When Thanksgiving Meant a Fancy Meal Out on the Town

From the Gilded Age to the Great Depression, the menu had a lot more than turkey and stuffing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131125103126Thanskgiving-1916-Greyhound-Inn-470.jpg)

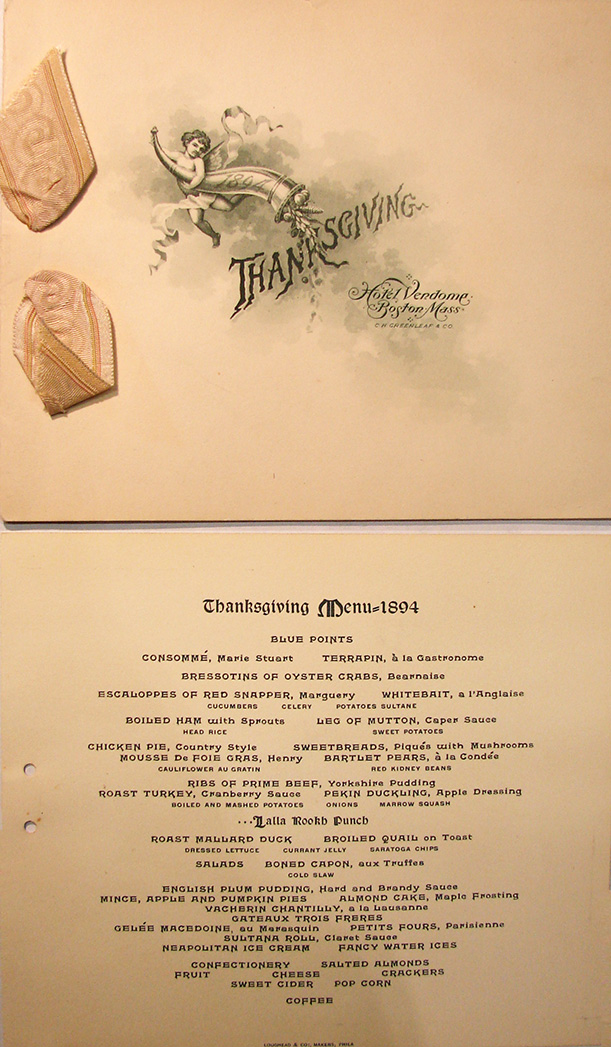

A few years back, when she was the director and librarian of the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Peggy Baker came across a fascinating document at a rare book and ephemera sale in Hartford, Connecticut. It was a four-course menu for a luxurious dinner at the Hotel Vendome in Boston for November 29, 1894 – Thanksgiving.

Appetizers consisted of Blue Point oysters or oyster crabs in béarnaise sauce. The soup is consumee Marie Stuart, with carrots and turnips; or, a real delicacy, terrapin a la gastronome (that’s turtle soup to you).

The choice of entrees included mousee de foie graise with cauliflower au gratin, prime ribs with Yorkshire pudding, Peking Duck with onions and squash and…a nod to the traditionalists…roasted turkey with cranberry sauce and mashed potatoes.

Then, salad—at the end of the meal, as they do in Europe—followed by a plethora of desserts: Petit fours, plum pudding with maple brandy sauce, Neapolitan ice cream; mince, apple and pumpkin pie, and almond cake with maple frosting. To round out the meal, coffee or sweet cider with assorted cheeses and nuts.

Baker’s discovery of this belt-busting tour de force sent her on a mission to shed light back on a long forgotten chapter of the history of this holiday; a time when wealthy Americans celebrated their Thanksgivings not in the confines of the home with family, but at fancy hotels and restaurants, with extravagant, haute cuisine dinners and entertainments.

“I was thoroughly entranced, having no idea any such thing existed,” recalls Baker. She began collecting similar bills of fare from other establishments, in other cities.

“It was like an anthropological expedition to a different culture,” recalls Baker, “I wasn’t aware people dined out as a regular annual event for Thanksgiving. It was just so foreign to me.”

The menu from the Hotel Vendome that sent Baker on her mission.

Baker amassed more than 40 of these menus, which she displayed at the museum in 1998, in an exhibit called “Thanksgiving a la Carte.” Baker retired in 2010, but the pieces from the exhibit can still be viewed on the Pilgrim Hall Museum website. (PDF)

The reason a Thanksgiving Day spent anywhere but home seems so jarring today, is due in large part to the power of a painting: Norman Rockwell’s 1943 “Freedom from Want”—part of the famous “Four Freedoms” series that Rockwell painted as part of the effort to sell War Bonds. Published on the cover of the March 6, 1943 edition of the Saturday Evening Post, the painting depicts a kindly-looking, white-haired patriarch and matriarch standing at the head of the table, as hungry family members—their smiling faces only partially visible—eagerly anticipate the mouth-watering turkey dinner that’s about to be served.

But Rockwell’s idealized Thanksgiving celebration is not the way it’s always been; it could even be argued that the idea of a tightly-knit family celebration at home would have been unfamiliar to even the Pilgrims.

“The meal we harken back to in 1621, is a totally anomalous situation to the way we think about it today,” says Kathleen Wahl, a culinarian and 17th-century food expert at Plimouth Plantation, the living history museum of the Pilgrim period in Plymouth, Massachusetts. “You have about 50 English people whose families were torn apart, by death or distance. It’s like a very modern, make-do family. Family is your neighbors, it’s whoever happens to be in the situation with you.”

Those survivors of the first winter in the New World celebrated the harvest with the Wampanoag sachem Massasoit and about 90 of his men. While there were no restaurants or catering halls in 1621, this was about as close as you could come without a waiter taking Squanto and Miles Standish’s drink orders. “The original Thanksgiving dinners was an `out of home’ experience,” Wahl argues. “I think going out is more in the tradition of the 1621 event.”

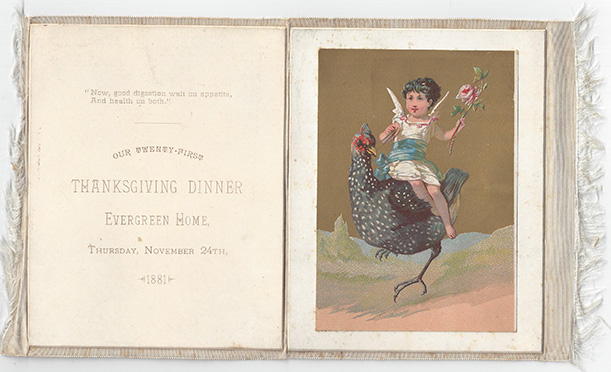

The 1881 menu from the Evergreen Home.

According to James W. Baker, author of the 2009 book Thanksgiving: the Biography of an American Holiday (and husband to Peggy), part of the celebration has always involved events outside the home. Thanksgiving Day Balls were popular in New England in the early 19th century—although they followed a day that included church services and a meal at home. “The dinner was just one small element along with these other things,” said Baker, “but over the years it’s swallowed up the other things.” The primacy of the meal continues in more recent times. Things like the Thanksgiving Day parade, the high school football game, the local foot race, have all become common holiday events in various parts of the country, but they are usually done in the morning, allowing participants to race home for the family dinner.

It seems to have been during the Gilded Age when the Thanksgiving banquet at the luxury hotel or restaurant first became popular. This coincided with a general movement into fashionable new restaurants by the upper class. “Before then, you stayed home because you didn’t want the riffraff to see what you were doing,” says Evangeline Holland, a social historian who writes about the late Victorian and Edwardian periods on her website edwardianpromenade.com “But with the rise of the nouveau riche, people in England started dining out at restaurants and Americans followed suite.”

What better day to flaunt what you had than on Thanksgiving? “With the Gilded Age, everything is over the top,” says Stephen O’Neill, associate director and curator of collections at Pilgrim Hall Museum. “Thanksgiving is very much a celebration of abundance, so I think they sort of used that as an excuse to promote these extravagantly large dinners.”

The affairs were held at such famous, luxury hotels and restaurants as the Vendome, Delmonico’s and the Waldorf Astoria in New York. Even luxury cruise ships got into the act, offering elaborate Thanksgiving Day dinners to their seaborne passengers. The upper crust in smaller communities had them, as well, usually at the fanciest place in town.

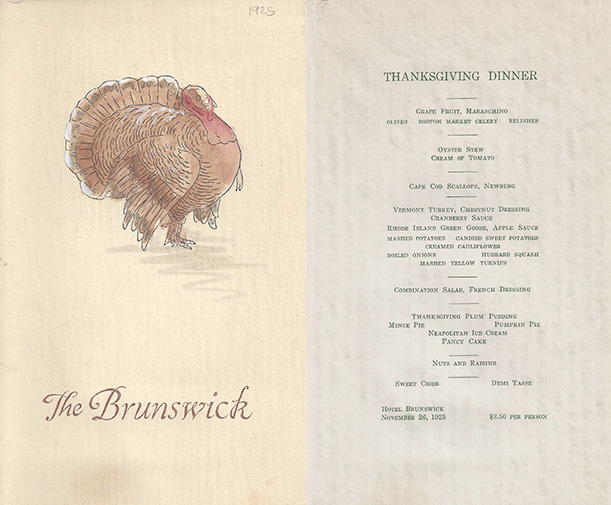

The 1925 menu from the Brunswick Hotel. The cost? $3.50 per person

The Waldorf, which opened in 1893, probably gets the prize for the most outrageous celebration. In 1915, the hotel erected an elaborate, mock “New England barn” in its grillroom for Thanksgiving Day—complete with, if the press reports are true, live animals and a dancing scarecrow. Well-heeled, urban diners feasted and danced, paying an odd tribute to the rural, New England roots of the holiday. As garish as it may sound today, the event was a smash.

“The Thanksgiving Day revel attracted one of the largest crowds that ever attended an affair at the hotel,” gushed The New York Times.

What changed all that? Baker thinks it was the combination of Prohibition in the 1920s and the Great Depression of the following decade. While some restaurants continued to offer grand Thanksgiving Day dinners, the practice had declined to the point that by the mid-20th century, as Rockwell’s painting suggests, it seemed almost un-American to have Thanksgiving Dinner anywhere but around grandma’s table.

“When my father came back from World War II, he was going to have nothing but the full homemade Thanksgiving dinner around the family table,” recalls Peggy Baker with a laugh. “He did relent enough to let my mother buy a pie from the store…that’s only because she wasn’t good at making pies.”

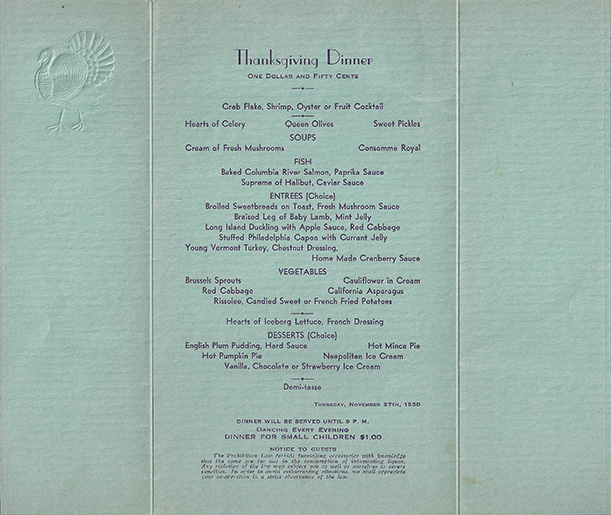

The 1930 menu from the Elks Hotel on Queens Boulevard in Elmhurst, Long Island, New York

But some say that in the 21st century, dining out on Thanksgiving could be in again. In a 2011 survey, the National Restaurant Association found that 14 million Americans dined out on Thanksgiving; and anecdotal evidence suggests that more restaurants are open for the holiday, to accommodate greater demand.

“It is still a very domestically oriented holiday,” O’Neill says, “but I think now, especially with smaller families or families that are spread out a lot, it is much more fluid and adaptable. Whether it’s at the family home, or someone else’s home, or a restaurant, it’s now more of a ‘let’s just sort of have a big dinner’ holiday.”

Although probably not one with turtle soup and duck liver on the menu.