A Scottish Duke Transformed This Abandoned Coal Mine into a Cosmological Land-Art Park

A scarred landscape in rural Scotland has become a grassy multiverse now open for exploration

Open-pit coal mining has turned parts of rural Scotland into desolate, denuded eyesores. The collapse of the industry and the ensuing economic downturn has also made it hard for local governments to justify spending millions to redevelop these sites. In such cases, it helps if the site is owned by Richard Scott, the tenth Duke of Buccleuch, because he might just call on one of his land-art buddies to turn it into a modern-day Stonehenge, and foot the bill himself. Which is exactly what he did to create the just-opened Crawick Multiverse, a 55-acre land-art park outside the town of Sanquhar, designed by artist and landscape architect Charles Jencks.

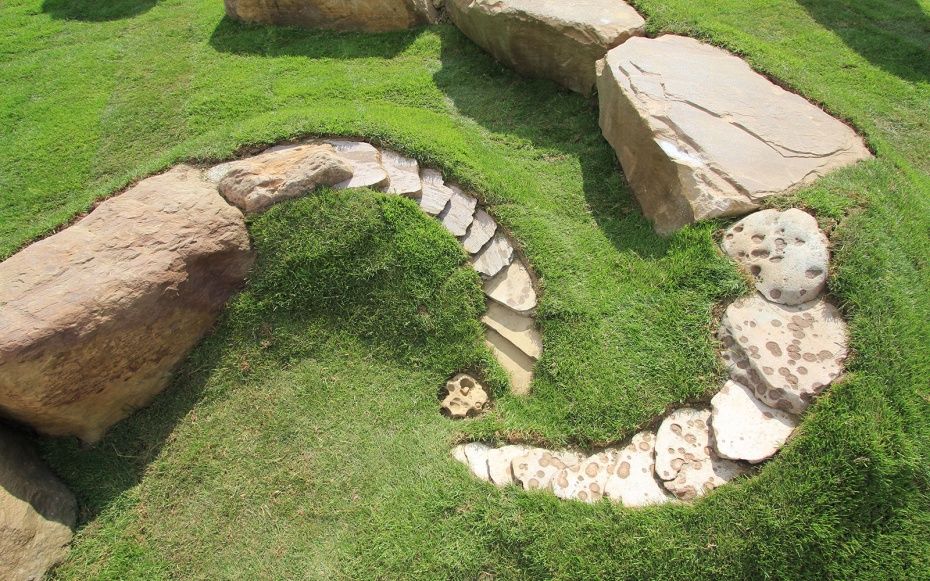

Jencks creates land art with a cosmological bent that fits nicely with the U.K.'s prehistoric standing-stone arrangements, many of which are believed to have functioned as astronomical calendars. At the Crawick Multiverse, Jencks took a pair of hills created when polluted earth was removed from the site and sculpted them with spiraling paths, representing the Andromeda and Milky Way galaxies. There's also a "comet walk," a "supercluster" of triangular mounds, and a mudstone path carved with figures representing different theoretical arrangements of the universe, all decorated with some 2,000 boulders found on the site.

"This former open cast coal site, nestled in a bowl of large rolling hills, never did produce enough black gold to keep digging. But it did, accidentally, create the bones of a marvelous ecology," says Jencks. "The Multiverse celebrates the surrounding Scottish countryside and its landmarks, looking outwards and back in time to present a difference view of the situation we are in. Its view is much more open than, say, that of a clockwork universe, and much more interesting—a different sort of landscape."

Jencks worked with the ridges and furrows of the mining site, rather than completely reshaping them, so in a sense, his work is a kind of post-industrial found art. One pragmatic benefit of working this way is the money you save on landscaping. Construction began in 2012, and by the time it wrapped up, it had only set Smith back a reported £1M. Which is a bargain, as he points out, in today's art market.

Hear more about the work from the artist:

More Stories from Travel+Leisure: