Velázquez: Embodiment of a Golden Age

The magic of Velázquez has influenced artists from his contemporaries to Manet and Picasso

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Velazquez-portrait-388.jpg)

As a teenage art student at Madrid’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1897 and 1898, Pablo Picasso haunted the galleries of the Prado Museum, where he liked to copy the works of Diego Velázquez. Picasso was especially fascinated by Las Meninas; in 1957, he would produce

a suite of 44 paintings reinterpreting that single masterpiece. And he was hardly alone among 19th- and 20th-century painters: James McNeill Whistler, Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, Salvador Dali and Francis Bacon were all profoundly influenced by the 17th-century Spanish master. Édouard Manet, the pioneering French Impressionist, described Velázquez as “the painter of painters.”

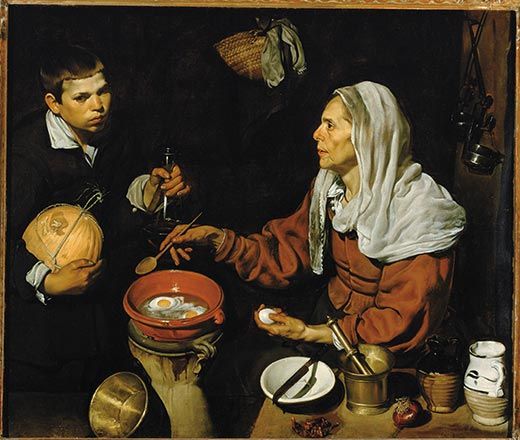

Born in Seville in 1599, Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez was the very embodiment of Spain’s artistic golden age. He painted noblemen and commoners, landscapes and still lifes, scenes from the Bible and classical mythology, court jesters and dwarfs, a young princess in formal dress, an old woman cooking eggs, and at least one sensuous nude. Unusual for its time and place, the Rokeby Venus was slashed in London’s National Gallery in 1914 by a militant suffragist (it was later restored). What makes Velázquez extraordinary, however, is less the range of his subject matter than his marriage of technical prowess and honest expression. When Pope Innocent X first saw Velázquez’s portrait of him in 1650, he is said to have remarked, simply, “Troppo vero” (“Too true”).

“Part of the magic in looking at Velázquez—and it is magic—is the astonishing level of verisimilitude that he achieves, combined with a general befuddlement as to how he achieves it,” says Philippe de Montebello, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who now teaches at New York University. “There is nothing about Velázquez that is overt, obvious, vulgar or excessive. It’s hard to imagine that anybody ever handled paint as brilliantly as he did.”

His talent blossomed early. Apprenticed at 11 or 12 to a locally prominent instructor in Seville, Velázquez was licensed to establish his own studio at 18. His earliest works often depicted religious scenes. Yale’s The Education of the Virgin is thought to have been painted in this period. In 1623, Velázquez came under the patronage of the Spanish monarch Philip IV and received the first of several royal appointments that would continue until the artist’s death, at age 61, in 1660.

Although Velázquez served the powerful, his respect for human dignity knew no rank. The celebrated portrait Juan de Pareja expresses the inner nobility of his longtime servant and assistant. When Velázquez painted a dwarf kept for the amusement of the royal court, he did not emphasize what other artists saw as a deformity. “Under the brush of Velázquez,” de Montebello says, “it’s the humanity, the empathy, that comes through. But not in a sentimental way—always on a very high plane, and with a certain level of gravitas.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)