Shark Fin Soup in Hot Water

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110920113012shark-fin-soup.jpg)

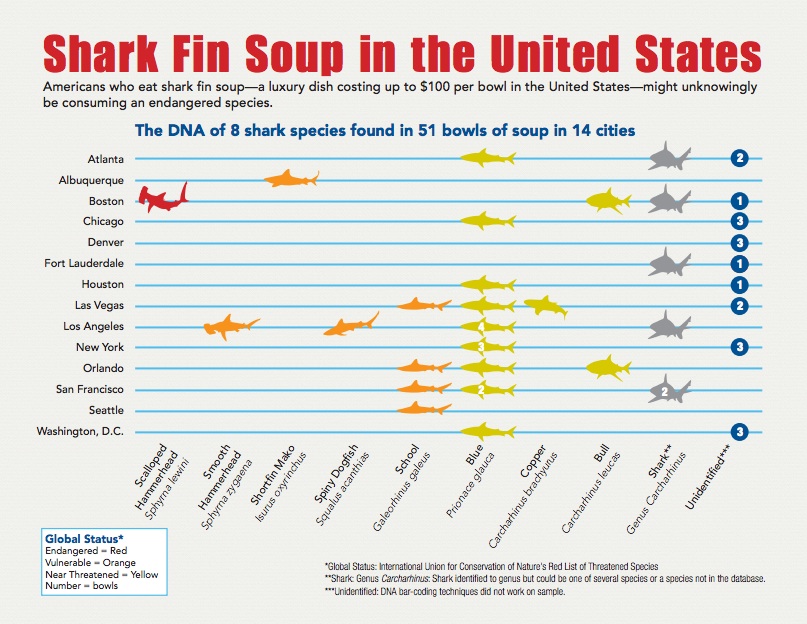

California is on the road to becoming the fourth state in the union to ban shark fin soup on account of the ecological impact that rising demand is having on shark populations. A bill nixing the sale, trade or possession of shark fins passed the state senate on September 6 and is awaiting governor Jerry Brown’s signature to be passed into law. The namesake ingredient for this Asian delicacy is harvested by fishermen who catch sharks, remove the fins and dump the carcasses back in the ocean. While other parts of the shark are edible or can be used for other purposes, it makes more financial sense for the fishermen to haul back the fins because they are the most valuable: they can sell (depending on size and the species of shark) for upwards of $880 per pound on the Hong Kong market. (In 2003, a fin from a basking shark sold for $57,000 in Singapore.) It is estimated that between 26 and 73 million sharks are killed worldwide each year for their fins, and with sharks unable to reproduce at such a rate to meet human demand, sustainable shark fishing is a bit unrealistic.

So what’s the big to-do over this dish? It’s certainly not the fin’s flavor—which has been described as being relatively tasteless—but rather it’s unique, rubbery texture. Once dried, processed and incorporated into the soup, the fin looks like fine, translucent noodles whose culinary value is in their mouthfeel—all the flavor has to come from the other soup ingredients. Some chefs have tried using gelatin-based substitutes, but, for those intimately familiar with the dish, imitation shark falls short of capturing the feel of the real deal.

Braised shark's fin soup with fresh crab meat. Image courtesy of Flickr user Sifu Renka.

“This is the most stunning aspect of the entire economic empire that has arisen around shark’s fin soup” environmental reporter Juliet Eilperin writes of the soup in her book Demon Fish. “It is, to be blunt, a food product with no culinary value whatsoever. It is all symbol, no substance.” Indeed, with some iterations costing upwards of $100 a bowl, it’s a dish that, if nothing else, displays one’s social status.

The dining tradition that dates back to the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 A.D.), becoming a mainstay of formal dining during the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644 A.D.), and it continues to be a popular dish at Chinese weddings. Opponents see the ban as an act of cultural discrimination, with the language of the bill singling out shark fin soup and giving no mention of other shark-based products, such as steaks or leather goods.

But shark populations are declining. In the 1980s, Hong Kong’s local shark populations were overfished to the point that its fishing market went bust. In the U.S., dusky shark numbers have declined by roughly 80 percent since the 1970s, with conservationists estimating that it would take upwards of 100 years for those populations to rebuild. In western Atlantic waters, hammerhead sharks have declined by up to 89 percent over the past 25 years. And in spite of cultural traditions, the international community—with the exceptions of Japan, Norway and Iceland—has placed bans on whaling because humans put such a strain on those populations. Should the same reasoning be applied to sharks?