Rug-of-War

For nearly thirty years, Afghani weavers have incorporated images of war into hand-woven rugs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/afghan-rug-631.jpg)

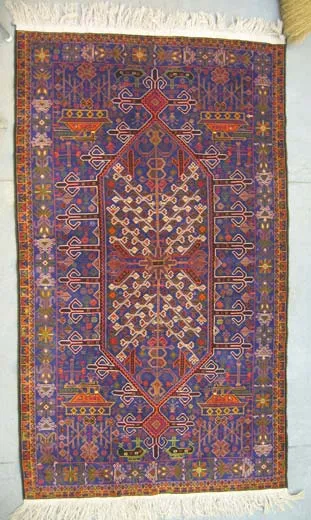

Attorney Mark Gold has an oriental rug in his western Massachusetts home that most people call "nice-looking" until he tells them to inspect it more closely. Then they're enthralled, because this is no run-of-the-mill textile—it's what is called an Afghan war rug, and what it depicts is somber and stunning: cleverly mixed with age-old botanical and geometric designs are tanks, hand grenades and helicopters. "It's a beautiful piece in its own right," says Gold, "but I also think telling a cultural story in that traditional medium is fascinating."

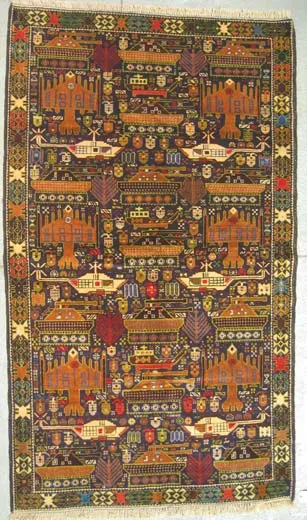

The cultural story Gold's rug tells is only the beginning. Since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the country's war rugs have featured not only images of the instruments of war, but also maps detailing the Soviet defeat and, more recently, depictions of the World Trade Center attacks.

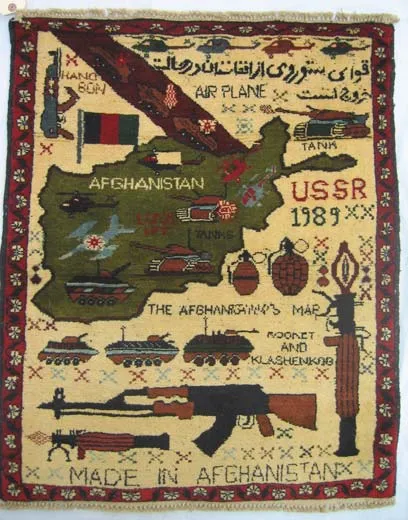

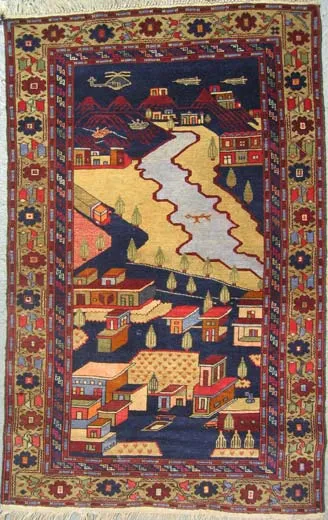

It was women from Afghanistan's Baluchi culture who, soon after the arrival of the Soviets, began to weave the violence they encountered in their daily lives into sturdy, knotted pile wool rugs that had previously featured peaceful, ordinary symbols, such as flowers and birds. The first of these rugs were much like Gold's, in that the aggressive imagery was rather hidden. In those early years, brokers and merchants refused to buy war rugs with overt designs for fear they would put off buyers. But with time and with the rugs' increasing popularity, the images became so prominent that one can even distinguish particular guns, such as AK-47s, Kalashnikov rifles, and automatic pistols.

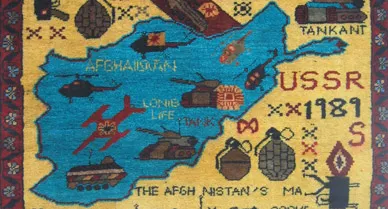

A decade later, the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan, and rugs celebrating their exodus appeared. Typical imagery includes a large map with Soviet tanks leaving from the north. These rugs, principally woven by women of the Turkman culture, often include red or yellow hues and are peppered with large weapons, military vehicles and English phrases such as "Hand Bom [Bomb]," "Rooket [Rocket]" and "Made in Afghanistan."

To many, this script is a firm indication of the rugs' intended audience: Westerners, and in particular, Americans, who funded the Afghan resistance—the Mujahadeen—during the Soviet occupation. "The rugs are geared for a tourist market," says Margaret Mills, a folklorist at Ohio State University who has conducted research in Afghanistan since 1974. "And they verbally address this market." Sediq Omar, a rug merchant from Herat who dealt in war rugs during and after the Soviet occupation, agrees. "Afghanis don't want to buy these," he says. "They're expensive for them. It's the Westerners who are interested."

While this may be true, it's likely that the first "hidden" war rugs from the early 1980s were meant for fellow Afghanis, according to Hanifa Tokhi, an Afghan immigrant who fled Kabul after the Soviet invasion and now lives in northern California. "Later on, they made it commercialized when they found out that people were interested," she says. "But at the beginning, it was to show their hatred of the invasion. I know the Afghan people, and this was their way to fight."

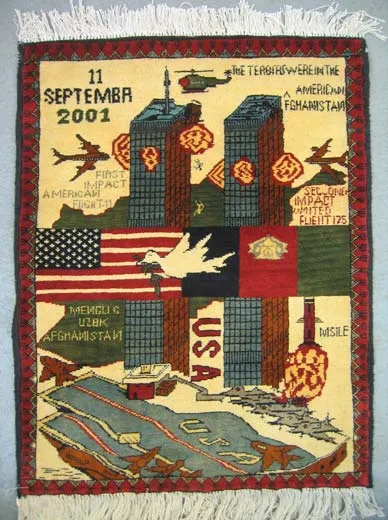

The war rug's latest form shows the demise of the World Trade Center, and many Americans find it upsetting. After September 11, Turkman weavers began to depict the attacks with eerie precision. Planes strike the twin towers with accompanying text declaring "first impact" and "second impact," and small stick figures fall to their deaths. Jets take off from an aircraft carrier at the bottom of the rug, and just above, a dove with an olive branch in its mouth seems to unite American and Afghan flags.

Kevin Sudeith, a New York City artist, sells war rugs online and in local flea markets for prices ranging from $60 to $25,000. He includes the World Trade Center rugs in his market displays, and finds that many passersby are disturbed by them and read them as a glorification of the event. "Plus, New Yorkers have had our share of 9/11 stuff," he says. "We all don't need to be reminded of it." Gold, a state away in Massachusetts, concurs. "I appreciate their storytelling aspect," he says. "But I'm not there yet. It's not something I'd want to put out."

Yet others find World Trade Center rugs collectable. According to Omar, American servicemen and women frequently buy them in Afghanistan, and Afghani rug traders even get special permits to sell them at military bases. Some New Yorkers find them fit for display, too. "You might think it's a ghoulish thing to own, but I look upon it in a different way," says Barbara Jakobson, a trustee at Manhattan's Museum of Modern Art and a longtime art collector. "It's a kind of history painting. Battles have always been depicted in art." Jakobson placed hers in a small hallway in her brownstone.

In an intriguing twist, it turns out the World Trade Center rugs portray imagery taken from U.S. propaganda leaflets dropped from the air by the thousands to explain to Afghanis the reason for the 2001 American invasion. "They saw these," says Jakobson, "and they were extremely adept at translating them into new forms." And Nigel Lendon, one of the leading scholars on Afghan war rugs, noted in a recent exhibition catalog that war rug depictions—both from the Soviet and post-9/11 era—can be "understood as a mirror of the West's own representations of itself."

If Afghanis are showing how Americans view themselves via World Trade Center war rugs, Americans also project their views of Afghan culture onto these textiles. In particular, the idea of the oppressed Muslim woman comes up again and again when Americans are asked to consider the rugs. "Women in that part of the world have a limited ability to speak out," says Barry O'Connell, a Washington D.C.-based oriental rug enthusiast. "These rugs may be their only chance to gain a voice in their adult life." Columbia University anthropology professor Lila Abu-Lughod takes issue with this view in a post-9/11 article "Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?" She notes the importance of challenging such generalizations, which she sees as "reinforcing a sense of superiority in Westerners."

Whether in agreement with Abu-Lughod or O'Connell, most conclude that the women who weave Afghan war rugs have a tough job. "It's very hard work," says Omar. "Weavers experience loss of eyesight and back pain—and it's the dealers who get the money."

But as long as there's a market, war rugs will continue to be produced. And in the U.S., this compelling textile certainly has its fans. "These rugs continue to amaze me," says dealer Sudeith. When I get a beautiful one, I get a lot of pleasure out of it." And Gold, who owns five war rugs in addition to the hidden one he points out to visitors, simply says, "They're on our floors. And we appreciate them underfoot."

Mimi Kirk is an editor and writer in Washington, D.C.