NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The Day I Decided Not to Collect: A Curator’s View of Ground Zero

It was not my place to ask the workers for anything, but to thank them for their tireless service.

:focal(275x182:276x183)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Sept_11_6.jpg)

About a month after the terrorist attacks on 9/11, I received a phone call from a colleague asking if I wanted to take a trip up to New York City to collect objects from Ground Zero for the museum. Although now a curator with the sports collection, at the time I was the curator of the fire and rescue collections and he thought I would like to collect from the fire and rescue personnel on site. I hesitated for a minute, knowing this would not be an easy scene to witness, but accepted his invitation.

It was a beautiful fall day with blue skies and cool, crisp air, much like September 11 had been. We drove up to the site, passing mini blinds tangled in the few trees that were left, and were struck by the sheer volume of paper. Sheets and sheets of financial documents and correspondence from all of the various offices that had once filled the World Trade Center littered the site. The damage to many of the surrounding buildings was severe and most were in need of major repair or demolition.

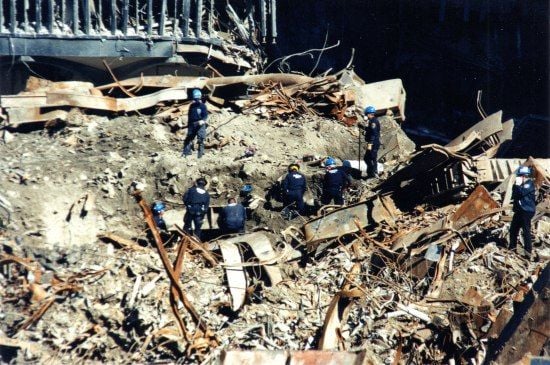

As we stepped out of the cab and onto Ground Zero, I saw complete and utter devastation. The smell of concrete and decay was overwhelming, as was the size of the actual hole left by the collapse of the World Trade Center towers. The debris that filled part of the hole—or the "pile," as it was called by rescue personnel—was still very high and was active with all types of workers present. Welders, carpenters, engineers, riggers, sheet metal workers, and many others from the building trades were shoring up the surrounding buildings and stabilizing the debris pile. Police and rescue personnel along with rescue dogs were sifting through the debris looking for any kind of recoverable remains. Firefighters were putting out active fires within the pile, which had been flaring up since the buildings came down.

Seeing the site on television was horrific but seeing it in person was worse. I had been an emergency medical technician (EMT) with the Kensington Volunteer Fire Department in Maryland for five years and had been to many accident scenes and fire grounds, but this was completely different. The sense of urgency was almost palpable as these workers, many from other states and from different trades, worked together to make the site accessible to the rescue personnel. Many were still hoping to find survivors, but at this point knew it was more of a recovery mission. For all of the work that was going on, the pile was eerily quiet.

Hard hats protected us from falling debris and surgical masks helped keep the dust at bay. The dust was unbelievably fine and got through the masks easily, making them essentially useless. Everything was covered in a layer of that fine gray dust that made it look like we were in a black-and-white movie, except for the different colored hard hats and uniforms the workers and rescue personnel wore.

Visiting the many aid stations where the workers could go to get something to eat or just decompress was very humbling. Experience told me their emotions were too raw to approach them about donating objects to the museum. Most were exhausted from working so hard and for so long, digging through this huge pile of debris, finding nothing or, even worse, a fallen brother. As a curator, I know the importance of collecting, and I rarely shy away from an opportunity to bring a storied object into the museum's collections. But on that day, it was not my place to ask these guys for anything, but to thank them for their tireless service.

Instead of collecting objects, I used my camera to record the events of that day and donated the images to the museum's Photographic History Collection—a few of which you see here. The museum did eventually collect from many of the firefighters, police officers, rescue workers, and various trades represented in the clean-up from Ground Zero. Objects were collected from the two other sites created that day—the Pentagon, in which a hijacked plane crashed into the building, killing everyone aboard the plane and many on the ground, and Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where the heroic crew and passengers rushed the cockpit to bring the plane down before it could make it to another possible target, thought to be the Capitol in Washington, D.C. Congress designated the museum as the official repository of the story of 9/11, and the museum continues to collect artifacts that reflect what happened that day and the aftermath. These collections are among the most extensive in the country and we are honored to be able to preserve these objects for future generations so that we may never forget.

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of the attacks, the museum is hosting a series of programs exploring their lasting impact. The museum is also launching a story collecting project—share your 9/11 story with the Smithsonian here.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on September 8, 2017. Read the original version here.