NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

How WWII Service Members Helped Shape the Smithsonian’s New Fossil Hall

World War II service members played an important role in the shift toward audience-centric storytelling in the new “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils - Deep Time.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Postcard.jpg)

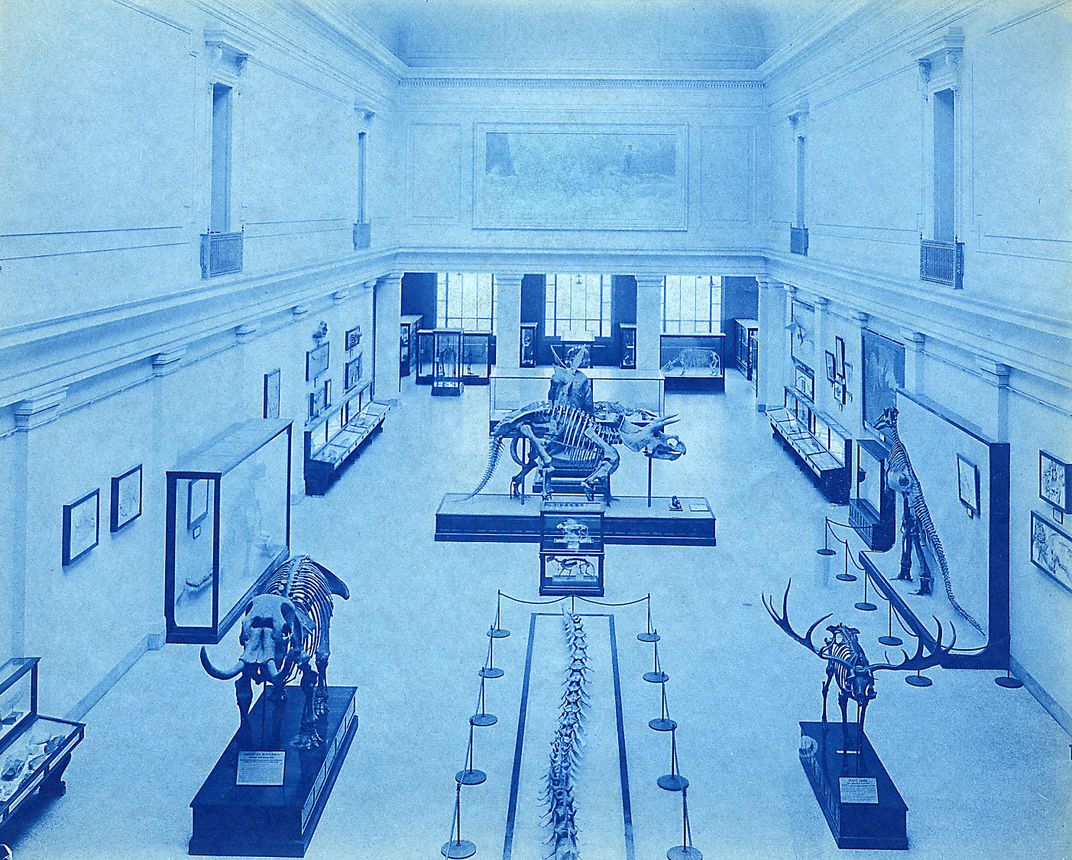

If you were to visit the Smithsonian’s fossil hall (affectionately known as the “Hall of Extinct Monsters”) from its opening in 1911 up until the 1940s, you would see large mounted fossils occupying a central, sky lighted hall of vertebrates. On either side of these massive skeletons were two galleries flanked by mahogany cases that contained fossil invertebrates and plants.

While the big fossil mounts would have seemed just as flashy to early 20th century audiences as they do today, much of the other collections were displayed in a style rarely seen in contemporary museums. Small specimens occupied simple cases organized by museum experts to emphasize scientific information. Curators wanted to highlight specimens’ size, region, or biological relationships -- and chose fossils to convey information, regardless of how they looked. Researchers arranged specimens into groups and labeled them accordingly. Labels were simple: a specimen name, a locality, a brief scientific description.

Today, museum labels are a whole genre of design and storytelling. As the new “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils--Deep Time” exhibit writing team wrote in the National Museum of Natural History’s blog, modern labels “pique our visitors’ curiosity about the natural world through engaging stories, compelling experiences and plain language.”But the move toward audience-centric storytelling did not happen overnight. Smithsonian reports from the 1940s suggest that feedback from military service members during World War II played an important role in that shift.

After the United States’ entry into WWII, the Smithsonian saw overall decreases in visitorship, but major increases to its local visitors. A rubber shortage and the rationing of gasoline limited travel so more residents from the crowded Washington, D.C. area came to the U.S. National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History building). When Sunday hours were increased from half days to full in 1942, service men and women on weekend furloughs came in droves. A year later, the museum organized free guided tours of the museum for service members. Every 15 minutes from 11 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. on Sundays, tour guides took small groups of uniformed personnel for a 45-minute tour through the museum. More than 5300 service members visited the galleries from October to June 1944.

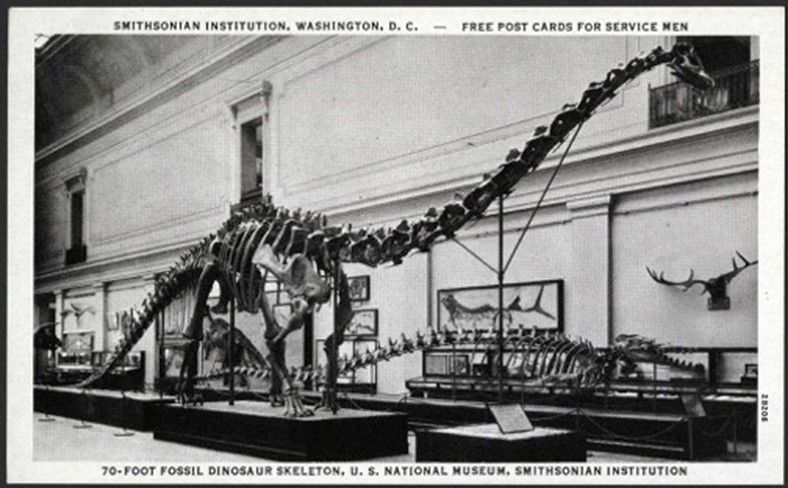

The museum also created and distributed almost 2500 welcome packets and gave service men and women free magazines that year. Across the National Mall at the Arts and Industries Building, uniformed visitors received free postcards of the Smithsonian. By January 1944, the Smithsonian ran out of all 300,000 cards it produced.

At the peak of the war, nearly half of the museum’s more than 1.5 million annual visitors were service men and women—many with minimal formal education. General reports from the museum hint that these new visitors offered critical feedback on the exhibits. One, for instance, noted that “many interesting and worth-while reactions were obtained, as indicated by the questions asked and the interest expressed concerning the various exhibition halls.” But the museum’s paleontologists and geologists got a clearer message. These new visitors expressed such a strong desire for clearer explanations that the staff began to take their advice:

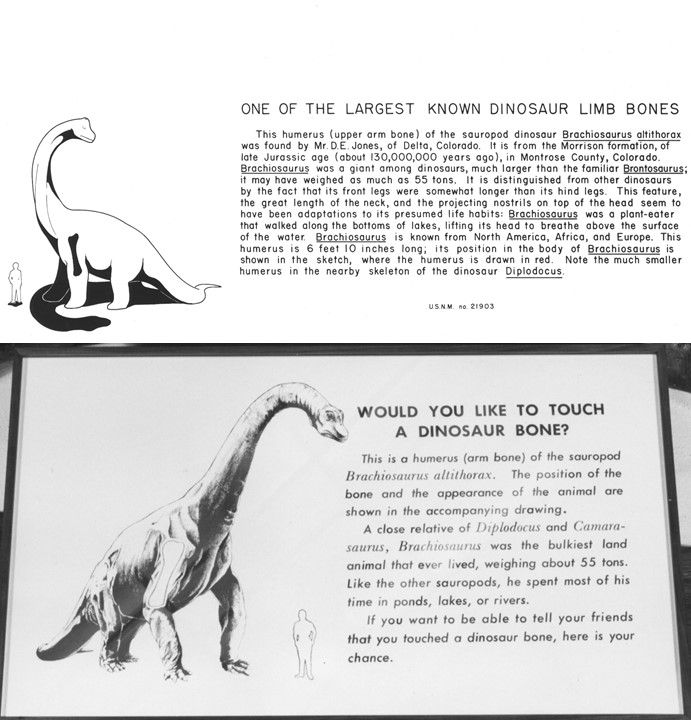

The many visiting servicemen, representing a clear-cut cross section of American life, have been so frank in their questions and remarks on the exhibits that much of value for future work has been learned. Their comments have been of particular value in revealing the most appealing type of exhibition label, namely, a placard explaining in several lines of rather large black type the essential features of each display case.

This feedback was the first anyone in the museum received from visitors who weren’t frequent museum-goers. It inspired the paleontology staff to rearrange the fossil displays in what they called a “more logical arrangement” and became part of what drove the museum to hire its first professional editor, Joseph G. Weiner, to shift the tone of labels from didactic to more accessible and inviting prose.

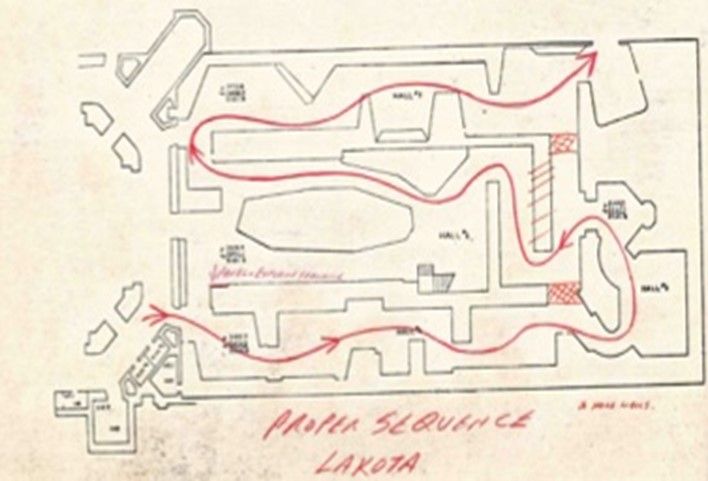

Improvements to the visitor experience in the fossil hall culminated in a major renovation that followed. In the redesign of the “Mad Men” era, and as part of a wider Smithsonian effort to modernize exhibits, the museum hired two professional designers—Ann Karras and Barbara Craig—who led the charge in designing narrative pathways that guided visitors chronologically through the fossil hall.

Since the 1960s renovation, the process for writing labels and designing museum spaces has continued to become increasingly story-driven and audience-focused. Experts in education, writing, graphic design, project management, and a range of other now-bonafide museum fields specialize in designing holistic experiences for the public. Audience and educational research now test ideas and text with visitors long before they finalize the content.

In the new “David H Koch Hall of Fossils—Deep Time,” every piece of text has been carefully edited (and edited, and edited!) by curators, educators and professional exhibit writers with diverse audiences in mind. That careful process allows the Smithsonian’s new fossil hall to share the story of life on Earth in a scientifically accurate yet accessible way. This Veterans Day, we can thank the “frank” service men and women of the 1940s for sparking positive change.