NATIONAL ZOO AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGY INSTITUTE

2019’s Conservation Stories Worth Celebrating

Saving species is what we strive to do every day at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. As the year winds down, we’re reflecting on some of our biggest conservation success stories of 2019.

Saving species is what we strive to do every day at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. As the year winds down, we’re reflecting on some of our biggest conservation success stories of 2019.

Bringing up babies

The birth of a threatened or endangered animal is always reason to celebrate, and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute welcomed many new faces this year. A tiny egg nestled in an incubator began wiggling and cracking April 22. Soon after, a Guam kingfisher emerged. This brightly colored bird is one of the most endangered on the planet. Guam kingfishers are extinct in the wild, and only about 140 of them live in human care.

The small beak of a hooded crane broke through its shell June 12, and with a little help from keepers, the chick emerged from its egg bright, alert and responsive. It was the second hooded crane ever born at SCBI. Later that night, an endangered red panda cub also arrived.

In June and July, the herd of scimitar-horned oryx grew by five. Scimitar-horned oryx were extinct in the wild until 2016 when the Environment Agency–Abu Dhabi (EAD) and the government of Chad started releasing oryx born in human care to the wild. Approximately 100 oryx now live in the wild since reintroductions began. SCBI ecologists are collecting behavioral data on the reintroduced oryx from satellite collars.

Keepers also celebrated the birth of two kiwi chicks this year – the first in January and the second in March. The Zoo was the first to hatch a kiwi outside of New Zealand in 1975 and participates in a brown kiwi species survival plan, which coordinates breeding efforts among zoos to build a genetically healthy population of brown kiwi in human care.

Just add water: a new proof-of-concept for tissue preservation

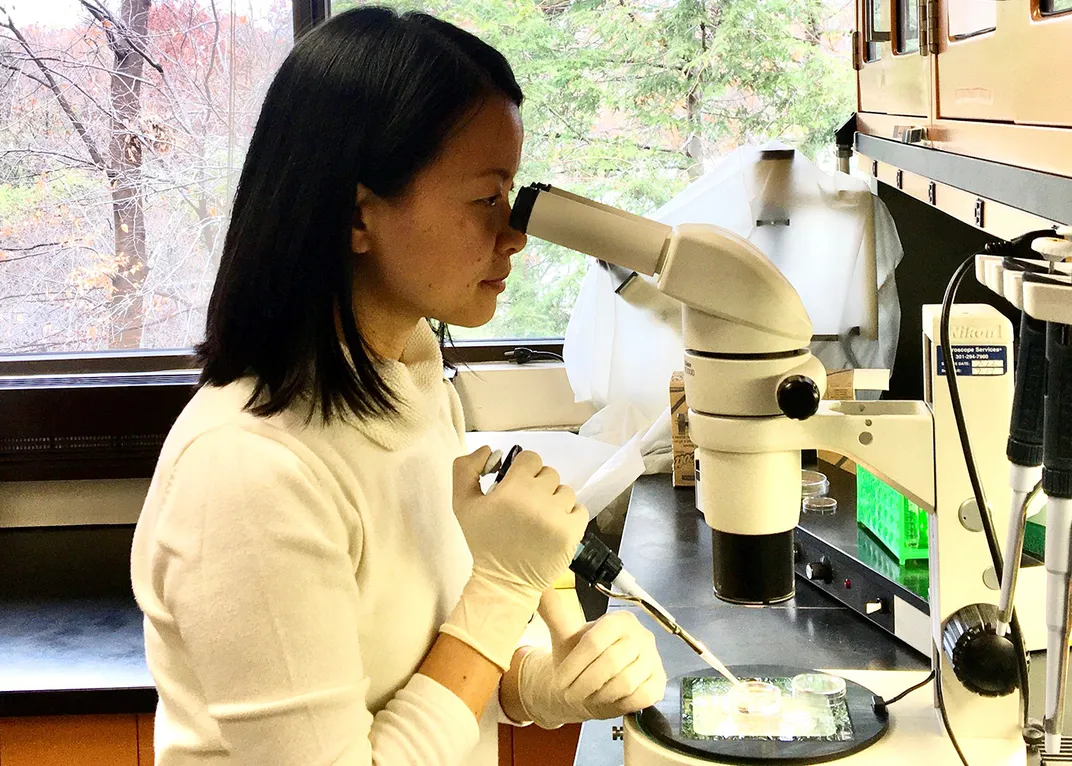

With the help of sugar and a microwave, Smithsonian scientists successfully preserved living ovarian tissues from cats above freezing temperatures. They adapted the concept from invertebrates (like brine shrimp) that survive dry conditions by flooding their cells with trehalose, a type of sugar. The sugar forms a stable, protective glass within and around the cells, preserving them until water is reintroduced.

Researchers infused ovarian tissues from cats with trehalose, then slowly dried the tissues using a microwave. They stored the dried tissues in a standard refrigerator for about a day, and then revived them by adding water. The rehydrated tissues maintained their structure and basic functions, including DNA transcription (a basic but important cellular process).

Scientists have been storing living biomaterials (eggs, embryos, sperm and gonadal tissues) for decades using cryopreservation, which involves freezing them in liquid nitrogen or special freezers. But it’s an expensive and resource-intensive process. This study is the first to show that dehydrating living ovarian tissues for long-term storage at room temperatures is possible. With this initial proof of concept achieved, the team is shifting their focus toward refining their techniques and improving tissue resilience.

If samples can be dried and stored this way, scientists around the world could more easily preserve reproductive tissues and support wildlife conservation. Their findings could also one day help human patients by providing a less expensive and more convenient method of storing ovarian tissues for procedures like in vitro fertilization.

The Next Chapter in Giant Panda Conservation

Giant panda fans far and wide said a bittersweet goodbye to Bei Bei in November. As part of the cooperative breeding program with the China Wildlife Conservation Association, all giant panda cubs born at the Zoo move to China when they turn 4 years old. The majority of giant pandas under human care live in China, and the best genetic matches for Bei Bei to breed with as an adult live at the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda’s (CCRCHP) bases.

After a week of farewell celebrations, the 4-year-old panda boarded a nonstop flight to China and has since settled in to his new home at the Bifengxia panda base.

Flowers and forest health

In July, citizen scientists working with SCBI discovered a rare purple fringeless orchid (Platanthera peramoena). This flower is nearly extinct in the commonwealth of Virginia, where it’s estimated that fewer than 1,000 remain.

Purple fringeless orchids need wet soil to grow and are in decline throughout their range, where wetlands have disappeared. The citizen scientists found four purple fringeless orchids in bloom during their routine survey on a private farm. The orchid surveys are part of a pilot program exploring the potential for orchid species diversity and abundance to serve as an indicator of forest health.

An unexpected arrival at Reptile Discovery Center

Life found a way at the Zoo when a female Asian water dragon underwent facultative parthenogenesis. That is, she gave birth to a healthy, thriving offspring despite never breeding with a male or receiving genetic material.

Smithsonian scientists were the first to confirm parthenogenesis in Asian water dragons and published their findings in June.

Banding together for birds

Conservation is all about collaboration. This year, researchers across the country came together to publish a study revealing a massive decline in bird populations — nearly 3 billion birds lost since 1970. While the news of such a significant loss could be discouraging, the prevailing message from the study’s authors is one of hope. We have an opportunity to take action on behalf of birds, and together, we can help bring them back.

Two shining examples of how conservation action can help save species are the Guam rail and the Kirtland’s warbler. Guam rails lived on the Pacific island of Guam until the accidental introduction of the brown tree snake near the end of World War II drove them to extinction. About 10,000 of these birds likely roamed the island before snakes arrived. By 1985, only 21 Guam rails were left. The birds were captured to begin a breeding and recovery program.

The SCBI’s Guam rail breeding program began in 1985 and continues today. Researchers work with the Guam Department of Aquatic Wildlife and Resources to repatriate the birds to Guam for reintroduction to the wild on the island of Rota.

This year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature declared that Guam rails are no longer extinct in the wild. They are only the second bird to ever recover from extinction in the wild and are now reclassified as critically endangered.

Endangered Kirtland’s warblers have long been plagued by brown-headed cowbirds at their summer nesting grounds in Michigan. The parasitic cowbirds lay their eggs in warbler nests, causing warbler parents to care for the cowbirds rather than their own chicks.

By 1971, only 200 male Kirtland’s warblers remained in the wild, and about 70% of their nests were parasitized by cowbirds. For 40 years, conservation efforts have targeted brown-headed cowbirds to prevent them from laying eggs in warbler nests. A study published by Smithsonian scientists in July found that Kirtland’s warblers may no longer need protection from cowbirds in Michigan.

Hide and seek: an inventive way to track down wood turtles

Finding a turtle in a forest can feel a lot like searching for a needle in a haystack, but Smithsonian researchers found a high-tech shortcut that makes searching for wood turtles easier and cheaper. It’s called environmental DNA, or eDNA.

Scientists collected water samples from streams where wood turtles might live. Then, they used a very sensitive filter to look for eDNA from biological traces that wood turtles leave behind – like feces, urine, shed skin secretions and fertilized eggs. They found bits of wood turtle DNA in samples from 17 different streams. Researchers visited those streams to confirm the accuracy of their results and found wood turtles in each area that eDNA indicated they were living.

Wood turtles are endangered and elusive. It can take years to become good at finding them in the wild, and training researchers and managers to find them is expensive. This new eDNA survey method is easier, cheaper and could one day allow scientists to track wood turtle distribution in real time.

What’s better than a clouded leopard cub? Two clouded leopard cubs

Playful, curious clouded leopard cubs Jilian and Paitoon stole visitors’ hearts when they debuted at the Zoo earlier this year, but these two cubs are more than cute. They’re also a reminder of the important conservation work that happens here every day.

Smithsonian scientists have been in the business of clouded leopard conservation for decades, studying their behavior, biology and ecology. One of their research focuses has been creating assisted reproductive technologies to help the species.

In 1992, SCBI reproductive biologist JoGayle Howard became the first scientist to perform a successful artificial insemination in clouded leopards. Twenty-three years later, SCBI scientists built upon her legacy when they performed a second successful artificial insemination using a new technique that required fewer sperm cells.

In 2017, they again made history with a third successful artificial insemination, this time using frozen sperm on a female leopard named Tula at the Nashville Zoo. The resulting cub, Niran, gave birth to Jilian — one of the cubs now living here at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. These three generations of clouded leopards are living proof that conservation science can help save species.

Stay with us in 2020 as we continue our work to save species and celebrate Smithsonian’s Year of Earth Optimism with even more conservation success stories.