NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

How Chef Lena Richard Became a Culinary Icon and Activist

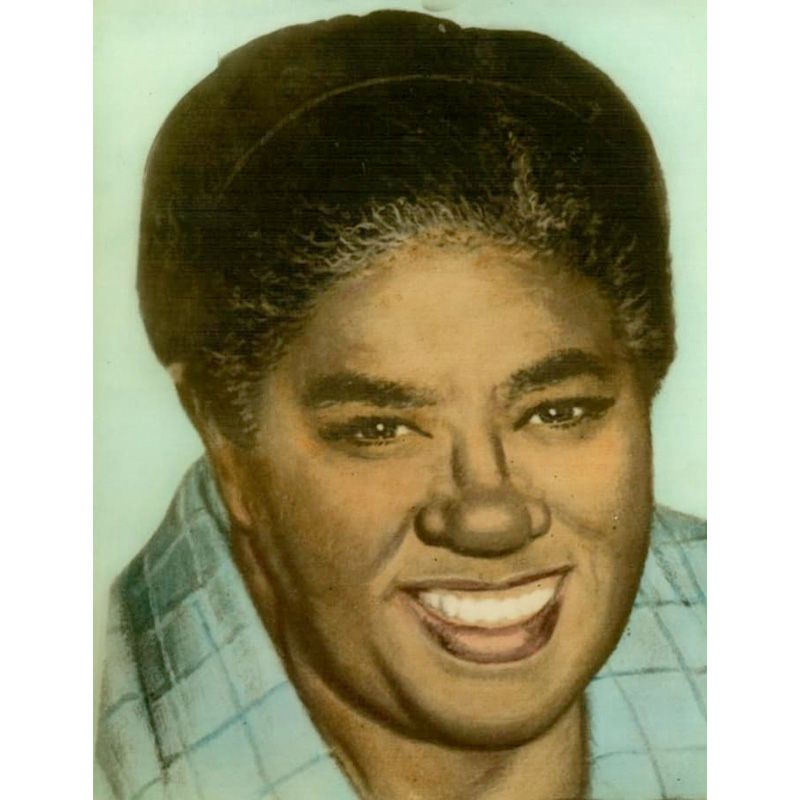

Lena Richard was an African American chef who built a culinary empire in New Orleans during the Jim Crow era.

:focal(404x492:405x493)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Lena_Richard_Newcomb_Archives_Vorhoff_Library_Sq.jpg)

Lena Richard was an African American chef who built a culinary empire in New Orleans during the Jim Crow era. She reshaped public understanding of New Orleans’ cuisine by showcasing and celebrating the Black roots of Creole cooking in a time when pervasive racial stereotypes surrounded the food industry. Her story, however, has never been given its proper due.

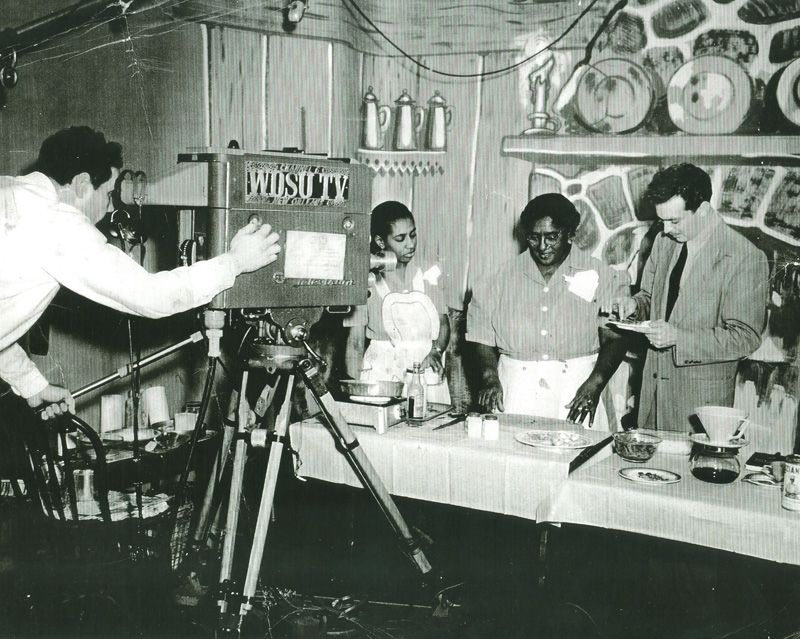

Throughout her career, Richard owned and operated catering businesses, eateries, a fine-dining restaurant, a cooking school, and an international frozen food business in the racially segregated South. Her reputation as one of New Orleans’ finest chefs launched her into early food TV in a time of few African American stars.

Spreading the Knowledge

Richard understood culinary training as a tool that young African American cooks could leverage to build better lives for themselves. In 1937 she opened a cooking school specifically for Black students. She envisioned the school as a place “to teach men and women the art of food preparation and serving in order that they would become capable of preparing and serving food for any occasion and also that they might be in a position to demand higher wages.” In this way, Richard taught her students a recipe for resilience based on professional development and self-advocacy. These tools helped her students navigate the race- and gender-based barriers embedded in the food service industry.

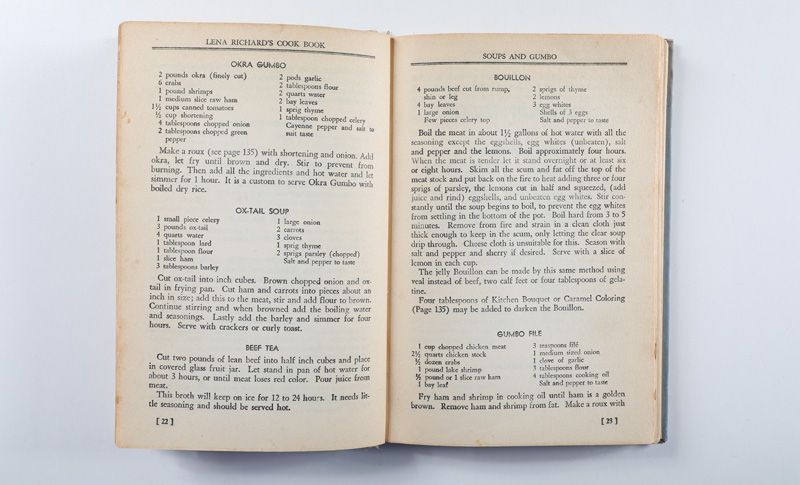

The same year, she began writing a cookbook with her daughter, Marie. In between culinary classes and catering events, they collected and transcribed Richard’s vast knowledge into around 300 recipes. These included Creole classics like gumbo and court bouillon as well as dishes popular throughout the United States such as Brunswick stew and Baked Alaska. Richard created the recipes herself or adapted community favorites to fit her cooking style. When Richard published Lena Richard’s Cook Book in 1939, she became the first African American author of a published cookbook featuring New Orleans Creole cuisine.

Rewriting the Narrative

Before Richard’s cookbook, white cookbook authors narrated the history of the city’s Creole cuisine from their own perspectives, often downplaying or ignoring the role of Black cooks, chefs, and culinary professionals. In 200 Years of New Orleans Cooking (1931), for instance, author Natalie V. Scott reduces African American cooks’ culinary skills to a “sixth culinary sense,” writing that it was with some “mastery of mental telepathy” that Black cooks became “miraculously aware of this way of dealing with a vegetable, that way of concocting a soup.”

Cookbooks that labeled African Americans’ cooking skills as “innate” and “magical” contributed to stereotypes of Black women as “alien” and “other” as well as submissive and non-threatening to white Americans. This is most recognizable in the caricature of Aunt Jemima, the stereotypical Mammy figure used to promote branded pancake mix through most of the twentieth century. Journalist Toni Tipton-Martin writes that this stereotype “assumes that Black chefs, cooks, and cookbook authors—by virtue of their race and gender—are simply born with good kitchen instincts.” Such a stereotype of African American chefs “diminishes [the] knowledge, skills and abilities involved in their work, and portrays them as passive and ignorant laborers incapable of creative culinary artistry.”

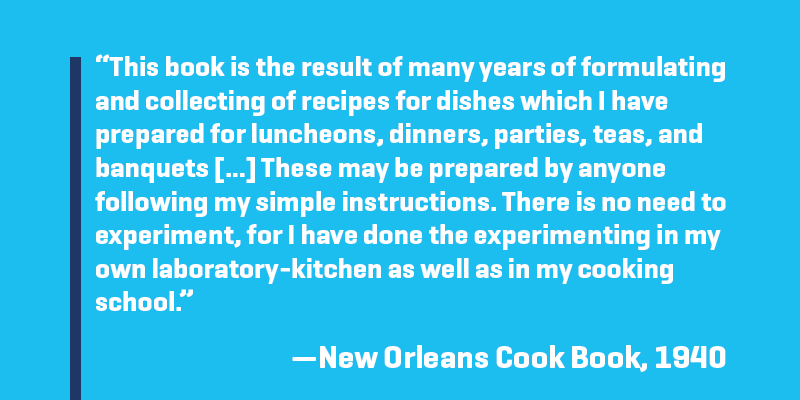

Richard’s cookbook broke down these harmful stereotypes by emphasizing the labor, time, and training that went into her work. She not only tested and perfected the recipes after years of culinary experience, but also taught them to students in her cooking classes to ensure their quality and replicability. By creating her own cookbook and copyrighting it, Richard claimed those recipes—many of which had been taken without permission and published by white cookbook authors—for herself and her community.

Reaching the Masses

Upon release, Lena Richard’s Cook Book quickly captured the attention of local readers, many of whom shared Richard's work with friends and family outside of New Orleans. Within a week, Richard received almost 200 letters of inquiry and orders from people in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, among other U.S. cities.

Hearing how hungry Americans were for a well-written Creole cookbook, Richard and her daughter headed to the Northeast to promote it so that “up North folks know how good down South folks eat,” as noted food writer Clementine Paddleford in 1939. Unsure of ingredients she’d be able to find in Northern markets, Richard went to New York “with her suitcase bulging with ten pounds of dried shrimp, pure cane syrup, Louisiana shelled pecans and old-fashioned brown sugar.”

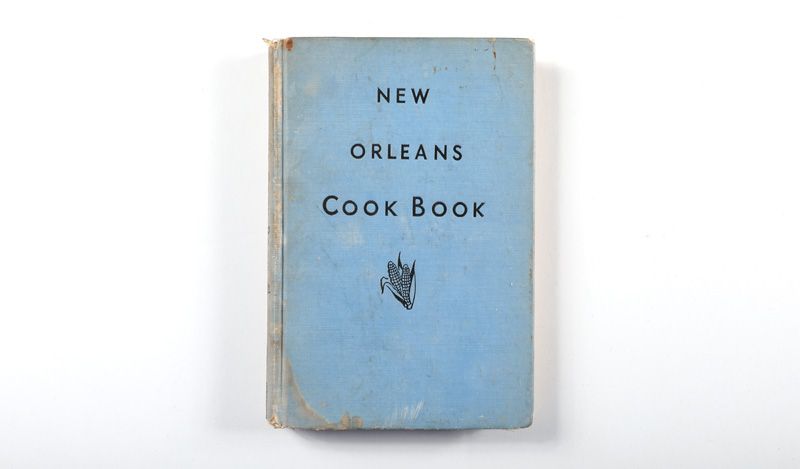

While in New York, Richard connected with Houghton Mifflin Company representatives who expressed interest in publishing her cookbook nationally. Soon after, the company printed Richard’s work under a new title, New Orleans Cook Book (1940). This edition featured a new preface where Richard establishes her experience as a professional chef and her scientific approach:

Richard’s work was anything but “magical” and “innate.” Rather, it was the product of years of professional training and work by a chef who, with the support of her family and community, found ways to rewrite harmful historical narratives. In doing so, she created a cookbook that acknowledged and celebrated the ingenuity, strength, and perseverance of African Americans.

Interested in trying a recipe from Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book? Check out her recipes for gumbo and share your experiences with us by using the #SmithsonianFood.

The American Food History Project is made possible by Warren and Barbara Winiarski│Winiarski Family Foundation and supporters of the Winemakers’ Dinner and Smithsonian Food History Gala.

Leadership support for American Enterprise in the Mars Hall of American Business was provided by Mars, Incorporated; the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; and SC Johnson.

Learn more about Lena Richard on the Sidedoor podcast.