A New Edition of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ Crosses Its T’s and Dots Its I’s

Barbara Heller used period handwriting—and new material—to bring the novel’s colorful letters to life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/86/6d86851e-ef7a-485d-ba95-3e28d5e4f2fc/jane_austen_1.png)

In Jane Austen's Emma, the title character's rival Jane Fairfax marvels at the efficiency of the mail: "The post-office is a wonderful establishment!" she declares. "The regularity and despatch of it! If one thinks of all that it has to do, and all that it does so well, it is really astonishing!"

The regularity of the mail in Austen's novels is often the heart of the story. Indeed, it is generally agreed that Austen's most famous work, Pride and Prejudice, began as an epistolary novel called First Impressions, consisting exclusively of letters between the characters. The epistolary novel was one of the main traditions from which Austen's remarkable realism emerged, and in each of her six full-length novels, letters serve (quite naturally) as crucial points in developing plot and character. To imagine an Austen novel without letters would be, to borrow a word from Jane Fairfax, astonishing.

Now, Barbara Heller, a set decorator for film and television, has curated a special edition of Pride and Prejudice that offers readers handwritten reproductions of the 19 letters that appear in the novel, artfully rendered by calligraphers at the New York Society of Scribes. Turn to Chapter VII in the first volume, for instance, and you'll find a sleeve enclosing two letters: one from the fancy Caroline Bingley, inviting the more modest Jane Bennet to luncheon at lavish Netherfield Hall, and a subsequent note from Jane, informing her younger sister Elizabeth that she has caught a cold en route to Netherfield. The two letters are written in visibly different styles of handwriting—which is exactly what Heller had in mind when she set out on the project.

"Austen herself correlated handwriting with character," says Heller. "I thought Jane Bennet would have sweet, pretty handwriting, and we know from the novel that Mr. Darcy writes in a really even hand, and Caroline Bingley writes in a very flowing hand."

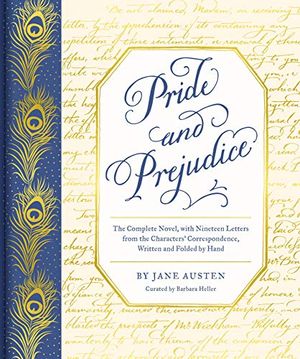

Pride and Prejudice: The Complete Novel, with Nineteen Letters from the Characters' Correspondence, Written and Folded by Hand (Handwritten Classics)

For anyone who loves Austen, and for anyone who still cherishes the joy of letter writing, this book illuminates a favorite story in a whole new way.

But Heller and her band of scribes didn't rely just on Austen's descriptions. Heller spent months at New York City’s Morgan Library perusing its archive of English correspondence written between 1795-1830 and selecting handwriting examples that seemed to capture the essences of various characters from Pride and Prejudice. For example, to model Mr. Darcy's handwriting, Heller chose a series of letters from the Duke of Kent (Queen Victoria's father) to General Frederick Weatherall. "These lovely, long letters," Heller says, seemed to capture at once the moral rectitude and lively mind of Austen's fictional patrician hero. Meanwhile, for the Bennet sisters' uncle, Mr. Gardiner, Heller selected Robert Southey, poet laureate of England for 20 years (and one of Lord Byron's favorite literary targets.)

"Southey had this very neat, pointy writing, very even lines" Heller says. "He kept a very clean margin, and it really clicked to me for Mr. Gardiner.

And for the most important handwriting of all—that of Elizabeth Bennet, the novel's heroine—Heller chose Austen's own hand as a model.

Of course, only some of the letters in the original novel appear in their full length. Others we read in snatches, and some we don't read at all—we get them only in paraphrase. Heller's task, then, was not limited to managing a group of calligraphers. She also had to write original material that sounded as though Austen had written it. Many writers would have thrown in the towel after a day.

"It was completely agonizing," Heller says, "because I felt like I was adding words to a beloved classic. It felt like an act of hubris." Various helpers—including her two sisters, who are big Austen fans—lent their aid in composing the missing text in the letters. "Some of [the new material] is cribbed from Austen's own letters," Heller says, while elsewhere the task was one of "taking what was paraphrased [in the novel] and turning it into letter prose."

Fans of the original, even particularly exacting fans, will likely be impressed with Heller's achievement. The new material is in keeping with the characters who wrote them, and with the world of the novel those characters inhabit. That sense of immediacy is reinforced by the human error included in the letters. Calligraphers are used to writing flawless wedding invitations; in this case, Heller encouraged her scribes to set aside their usual perfectionism.

"They’re trained to write evenly and consistently," Heller says, "whereas I wanted them to write until the ink ran out, to strike out words, to add a carat and so forth."

Even beyond the minute care taken in the handwriting, the letters in Heller's edition of Pride and Prejudice are painstakingly detailed, from the style of folding (letters didn't have envelopes, so they served as their own containers) to the postal markings and wax imprints indicating price, mileage, date, etc. Alan Godfrey of the Association of British Philatelic Societies counseled Heller on the finer points of how the post operated during Austen’s time, and you can see the resulting details in this annotated version of Mr. Collins' final letter to the Bennets:

And just as these letters, with the various character traits that their appearances indicate, can bring 21st-century readers closer to Austen's world, Heller says that the process of assembling the book has made her sensible of a deeper connection with Austen: "When I read Mr. Collins' letter, I experience Austen’s delight in writing it," she says. "Or maybe that’s just my delight in reading it."

Heller isn't quite done yet, though. More recently, she's been studying Louisa May Alcott's handwriting, as she prepares a similar edition of Little Women, wherein readers can enjoy the letters of that novel in the handwriting of a different country and period from Austen's. "I've already found some interesting Union Army stationery that can be used for some of the characters," she says.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.