illuminating to consider Johnson’s musical education in terms of the places where he grew up. He had been born and partly raised where Tommy Johnson and his brothers lived. He had lived in Beat 1, Tunica County, with the richest of the older musicians for him to follow. He had lived both as a child and as a teenager in Memphis and heard what it had to offer. He had thus availed himself of the area’s great centers of learning, although it seems to have occurred not by design, but by chance of birth and accident of residence.

This is not to suggest that clear-cut traces of these various teachers can be found in Johnson’s work. The influence wasn’t of that kind or shape. He shared their traditions and many of their general concepts. But essentially the older generation taught him fundamentals, gave him tools, inspired his own efforts, and set him an example to match.

Curiously enough, when he was derivative—and the recordings include some fairly obvious examples where he sings or plays imitatively—it was often something from records he had heard, by musicians he probably never knew or met. But of course he traveled in a world in which recordings by Leroy Carr, Lonnie Johnson, and Blind Lemon Jefferson were an established part of the musical spectrum. The raggedy local musicians at the crossroads store and the records wobbling around on wind-up phonographs were equal and inseparable elements in the ears of those who grew up in that generation. There were, of course, specific traits Johnson acquired from close associates: the clenched, compelling voice that Willie Brown and Charley Patton used, and the bottleneck slide guitar techniques that Son House favored, taken a step further.

Hearing Johnson’s recordings in the company of people who had known him generated a number of conflicting thoughts about the man. Minor disputes started up several times during the evening. The old-timers had a kind of possessiveness about their memories, and they had to wrangle a bit to determine who was more correct or in agreement with the others. The second or third time it was played, “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” started an argument. Phax Long said the song ought to have another verse or line about “She oughta be buried alive.” (It may have had such language one time; it was a commonplace phrase. Yet Johnson seems to have avoided the commonplace in the songs he recorded, so it’s likely he dropped it for something more original). Long was insistent that the record “didn’t have it right.” But Alex Clark was equally insistent that he had heard Robert sing the song exactly like it was on the recording. That remark needs a grain of salt to go with. It’s probably impossible for anyone to know whether it was exactly as he heard it from Robert or exactly as he heard it from the same record, thirty years ago.

Someone else said he thought the phrase in question belonged in a different song. And another person quite properly pointed out that Johnson might have used the same line in several different songs. That remark deepened the dispute. “No,” Clark said, “he was careful about putting his songs together just the certain way he wanted them to go.”

“Still and all, he’d have to change it around some,” Long answered.

“Well, that record is right. That’s just the way he sung it, and I remember him singing it over across there”—Clark paused to point his arm and mumbled some name indistinctly—“where that sugar shack used to stand.”

“I don’t know about that. I just heard him sing it different.”

The phrases of other songs passed by, some studied and argued about, some ignored, and some anticipated before the singer actually got them out. At times there was a round of “Hush!” and a shushing of the talkers, and the whole room would concentrate on the moods of the songs and the tense, compulsive guitar that gave them such uncanny emphasis. There was some kind of reaction to almost every phrase: “Worried blues, give me your right hand.” Nods of recognition and a smile. “Watch your close friend, baby, then your enemies can’t do you no harm.” A grunt and an exchange of glances; an incident remembered, perhaps. “I have a bird to whistle, and I have a bird to sing.” Smiles of pleasure and heads turning to look at the other people. “Best come on back to Friars Point, mama, and barrelhouse all night long.” Chuckles, a mixture of huhs!, some shushing at a bawdy remark, and a little trailing-away laughter. “She got a mortgage on my body now and a lien on my soul.” A sniff of disapproval lost in something mumbled, and a grunt of agreement. “You may bury my body, oooh, down by the highway side.” Another grunt. “So my old evil spirit can get a Greyhound bus and ride.”

The room eventually grew still, and the lines were greeted by little more than a mumble or a nod. Occasionally there was a comment, but mostly it was a private aside. Finally someone broke into the spell. He said, “About Robert—he had a way of making up a song that makes you wonder.”

A man who had known Johnson as a teenager, a man who hadn’t had much to say before now, said, “He was maybe only a few months different in age from me, but you know he was always into things, moving, and going too fast.”

“How do you mean?” one of the others asked.

“Well, it’s there in the songs for you to hear it.” He pushed a calloused thumb at the phonograph. “He was always like that. He was dying faster’n he was living.”

Another dispute started. Someone argued that they had known Johnson most of his life, and he was nothing like that: “He was just an ordinary kind of guy, except he had this talent for music.”

“Listen at what he’s singin’ there, man. Listen!”

More phrases went rushing by, and some wanted to hear certain songs over again, so the sequence was interrupted until finally the record played through again to the last song, the one they said they had never heard before. “I got to keep moving, I got to keep moving, blues falling down like hail, blues falling down like hail.” The voice was now a cry, desperate and wretched. “And the day keeps on worrying me. There’s a hellhound on my trail.” The phrase was repeated. “Hellhound on my trail, hellhound on my trail.”

The listeners shuffled about, now silent, but ready to argue some more about the man who had created such haunting songs and left them behind in these few mysterious recordings.

Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey is now available to purchase through Smithsonian Books. Originally compiled and written by Robert McCormick, this edition is edited by John W. Troutman. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey, © 2023 by Robert McCormick