The Robot Revolution Is for the Birds

Look up for robotic ravens and cyborg pigeons

![]()

Human flight has become boring. Air travel is a testament to man’s ingenuity and imagination. In the words of comedian Louis CK, “you’re siting in a chair – IN THE SKY.” It’s amazing. And yet, in only 50 years or so, flight, something scholars and inventors have been investigating for centuries, has become a banality. Sometimes, even an inconvenience! And though we may have mastered the skies to the extent that unmanned aerial vehicles can be sent anywhere on the planet, there is still some mystery left to discover. For while drone technology may seem to be the only area where advancements in flight are being made, many researchers today, like Archytas and da Vinci before them, remain fascinated by something that seems much simpler: bird flight, and by the possibility of creating unmanned aerial vehicles of a very different nature.

Take for example, SmartBird (top image) a project developed 2011 by Festo, a global leader in automation technology. Inspired by the herring gull and the book Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Smartbird is a robot with articulated wings that function just like their biological inspiration, generating thrust and forward motion. With Smartbird, researchers wanted to decode bird flight to develop a machine that could take off, fly, and land using only its own wing-flapping power. The “mechatronic and cybernetic holistic design” was made possible by using lightweight construction materials and a unique mechanism that allows the wings to twist and torque in a way that approximates real birds. SmartBird is not necessarily the future of aviation, but was created as a proof-of-concept for technology that may one day be used to help create more efficient factory automation and new power generators. However, it’s natural flight movements and seagull “disguise” seem to imply more tactical uses.

More recently, researchers at the University of Maryland Robotics Center have successfully launched a “micro air vehicle” that has been in development for eight years. After many test flights, many crashes, and many adjustments, the Robo Raven, as it is known took to the skies for the first after the team made a design breakthrough in April. Their new design features programmable wings that can be controlled independently, like real bird wings, allowing for high velocity dives, rolls, and other aerial acrobatics. The silver mylar-winged robot is much smaller and much more abstract in appearance than the SmartBird, but its movement is incredibly realistic. So realistic in fact, that it has even fooled nature – several early models were torn apart by hawks. It’s really quite something to see. The project’s success was also made possible by recent advancements in manufacturing like 3D printing and laser cutting. The Maryland team suggest that one day, the relatively lightweight, cheap, and versatile technology of robot birds could potentially be used for agriculture and environmental monitoring. There are other possibilities as well, including surveillance – Robo Raven has already been outfitted with a POV camera. If these robotic birds become natural enough, the drones of tomorrow could be undetectable to the untrained eye.

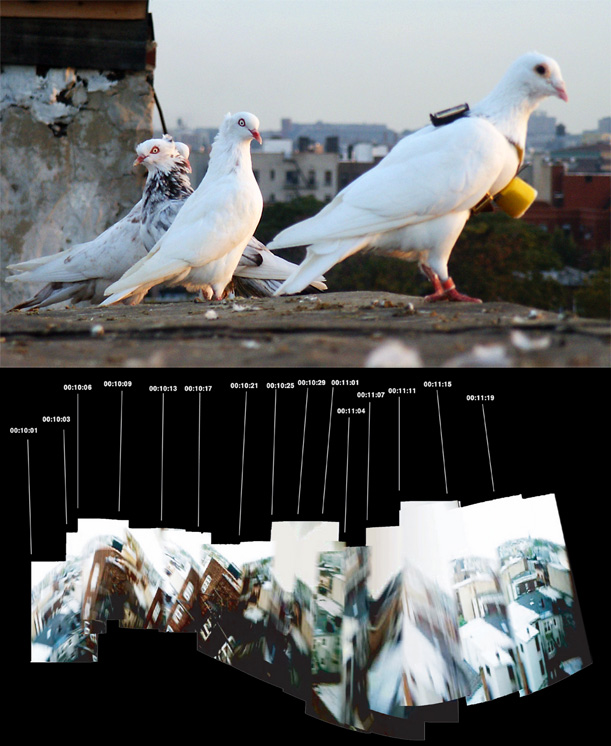

But you don’t need drones or robots to survey of a city from the skies. New York architects Aranda\Lasch have shown that cyborg pigeons will do just fine.

Aranda\Lasch developed The Brooklyn Pigeon Project as an experimental biological satellite. A flock of trained pigeons, ubiquitous in New York City, were equipped with a small battery, video camera, and microphone, and flown in spiral patterns over Brooklyn. The project is both a documentation of flocking behavior and an attempt to craft a true birds-eye view of the city. The avian cartographers of the Brooklyn Pigeon Project are sensitive to environmental stimuli that their human counterparts can’t observe. Their flight patterns are affected by sound, smells, and their ability to sense the Earth’s magnetic field form. The resulting maps differ dramatically from the purely technological “grid” of modern GIS systems to provide a unique perspective on the city that, in the words of the designers, “contrasts directly with the way the city is increasingly recorded and represented today.”

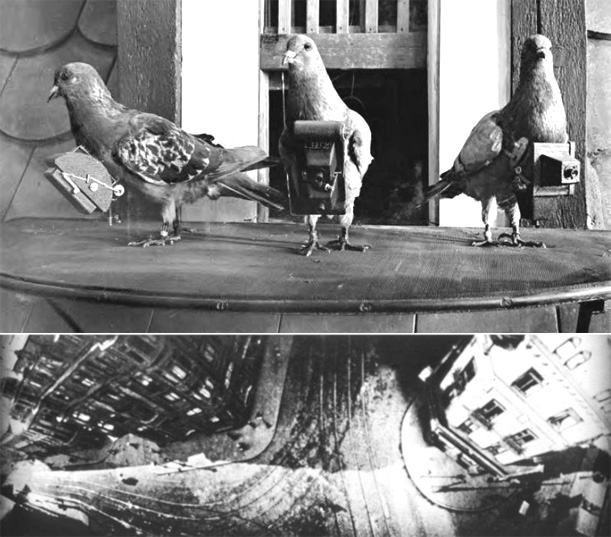

Top image: Julius Neubronner’s pigeon cameras. Bottom image: a photo taken from a pigeon (image: wikipedia)

The Brooklyn Pigeon Project has a precedent in the work of pharmacist, inventor, and amateur photograph by the name of Julius Neubronner who, between 1907 and 1920, developed dozens of miniature cameras designed to be attached to carrier pigeons via tiny leather harnesses. While initially created as little more than a hobby, Neubronner anticipated that his invention would have military uses and indeed his pigeon photographers were briefly enlisted and deployed to safely take photographs over enemy lines (part of an ongoing effort to militarize animals, as noted in ion’s history of animal soldiers). Although slightly more unweilding than the BPP cameras, Neubronner’s device is perhaps more ingenious.

It’s exciting to think that the avian world still has much to teach us. We still strive to capture the world as experienced by birds – the way they so elegantly move thorough the skies, see the ground, and detect the invisible forces that surround us. New research, combined with new manufacturing technologies, is bringing us a little closer to the day when the familiar airplanes and intimidating drones filling our skies will be replaced by autonomous, naturally flying, all-seeing, robotic birds. Despite centuries of investigation, we’ve only just started to unlock the secrets that nature perfected over eons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)