AMERICAN WOMEN'S HISTORY INITIATIVE

Using Data Science to Uncover the Work of Women in Science

Scientists’ personal papers often offer key insights into a scientist’s goals and character. Without them, digital curator Dr. Elizabeth Harmon must act as a detective.

:focal(395x302:396x303)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/86/1d/861daaf0-9cf7-4aa1-8fe5-e1d4eba692c9/service-pnp-hec-42800-42882v.jpg)

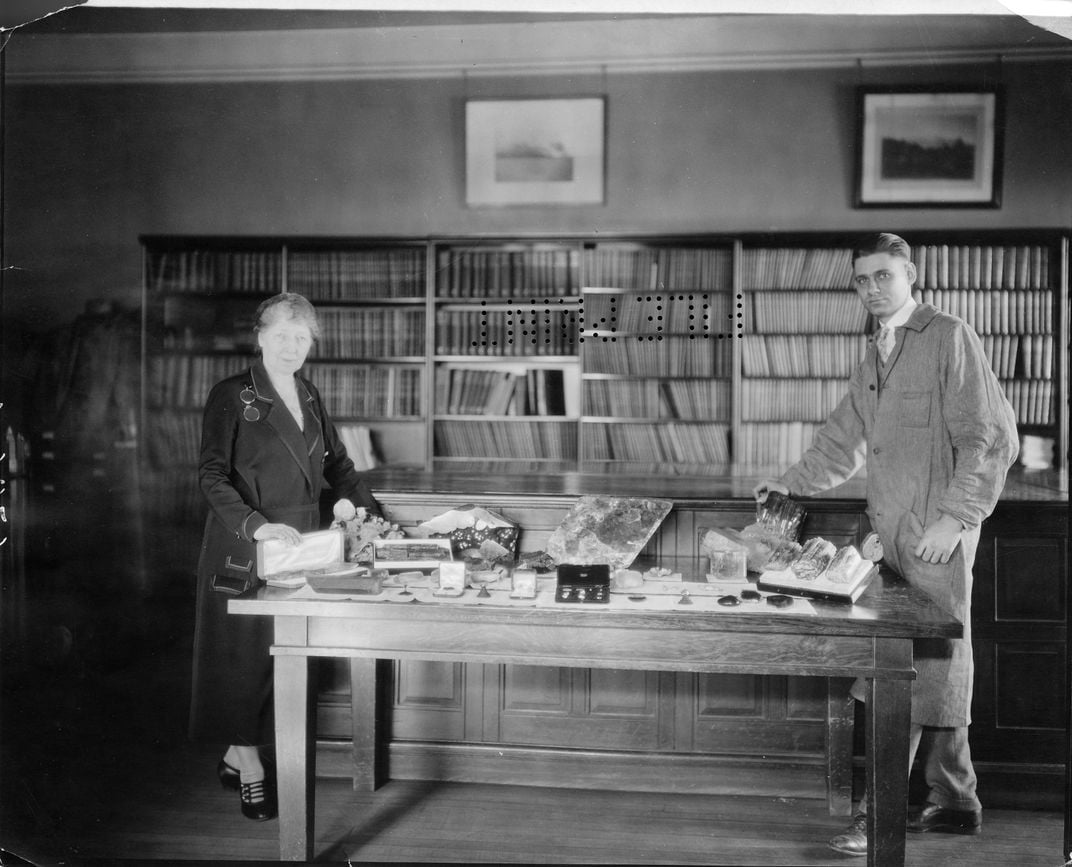

Margaret W. Moodey was one of the first women to work at the Smithsonian in science. Beginning around 1900, Moodey worked as a scientific aide in the Smithsonian's Department of Geology. Her work included identifying, classifying, and cataloging samples, including gems and fossils. By 1924, an annual report notes that she "had the entire responsibility and care of the collection of cut gems." Moodey was an important resource for anyone seeking answers about the collection. In total, she worked for more than 40 years at the Smithsonian.

Moodey may have been an inspirational example to other women interested in careers in science. Photos of her using a microscope were published in newspapers and magazines across the nation.

Dr. Elizabeth Harmon, a digital curator at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, uses Moodey's scientific publications to explore her legacy. Moodey is also mentioned in annual reports, departmental records, and in her boss's papers. The papers of her male colleagues are often preserved in the Smithsonian's archives. Moodey's were not.

"We know from interviews and writings that some women didn't think that their papers were notable enough to save and share with archives," Harmon said. "Additionally, historians have argued for decades now that women's records are harder to find in historical collections because museums, libraries, and archives have been slower to collect records about women. And when they do, information about women is often scattered across various collections or hidden behind the work and records of male colleagues and relations."

Personal papers often offer key insights into a scientist's goals and character. Without them, Harmon must act as a detective. She searches through extensive collections, including departmental records, phone books, payroll records, newsletters, newspapers, and census records, to learn about the women who made science possible. Sometimes her team finds more women working than anyone had realized.

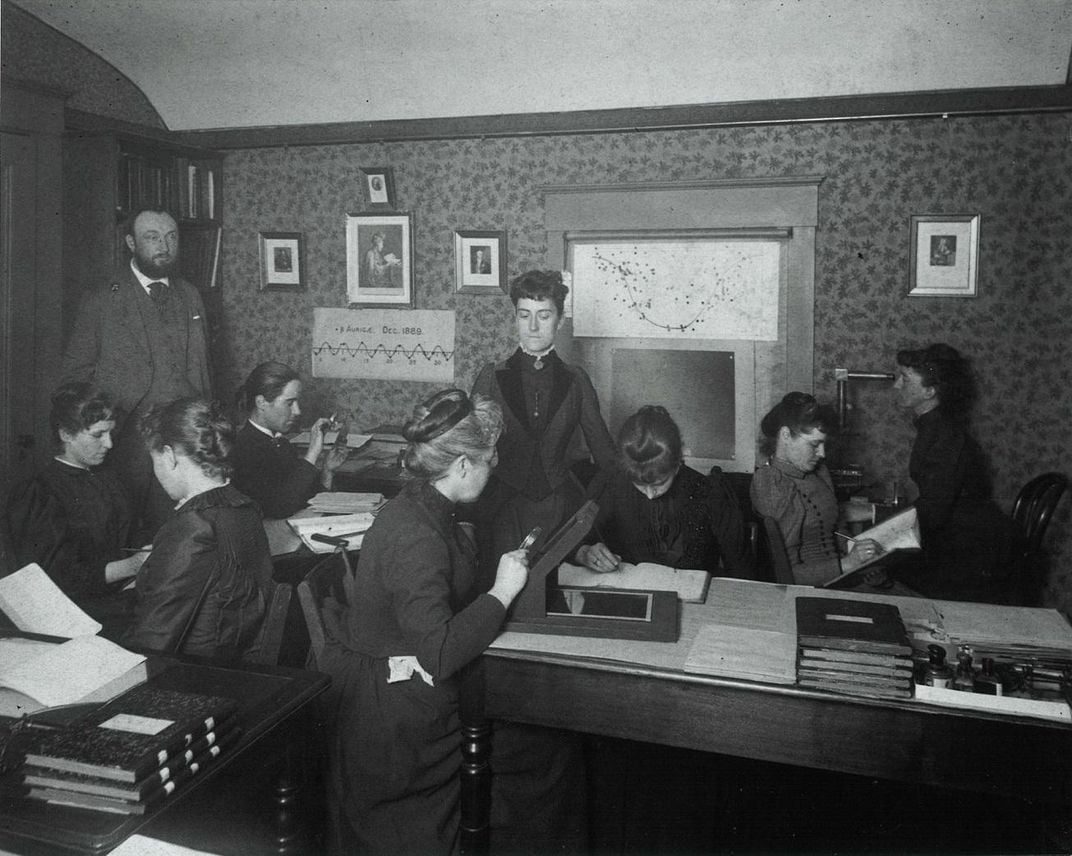

"This summer, Nell MacCarty, an American Women's History Initiative intern, was poring through annual reports from the Smithsonian's Astrophysical Observatory," Harmon recalled. "She was finding a lot of references to women collecting specimens while they were at field stations. She found women named as assistant directors, and their names hadn't appeared on staff lists. We have to be able to skim hundreds of thousands of pages to tell these stories comprehensively."

To speed this important work, Harmon partners with Dr. Rebecca Dikow at the Smithsonian Institution Data Science Lab, part of the Office of the Chief Information Officer. Dikow is developing tools that will help review records and flag women for further research. Dikow uses names of known women as a starting point. Still, there are plenty of challenges for Dikow.

"We have lots of digitized, scanned text," Dikow said. "But a lot of our historical documents are typewritten in ways that are challenging for computers to identify each letter accurately. Our post-doctoral fellow Dr. William Mattingly is working to understand the kinds of challenges our documents present for automatic transcription."

Dikow and her coworkers at the Data Science Lab are also careful to build tools that do not assume gender based on the names mentioned in annual reports. "Customization is necessary at every step," she said. "We really want to focus on accuracy to make sure that we are not just identifying men in these documents."

Because women's accomplishments are not always recorded clearly, Harmon and her team must review each name identified. Dikow shared one example that helps explain why.

In 2019, Smithsonian Data Science Lab fellow Tiana Curry found that dozens of botanical samples collected by a woman were misattributed. The samples were collected by natural historian, botanist, and artist Mary Vaux Walcott, yet were listed under her husband's name in the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History database. Walcott's husband was paleontologist and Smithsonian Secretary Charles D. Walcott.

Curry spotted that the samples were collected after 1927, the year of Charles's death. The Data Science Lab team was able to spot cursive lettering for "Mrs. C. D. Walcott" on scanned handwritten collection cards. When text from cards is added to databases, titles are often removed. The collector's name is often more important than the title. Yet, in this case, removing the title erased a woman's contributions to science. Curry uncovered several other examples where Mary Vaux Walcott's collections were misattributed.

Dikow and Harmon shared another reason why we know less about women in the sciences: their work has often been seen as less valuable. Since the 1960s and 1970s, scholars have begun to expand studies to include those who make research possible. Harmon said, "Before, it was more common only to collect the papers of someone who was a curator or a primary investigator. Over time, people have been more and more curious about those working in support, administrative, and tech positions. A major trend in the history of science is to be more inclusive. We want to increase who is included in this category of women in science."

One example is Sophie Lutterlough, who worked as a research assistant to insect curator Ralph Crabill at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. One annual report mentions that Lutterlough and Crabill processed 300,000 specimens that year, but it's hard to find more details about Lutterlough's scientific work in Smithsonian collections. Dikow said, "She's such a good example of someone who didn't get scientific credit for her work but enabled so much scientific work to happen."

There are still many women whose work at the Smithsonian, and in science at large, has yet to be uncovered. Harmon is working on an online exhibition to debut next year that will help share some of the most exciting stories from her research. She said that her work is stronger thanks to Dikow. "Working collaboratively, being inspired by the Data Science Lab is so important to me," she said. I can imagine these stories that are scattered in our records coming together to paint a bigger picture of the contributions of these women in science."