NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Anna May Wong’s Long Journey From Hollywood to the Smithsonian

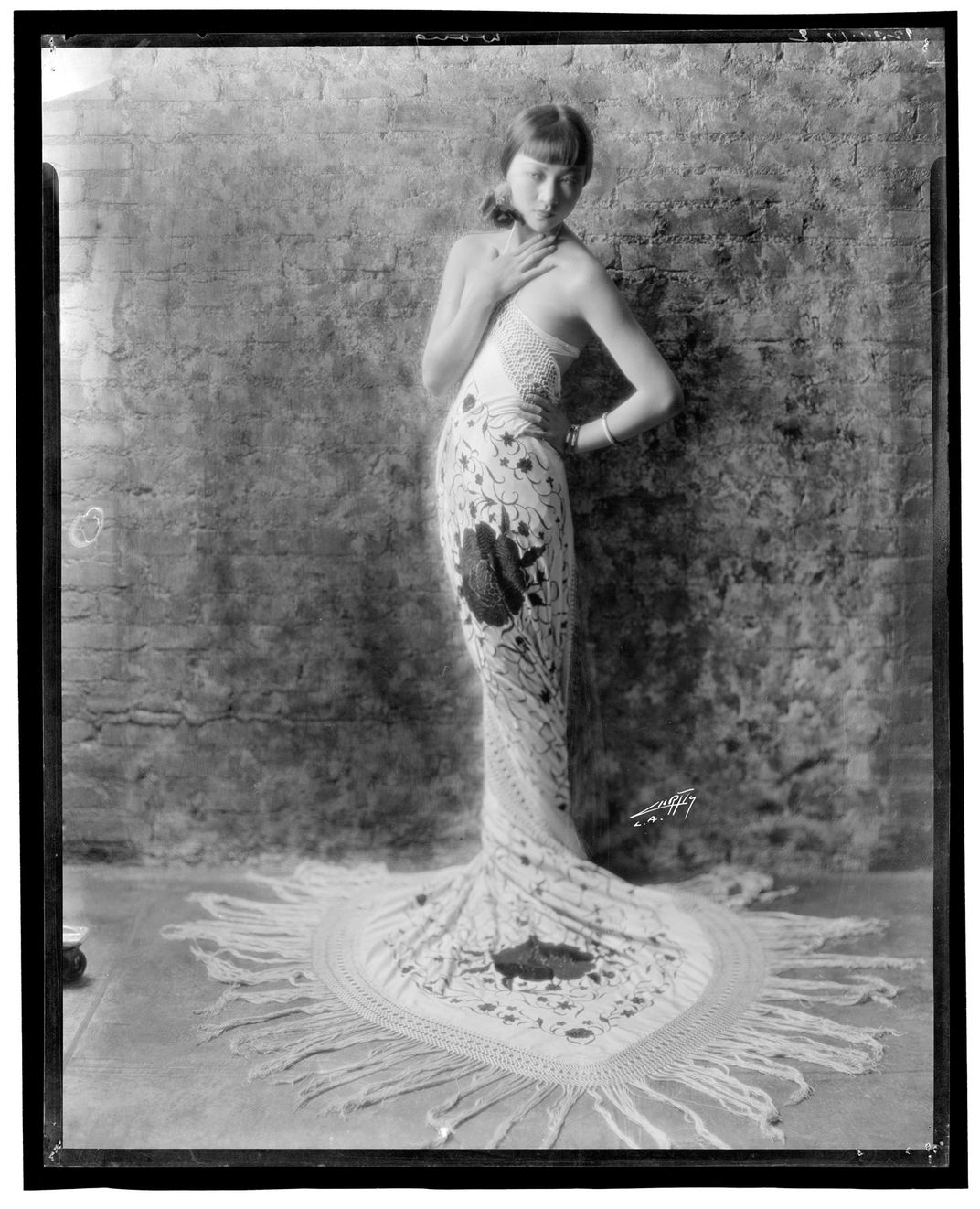

Anna May Wong built a remarkable career, she became a legendary style icon.

:focal(711x903:712x904)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/74/c474eee5-a091-43d6-aa9c-369afeb71b53/npg_99_45_wong_r.jpg)

From new biographies to Hollywood biopics to the reverse side of a quarter, it seems like Anna May Wong is everywhere these days—and that’s a good thing.

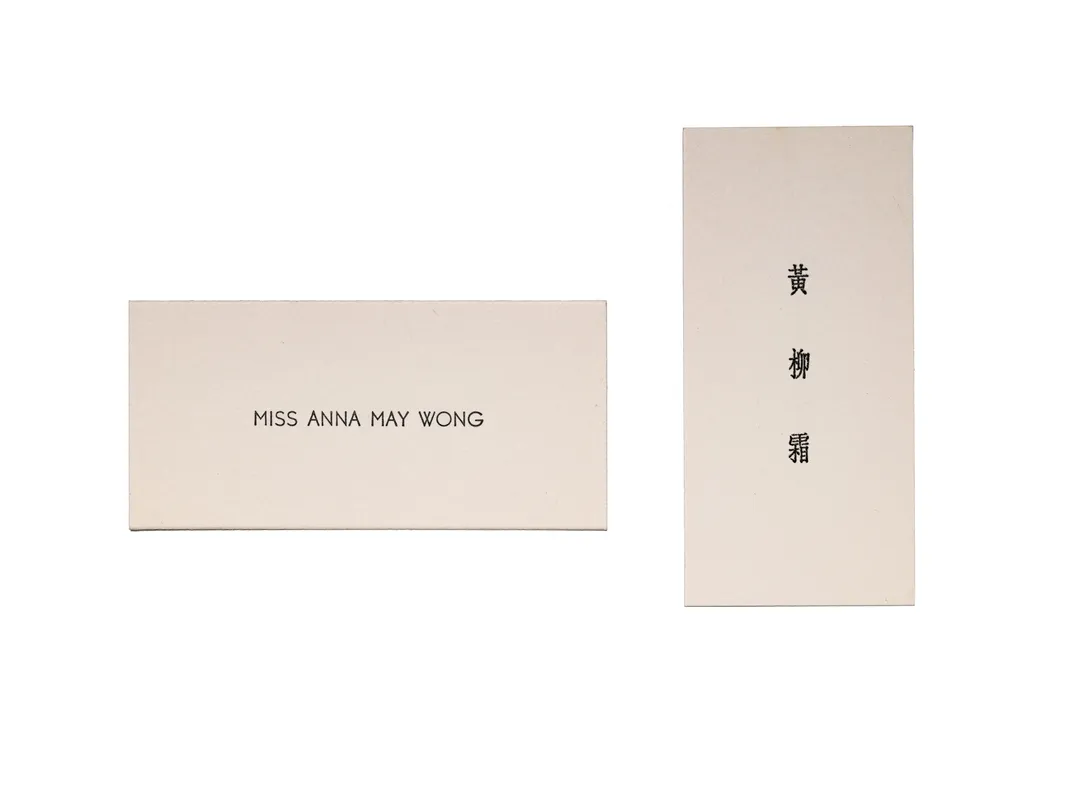

Wong, a groundbreaking Chinese American actress, is finally getting the recognition that she was denied by the racist American film industry of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Wong built a remarkable career. She became a legendary style icon and paved the way for other Asian American actors to follow—all the while battling prejudice and stereotyping still so profound that it was not until 2023 that a woman of Asian ancestry would win an Academy Award for Best Actress. Thanks to the generosity of Wong's niece, our museum recently collected objects that will help us illuminate her pathbreaking life and career.Anna May Wong was born on January 3, 1905, in Los Angeles, to second-generation Chinese Americans—a family that had moved to the United States from Taishan in the Guangdong province of China during the 1850s. She was given the name Wong Liu Tsong 黃柳霜—meaning “yellow willow frost”—and grew up in a family of seven children in and around Los Angeles’s Chinatown. Wong’s father, Wong Sam-sing, was the owner of Sam Kee Laundry and a respected member of the local community. In an era marked by anti-Chinese prejudice and anti-immigrant legislation like the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese Americans struggled to find work. Laundry work was one of the few employment opportunities for families like the Wongs; an estimated one in four men of Chinese ancestry in the United States worked in a laundry around the year 1900.

Growing up in the diverse neighborhood around Los Angeles’s Chinatown, Wong was nevertheless taunted and bullied for her Chinese ancestry. She yearned for something more than the grueling labor and limited social world of her upbringing; she dreamed of fame, fortune, and acceptance for who she was. Despite the prejudice she experienced there, Wong's hometown would provide unique avenues of opportunity for these ambitions.By the late 1910s, the American film industry had begun moving from the New York area to the West Coast, seeking the year-round warmth, sunshine—and looser labor laws—of California.

Wong earned her first starring role at the age of 17, portraying the doomed Chinese lover of an American man in the early Technicolor film The Toll of the Sea (1922), a loose adaptation of the Madame Butterfly story. She won accolades for her natural acting talent and stage presence, and she began landing roles in more prominent films, including The Thief of Bagdad (1924) starring action/adventure idol Douglas Fairbanks. With her slim physique, modish bobbed hair, cutting-edge style, and natural confidence in front of the camera, Wong also became an in-demand fashion model. She crafted an image as a modern Chinese American woman, proud of all facets of her identity.

When it came to films, however, Wong increasingly found her opportunities limited to a range of roles that embodied harmful stereotypes about Asian and Asian American women, including the scheming “Dragon Lady,” the “Butterfly”-type doomed lover of a white man, or the alluring and sensual concubine. Frustrated by her limited opportunities in Hollywood despite her rising fame, Wong decamped for Europe in 1928. There, she starred in several of her most acclaimed films, including Pavement Butterfly (1928) and Piccadilly (1929).

When Wong returned to the United States in 1930, her star had never been brighter. Lauded by European critics, she took a dramatic role on Broadway, continued to land roles in major movies, and signed a new contract with Paramount Studios. In Daughter of the Dragon (1931) and Shanghai Express (1932), she worked with some of the top talent in the industry, earned rave reviews, and helped make these films major successes at the box office—but at the cost of playing stereotypical characters once again. Wong believed that she deserved more and longed to prove herself in a major romantic leading role, as she’d performed in European films. However, Hollywood studios’ production code barred on-screen portrayals of interracial love, severely limiting her chances for the big break she sought. There were only a few Asian American male stars in Hollywood, and films headlining Asian American couples were even rarer.

One of Wong’s greatest opportunities—and greatest heartbreaks—was the MGM production of Pearl S. Buck’s bestselling and Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Good Earth, which told the story of noble and hardworking Chinese peasants striving against great odds. When MGM optioned the story for a major motion picture, Wong lobbied hard to play the sympathetic, long-suffering female lead O-Lan in the film. Sadly, once producers cast white actor Paul Muni in the male lead, they instead hired white Louise Rainer to play O-Lan in yellowface, in accordance with the industry’s rules about interracial romance. They suggested that Wong could try out for the supporting role of Lotus, yet another prostitute. Rainer would go on to win the 1938 Academy Award for Best Actress. The entire episode was a profound career disappointment for Wong that soured her on Hollywood once again.

In the late 1930s, Wong embarked on a highly publicized tour of China. She focused on smaller-budget, lower profile B movies where she could exercise more creative control and play parts she desired. At the same time, she began to advocate for China in its resistance against Japanese aggression. She even auctioned off her movie costumes and sent the proceeds to Chinese aid organizations. Though she was no longer considered for major roles, throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Wong continued to work in B movies, radio, and television. She struggled with alcoholism, depression, and financial woes in her later life but never gave up on her dream to better represent the fullness of Chinese American life in American entertainment. Wong became the first Asian American actor to headline a television series with the Dumont network's anthology series The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong in 1951. She was attempting a film career comeback with a role in the major musical Flower Drum Song when she died of a heart attack in 1961.

For decades, Anna May Wong’s groundbreaking career was largely forgotten, but in recent years scholarly and popular interest have helped revive her memory. In 2022, the American Women Quarters program released a quarter with an illustration of Wong on the tails side, making her the first Asian woman to appear on U.S. currency. Characters inspired by Wong and her life story have appeared in the Netflix series Hollywood and the 2022 film Babylon, and Gemma Chan is slated to star in a biopic about Wong’s life, currently in production.

These objects were displayed for the past year on the museum floor, alongside a quote that speaks to Anna May Wong’s disappointment in the entertainment industry that typecast and restricted her: “When I die, my epitaph should be: I died a thousand deaths. That was the story of my film career. . . . They didn’t know what to do with me at the end, so they killed me off.”

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on May 9, 2024. Read the original version here.