NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Can Technology Bring the Deep-Sea to You?

Telepresence adds a collaborative dynamic to scientific research, outreach, and education.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/july13-1-hires.jpg)

As an expert in deep-sea sea stars stationed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, I’ve conducted field work in some of the world’s most amazing places. I participated in at least two submersible dives in Hawaii and the Bahamas and trawled for specimens in the Antarctic and near the Aleutian Islands. In most cases, field work involves long trips under difficult circumstances to isolated and remote areas where communication with colleagues and the public is, at best, difficult and, at worst, impossible. But, last month I experienced a unique type of research at sea during which involvement of the scientific community and citizen scientists in deep-sea exploration was brought to interesting new levels!

From July 4 to August 4, I conducted fieldwork as part of the Laulima O Ka Moana expedition to map and survey the sea bottom of the Johnston Atoll region of the central Pacific Ocean. For nearly two and a half weeks, I produced live, continuous narration for a video broadcast and participated in several educational events including one which took place in the Sant Ocean Hall here at the National Museum of Natural History while aboard the Okeanos Explorer (OE).

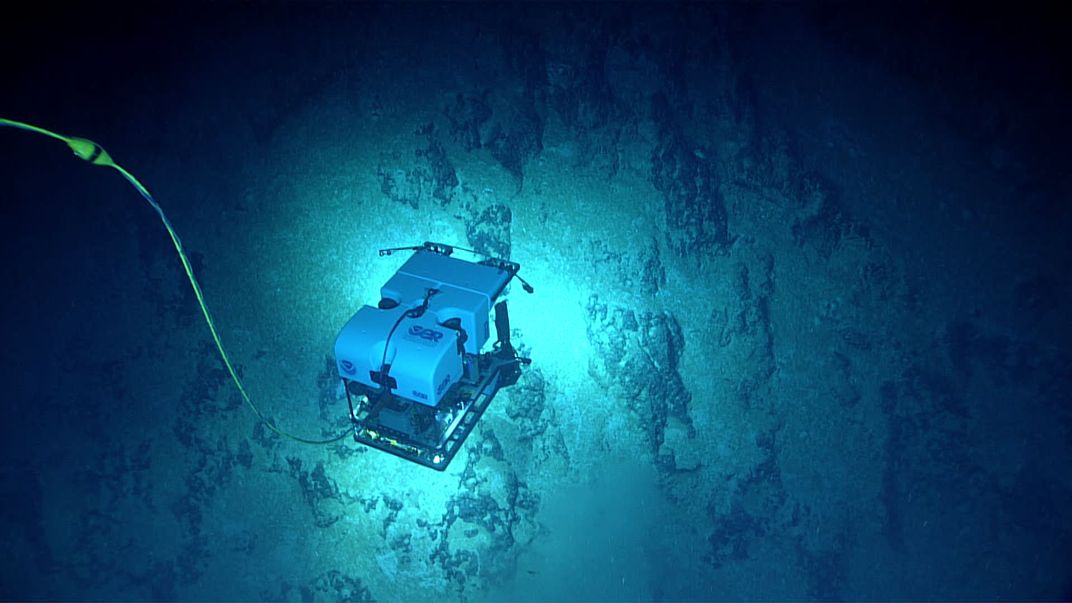

The OE is operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and is America’s premier ship of ocean exploration. It uses a remotely operated vehicle (ROV—basically a robotic submarine) about the size of a minivan equipped with floodlights and high definition cameras to help scientists survey the deep sea. But, the OE isn’t a conventional research vessel.

Perhaps its most unique capability is its connectivity which enables instant and convenient collaboration with the broader scientific community and citizen scientists. It broadcasts a high-definition video of the deep-sea from the ROV deployed off the ship (often more than 1000 meters below the ocean surface and sometimes as deep as 5000 meters) back to shore almost instantly. This allows those on the ship in the middle of the ocean to conveniently connect with practically any scientific expert anywhere through a telephone or internet connection. We regularly collaborated with a dedicated pool of scientists with expertise in ecology, marine archaeology, geology, conservation, and more via the live feed. These scientists could call in from different places around the world, ranging from the U.S., Russia, and Japan. In fact, until last month, I participated in OE as one of these “call in voices” to provide the name and scientific significance of sea stars being observed by the scientists aboard the ship. New species and/or new habitats are commonly encountered on these cruises making them a unique blend of research and education by allowing everyone instant access to the thrill of these discoveries!

The OE’s live video feed also allows citizen scientists to participate in the exploration. While I was on the ship, citizen scientists—out of their own interest—took screenshots of the live feed and shared them on Twitter (#Okeanos) and on Facebook (the Underwater Webcams Screenshot Sharing group). In doing so, they not only captured noteworthy images which later complemented those taken by the scientists aboard the ship, but also helped spread the word that even at its deepest depths, the ocean is home to a rich biodiversity of life.

For decades, I have traveled the world to study the deep-sea and witness remarkable forms of life. These experiences have often been too difficult—if not impossible—to share with the broader scientific community and the world in real time due to the nature of deep-sea field work. The Okeanos Explorer, however, allowed me to work with other scientists and the world via its unique connectivity. Ultimately, the OE’s telepresence capability adds a collaborative dynamic to scientific research, outreach, and, education that I hope will become more common to marine biology researchers at sea in the future.

Although I won’t be narrating it, the next Okeanos Explorer dive begins September 7th!