NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Does Thanksgiving Have Room for Both Thankfulness and Mourning?

Through acts of protest and education, Wampanoag and other Native Americans have long urged other Americans to reconsider the Thanksgiving myth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/f8/cef8ceae-d010-4d73-b984-9c8f134faa5f/banner.png)

Is there room in Americans’ Thanksgiving celebrations for both thankfulness and mourning?

That challenging question arose as my colleagues and I took a new look at encounters in the 1600s between English Pilgrims and the Wampanoag people in eastern Massachusetts. A showcase exhibition, titled Upending 1620: Where Do We Begin?, now shares our findings—and our questions—near the National Mall entrance to our museum.

The exhibition re-examines a familiar Pilgrim story, in which a small group of pious English, fleeing the authority of the established Church of England, crossed the Atlantic on the ship Mayflower to worship as they saw fit. They suffered a devastating New England winter, but those who survived providentially found help from the Wampanoag, who taught them to grow corn and shared other vital skills.

In the fall of 1621, the small English community gathered to celebrate the harvest and give thanks to their Maker for their survival. Together with local Wampanoag, they held a harvest feast. It was several centuries later that other European Americans would dub that gathering the “First Thanksgiving,” marking it as the apparent forerunner of the national holiday most Americans still observe today.

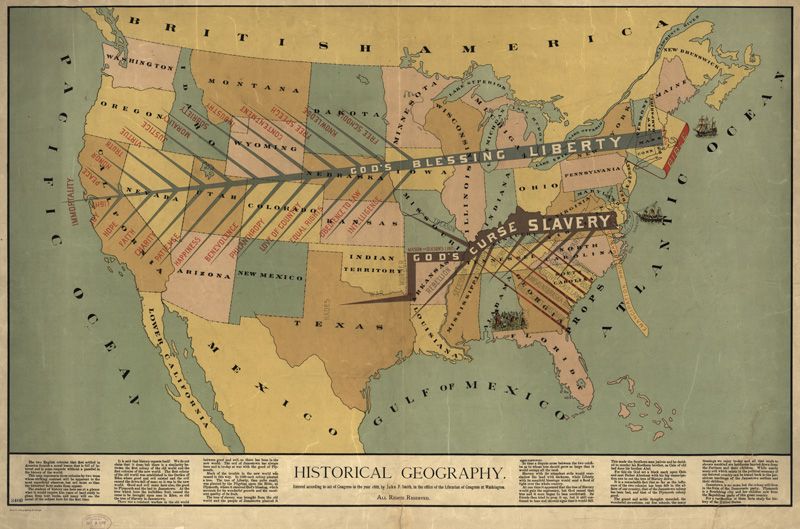

In fact, many later Americans elaborated the Pilgrim story as if it represented U.S. history as a whole. Not always concerned with accuracy, the storytellers pressed these events from the 1600s into an origin myth for the entire nation.

They got things wrong; the Mayflower passengers rarely called themselves “Pilgrims,” and their contemporary records make no mention of landing on a great “rock” in Plymouth Harbor. Far more consequentially, they disregarded the Wampanoag perspective and excluded the devastating events that followed in the years after 1621.

Freezing history at a moment of harmony and reciprocity, the Pilgrim story has carried great appeal. Yet the shared joint feast of gratitude was never repeated, and within a few decades the influx of English immigrants created intense pressure on Wampanoag lands. English incursions resulted in fierce conflict and left severely weakened Wampanoag societies. The victorious English even sent some captives of war into enslavement in the British West Indies. Only through highly selective memory, then, could later storytellers use Pilgrims and Wampanoag to rationalize their own generations’ continued acts of expansion into indigenous lands in the American West.

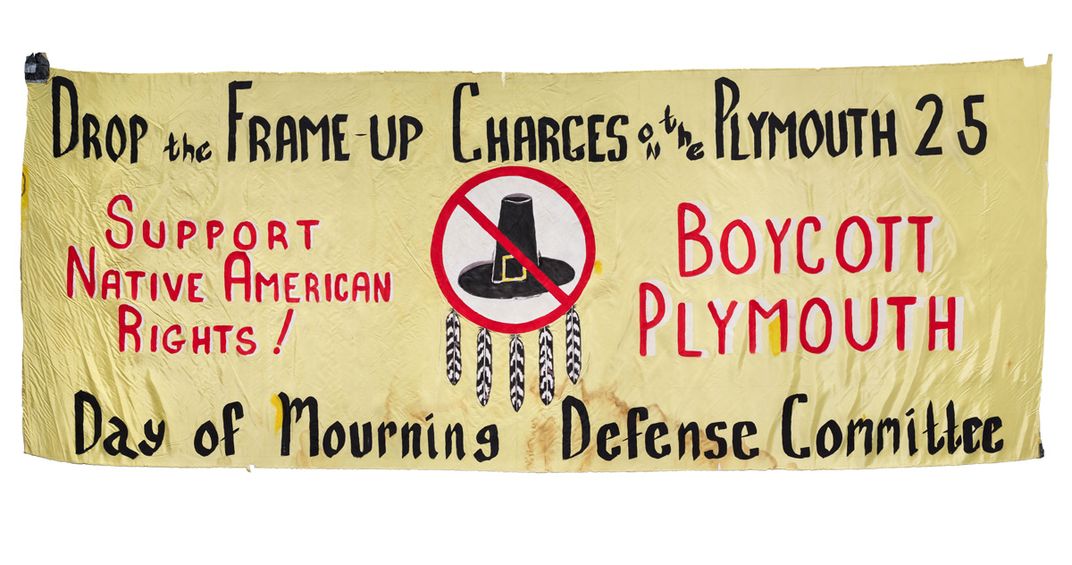

Through acts of protest and education, Wampanoag and other Native Americans have long urged other Americans to take these realities on board. Over the past half-century, some have observed the fourth Thursday in November as “A Day of Mourning” for their historic losses. They gather to bring attention to repeated wrongs against their ancestors, to dispel the myth of Native Americans’ “disappearance,” and to celebrate their own persistence as a people and a culture across the centuries.

By doing so, they challenge other Americans to learn from the past and to acknowledge some key truths: Even pious bands of believers might still act as colonizers. Great disparities of power do not yield harmony. And the essence of colonialism—the belief that other lands and even other peoples exist for the purposes of the colonizers—continues to carry seeds of violence in our world.

And so we need such knowledge to more fully understand the nation we inherit and to chart a tolerable future society for our children.

As I see it, recognizing the tradition of mourning more broadly as part of our national November ritual can give renewed meaning to Thanksgiving. It can help all Americans move forward with clearer eyes and renewed gratitude.

Once again, the Wampanoag are offering essential knowledge to the newcomers.

Middle and high school students can explore many of the objects and histories that inform Upending 1620 in the exhibition's companion Learning Lab collection. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian has online resources that explore the history and meaning of Thanksgiving.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on November 22, 2021. Read the original version here.