NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Thinking about the Indian Removal Act, at the National Archives Museum and National Museum of the American Indian

The Indian Removal Act, signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830, became for American Indians one of the most detrimental laws in U.S. history. Nation to Nation looks at Removal’s historic and legal repercussions for the tribes. The upcoming exhibition Americans, opening in the fall, will ask us to think about what we, as a nation, have chosen to know and not know about the Trail of Tears.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Removal_Act_at_the_National_Archives.jpg)

“Our cause is your own. It is the cause of liberty and justice.”

Principal Chief John Ross (Cherokee, 1790–1866), appearing before the U.S. Senate in 1836 to argue on behalf of the Cherokee Council against ratification of the Treaty of New Echota, ceding Cherokee lands to the United States

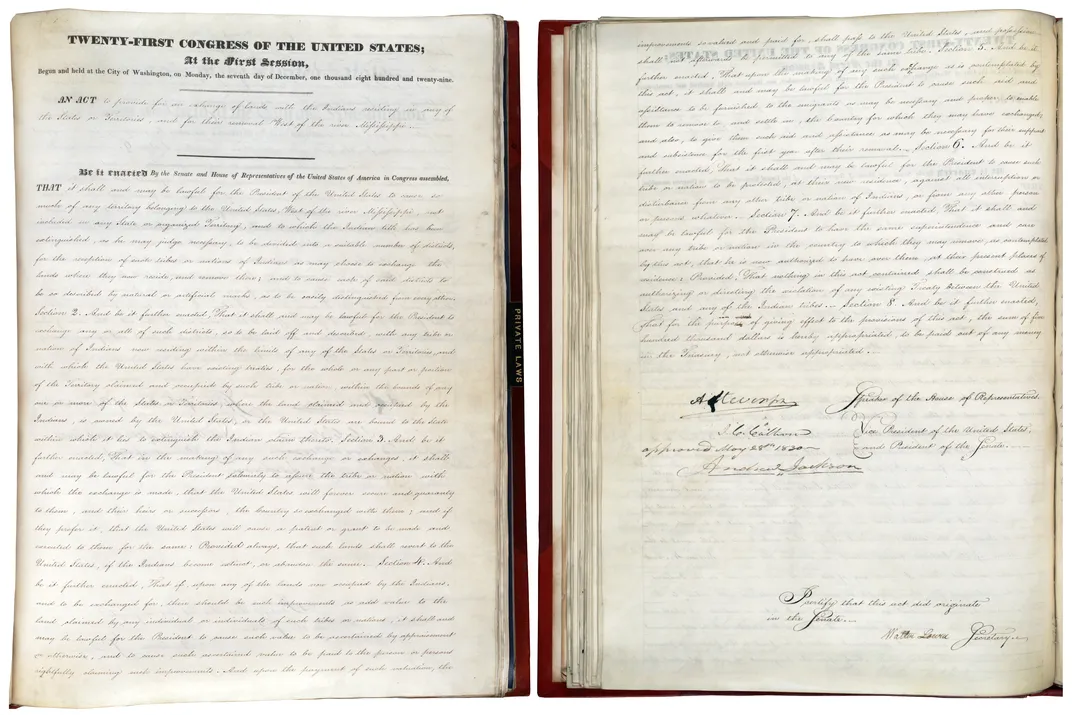

This spring, I visited the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C., to see the Indian Removal Act, on display in the Archives’ Landmark Document Case. Signed by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830, the Removal Act, gave the president the legal authority to remove Native people by force from their homelands east of the Mississippi to lands west of the Mississippi. It became for American Indians one of the most detrimental pieces of legislation in U.S. history. Under the Removal Act, the military forcibly relocated approximately 50,000 American Indians to Indian Territory, within the boundaries of the present-day state of Oklahoma.

At the National Museum of the American Indian, we address the importance of the Removal Act in two major exhibitions—Nation to Nation, which opened in September 2014 and will be on view through 2021, and Americans, opening October 26 of this year and on view through fall 2027.

“Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted. . . . And I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure. ”

Private John G. Burnett (1810–unknown), Captain Abraham McClellan’s Company, 2nd Regiment, 2nd Brigade, Mounted Volunteer Militia, account of the removal of the Cherokee, from a letter to his children written in 1890

Many Americans, and many people beyond the United States, know the story of removal—or part of the story. In the late 1830s, more than 20,000 Cherokee men, women, and children were removed from their homelands. Approximately one-fourth of these people died along the Trail of Tears—bayoneted, frozen to death, starved, or pushed beyond exhaustion. Less well known, perhaps, is that hundreds of other tribes shed tears as well as they were forced to leave their homes to make room for non-Indian settlement and ownership of their land. Through American expansion, every tribe lost land its people originally called home.

“They were not allowed to take any of their household stuff, but were compelled to leave as they were, with only the clothes which they had on. ”

—Wahnenauhi (Lucy Lowrey Hoyt Keys, Cherokee, 1831–1912), account of the Cherokee removal written in 1889, published by the Smithsonian Bureau of American Ethnology in Bulletin 196, Anthropological Papers, No. 77

The museum’s exhibitions look at the Removal Act from the broader perspective of events at the time it was enacted and during the nearly two centuries since. In the companion book to Nation to Nation, Robert N. Clinton, Foundation Professor of Law at the Sandra Day O’Connor School of Law at Arizona State University, describes the growing sense of national strength that allowed the federal government to move away from conducting negotiations with Indian nations as a sort of diplomacy—based on transnational law, mutual interests, and tribal sovereignty—and toward the direct pursuit of its one-sided goals:

The War of 1812 eliminated the possibility of Indian alliances with Britain, which had posed a threat to the stability and security of the United States. Thereafter . . . the bargaining power in treaty discussions shifted greatly to the United States, and policy was increasingly dictated by the federal government. . . . After a decade of treaty negotiations on the subject, the southeastern states provoked a controversy over the continued presence of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muskogee (Creek), Choctaw, and Seminole nations on lands within state borders. Congress decided to chart the policy unilaterally by adopting the Removal Act of 1830.

Nation to Nation also explores the place of the Removal Act in U.S. legal history. The exhibition shows how advocates and Native and non-Native opponents of removal battled in Congress and the courts—all the way to the Supreme Court—at the same time tribal leaders were working to ensure the survival of their people.

Americans, which will explore Indians and the development of America's national consciousness through four iconic events—Thanksgiving, the life of Pocahontas, the Trail of Tears, and the Battle of Little Bighorn—widens the museum’s perspective on the Removal Act even more. In developing the themes of the new exhibition, lead curator Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche) and co-curator Cécile R. Ganteaume wrote:

Democracy at the Crossroads—the section of Americans about the Trail of Tears—explores the contemporary relevance of removal and why it is still embedded in 21st-century American life. We focus on crucial elements of the history that usually do not receive the attention they deserve: A vigorous national debate over removal consumed the United States before passage of the Indian Removal Act. With the eyes of the Western world upon them, members of Congress cloaked the Removal Act in humanitarian language. The actual removal of Native nations from the South across the Mississippi was a massive national project that required the full force of the federal bureaucracy to accomplish. Finally, it is due to efforts of young Cherokees in the early 20th century that the expression “trail of tears” has come to be known throughout the country, if not the world, to represent a gross miscarriage of justice.

In the central space that links the four iconic events in Americans, visitors will find themselves surrounded by photographs and commercial art. The idea is to show how images of Indians—and Native names and words from Native languages—are and have always been everywhere around us in the United States. Once we look, we can see them as national symbols on monuments, coins, and stamps; in the marketing of just about anything you can think of; in the Defense Department’s naming conventions for weapons; and as part of pop culture. The reality of images and references to Indians everywhere is illustrated, for the time being, by the 1948 Indian Chief motorcycle on view in the museum’s atrium.

I confess that as I stood before the original Removal Act at the National Archives, it was hard for me to reconcile the events it set in motion with the motorcycle’s very American celebration of freedom. The curators of Americans hope, however, that the new exhibition will encourage visitors to be part of a new conversation among Natives and non-Natives about the place Indians continue to hold in our understanding of America. It’s an important conversation, and I’m committed to being part of it.