Meet Molly Crabapple, an Artist, Activist, Reporter, and Fire-Eater All in One

With pen and brush, the talented journalist fights for justice in the Middle East, and closer to home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/0e/1d0e7524-6a86-40fe-b914-ad15bca447a9/apr2016_c01_colrosenbaumcrabapple-wr-v1.jpg)

In her 2013 book about Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive Era, The Bully Pulpit, Doris Kearns Goodwin celebrates the “muckrakers,” the crusading journalists who fought to correct long-standing injustices and change society. Many of them were women: Nellie Bly, who exposed the horrors of mental institutions; Ida Tarbell, who took on the monopoly power of Standard Oil; and Jane Addams, who shone a light on the misery of impoverished immigrants. Intrepid reporters who revealed realities that were so powerful that the facts alone were a form of activism.

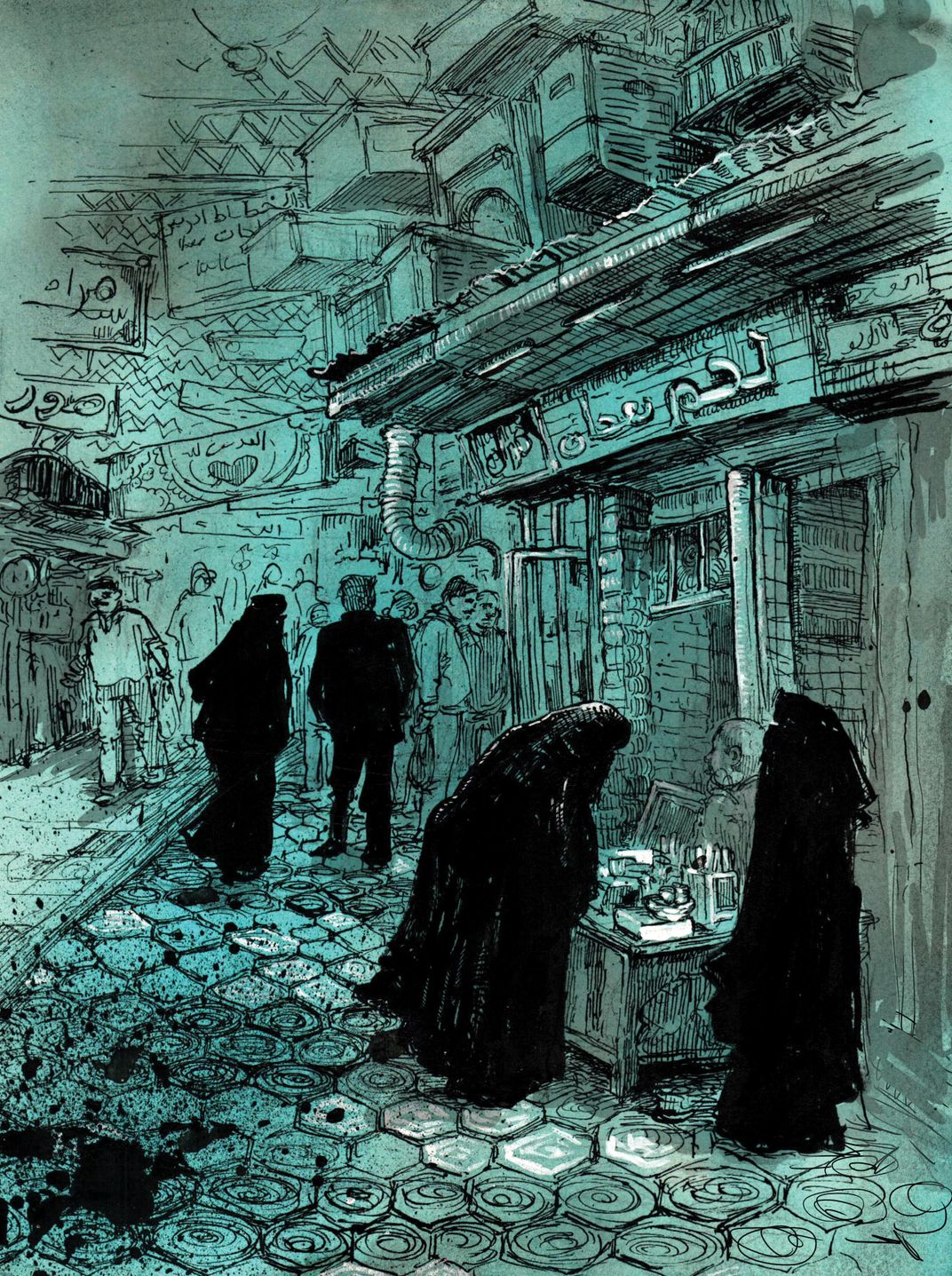

There is someone working today I think of in the same tradition, a fiery young woman—a former fire-eater, in fact—who is a reporter, artist and activist all rolled into one. She calls herself Molly Crabapple, she’s 32 and she has braved the hell of ISIS-plagued territory to report on the plight of Syrian refugees. She has dressed down in gritty work clothes to record the shocking conditions in immigrant labor camps in Abu Dhabi one day, and dressed up the next to swan through tight security at a Dubai press conference to confront Donald Trump about the low wages of workers building his glitzy new golf course and housing development. She has railed against the victimization of sex workers and dug up leaked videos from one of the worst “holes” in the American prison system in Pennsylvania to draw attention to the wretched souls incarcerated there. She’s traveled to Guantanamo, Gaza, Lebanon, Istanbul and riot-torn Athens.

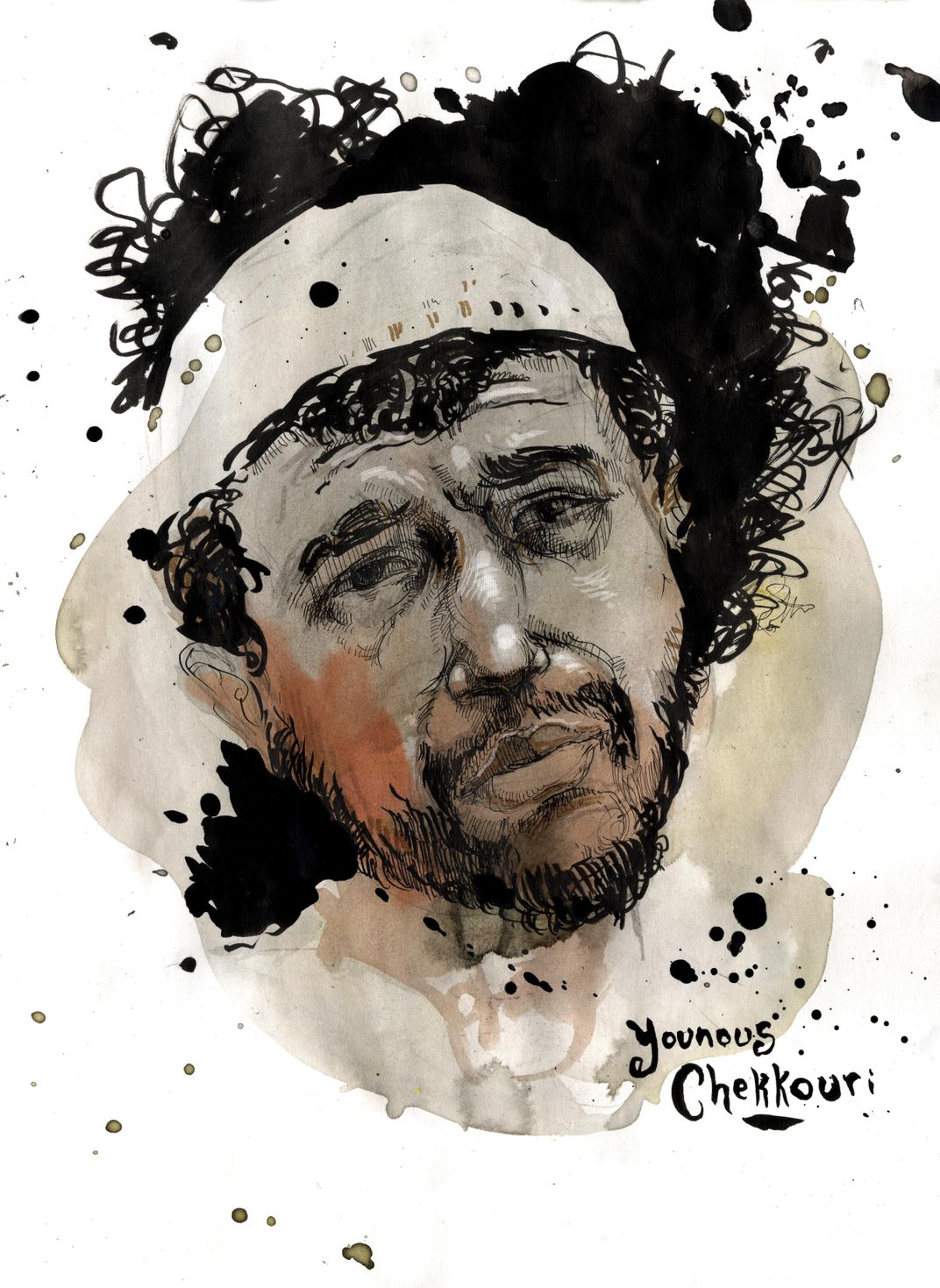

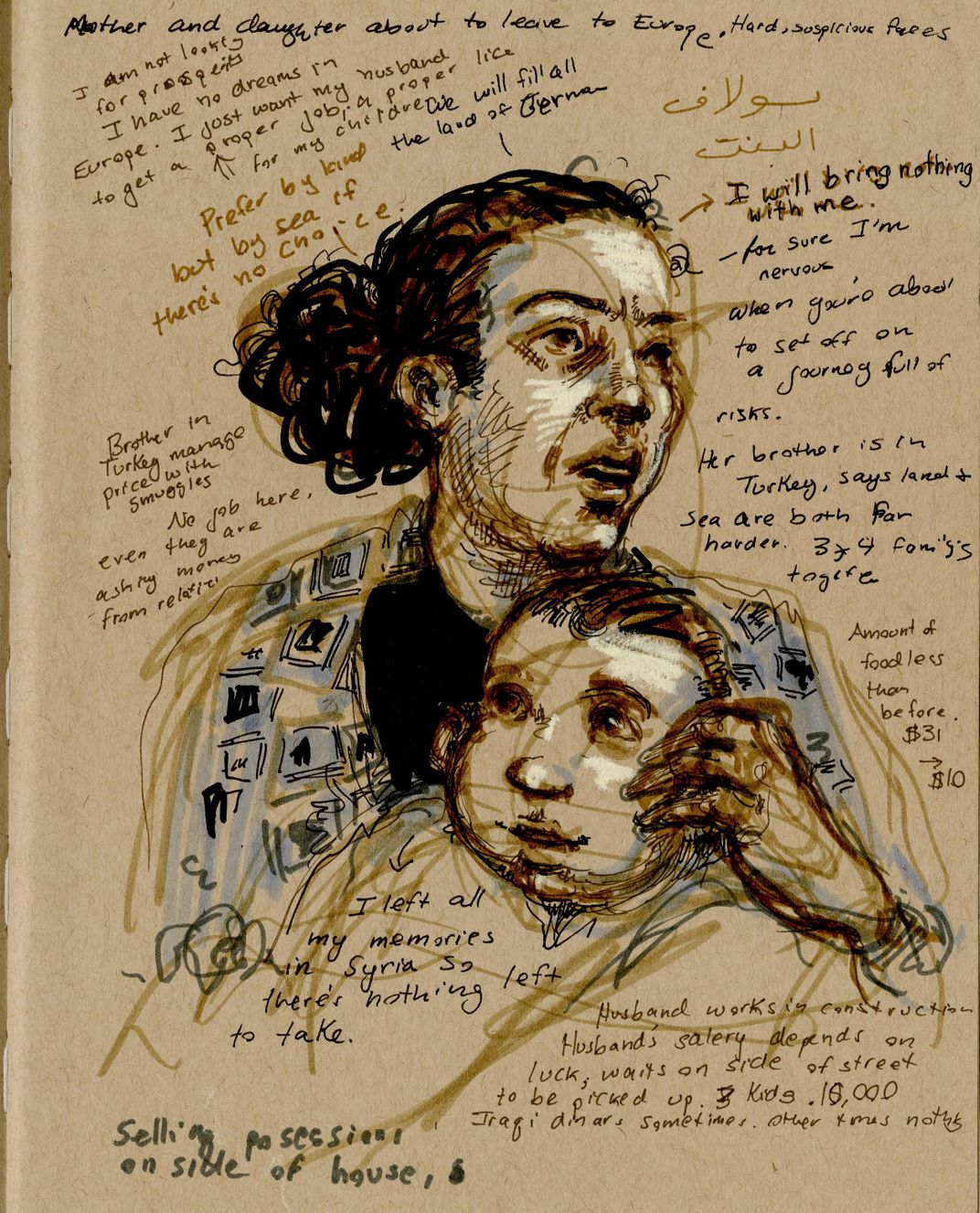

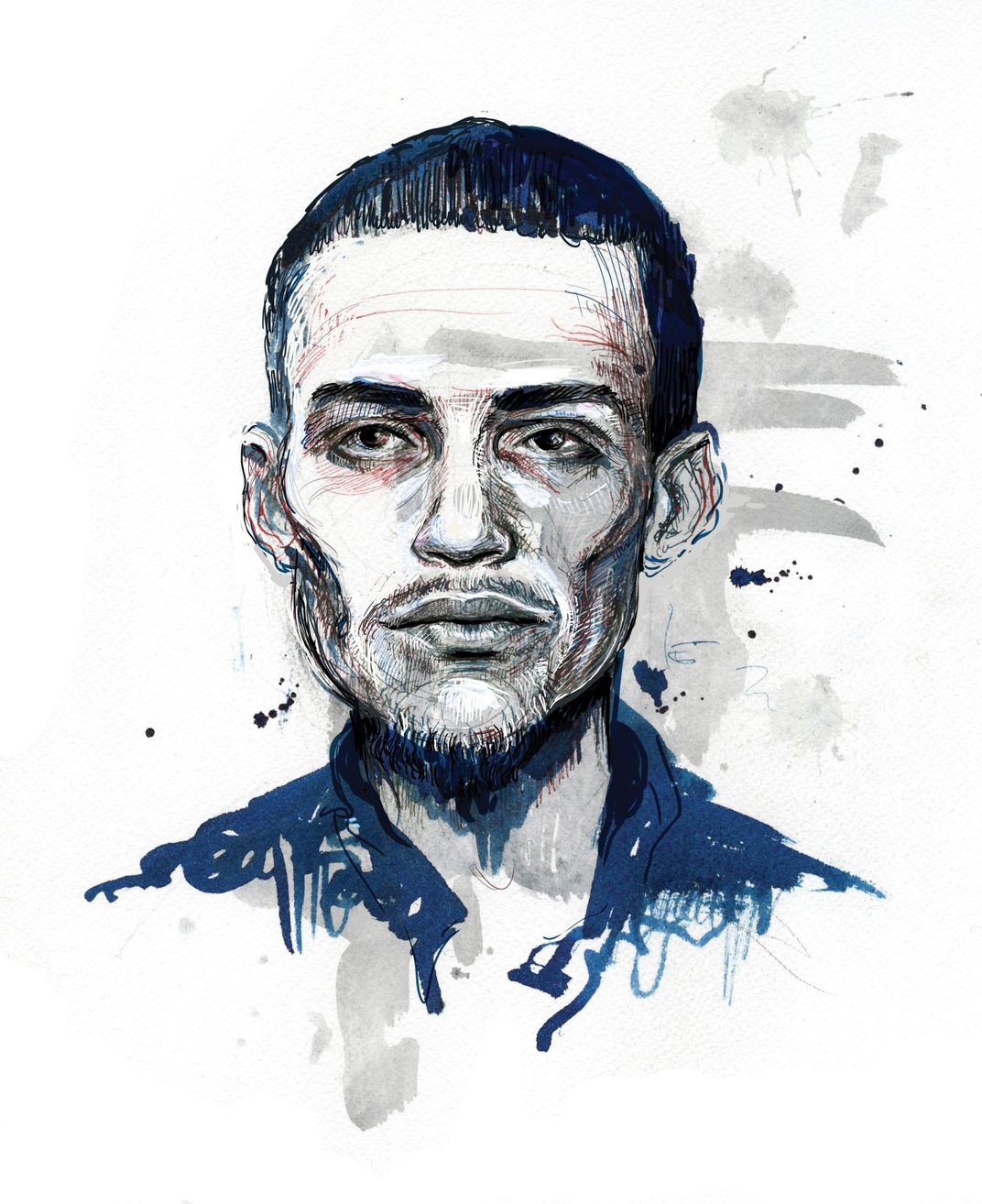

Unlike her predecessors, Crabapple makes her weapons of choice the artist’s pen and paintbrush. Her frenzied arabesque strokes recall the savagery of Daumier and Thomas Nast and Ralph Steadman, as well as the tenderness of Toulouse-Lautrec. She makes us look at what we don’t want to see—searing vistas devastated by war, cities in ruins, people in agony. This is what the female version of the gonzo spirit looks like today. Less self-absorbed, more empathetic. But still fueled by outrage.

As she puts it, “There are so many photos from Syria of every possible atrocity—this is the most documented war in history—and people are kind of numb. You need to try to get people in the West to give a s--t. Drawing is very slow, it’s very invested.”

Her words and pictures appear in traditional media like the New York Times and Vanity Fair. But this barely scratches the surface of the dazzling array of projects by a woman who’s been called an art movement of her own. Her work has appeared in major galleries on three continents, she’s got a graphic novel and three art books to her credit, and she’s recently established herself as a writer with a blazing memoir called Drawing Blood. One reviewer has called her “a punk Joan Didion, a young Patti Smith with paint on her hands.”

And then there are the unique stop-motion drawings she posts to cutting-edge digital video platforms like Fusion. I’ve never seen anything like them before; they are mesmerizing. The speed sketching gives the images dramatic energy and the stories a memorable impact. The story of the Chinese computer engineer, for instance, who’d been living in America for 17 years and was married to an American citizen, but whose green card renewal paperwork was screwed up. Suddenly, immigration agents arrested him and threw him into a detention center a couple of thousand miles from home, with no access to desperately needed medicine. He died of bone cancer before he had a chance to make his case.

Crabapple’s activist side benefits from her social media expertise. She sells original pages from her animations, advertising them on Twitter, to raise money to aid Syrian refugees.

If you were to ask me how to sum up her impact, I’d say that it has to do with the so-called “economy of attention.” She focuses our minds, now so scattered and divided, on serious, heart-wrenching global issues.

**********

Most people don’t think of Wall Street as a residential neighborhood, but there are still a few small, scattered centuries-old apartment buildings bravely weathering the floods that battered financial district skyscrapers. The location of Crabapple’s apartment, not far from the famous bronze bull, turned out to be the catalyst for a turning point in her life.

She grew up a long subway ride and a world away, in Far Rockaway and Long Island. Her Puerto Rican father was a Marxist professor; her Jewish mother was a book illustrator. (Her given name was Jennifer Caban.) She was a rebellious goth brat, reading the Marquis de Sade and Oscar Wilde, and found herself inspired by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and his partner, the artist Frida Kahlo.

She reincarnated herself more than once, evolving from art student to artist’s model to performer and impresario of a kind of underground bohemian performance-art burlesque/circus scene in downtown New York. An ex-boyfriend chose the name “Molly Crabapple” for her. “He said it fit my personality,” she says, laughing.

She has been a whirlwind. But all was quiet as we sat at her cluttered kitchen table. She has a Scheherazade kind of beauty, which matches her apartment, decorated in a thrift-store Ottoman style.

I began by observing that some of the most daring reporting on the current catastrophe of the Middle East has been done by women, often freelancers, risking life and kidnapping and worse. Writers like Ann Marlowe, photojournalists like Heidi Levine and the late Anja Niedringhaus.

“There’s a legacy of women doing conflict reporting,” Crabapple replied. “Women like Nellie Bly and Djuna Barnes. They’ve been underestimated and written out of history by the men that control official narratives.

“When Djuna Barnes was a young woman, she endured force-feeding so she could write articles about what it was like for a suffragette hunger striker to be force-fed. Her first job was a journalist—and she was an illustrator as well. Then, of course, there’s Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s third wife, who went onshore on D-Day when women were banned from going to the front by sneaking onto a ship as a stretcher-bearer.”

“One thing it seems you’ve done in your work, which seems like it is in that tradition, is to shift the war zone narrative from the soldiers to the victims and refugees. Is that a conscious decision?”

“I think for some people it might seem sexier to hang out with the fighters because they have guns and it’s more photogenic with a young man with an AK-47. I’ve certainly interviewed fighters—I was with Islamic Front in Syria—but I’m interested in how war affects everyone. The war in Syria is probably the worst war in our century, and it’s causing a population displacement on par with what happened during World War II.”

This statement is, tragically, true: The United Nations recently reported that the Syrian civil war and conflict perpetrated by ISIS is now the world’s single largest cause of displacement, with some 12 million individuals driven from their homes.

“And I was interested in ground-level people—not necessarily victims. I feel like when you interview big muckety-mucks, whoever they are, you get prepackaged statements, a narrative that is very polished. If you want the truth, you speak to the people on the ground, whether that person is a grandma living in a refugee camp or a young fighter, or a cynical young man living in Aleppo.”

“Let’s pause for just a moment. Did you say you were with the Islamic Front?”

“Not the Islamic State. That’s a very important distinction. I was in Syria very, very briefly, and there was a coalition of groups that were Islamist groups that, at that time, had kicked ISIS out of a number of northern towns and was controlling the border crossing [into Turkey].”

“What were the Syrian rebel fighters like?”

“They were just young guys who had been in college. Obviously, since they work with the media, they’re very educated, they speak English. They were funny, sarcastic young men who had been through a lot of trauma and had seen too much. They had really seen too much.”

She recalls “one young guy who kept talking about seeing a C-section performed without anesthetic, at one of these makeshift field hospitals. And they’ve seen people die in bombings, they’ve killed people. One of the young guys I was with, he had killed several ISIS members. They’ve interrogated people; they’ve seen things that fundamentally change you as a person.”

“How does seeing so much horror affect you?"

“I guess you develop a sense of anger at the injustice of the world and the way people live and die according to the papers that they hold. But I feel silly talking about how it affected me and I’m here in a beautiful apartment. You know, what does it matter? It really affects the people who are living it.”

“Do you think your view of human nature has been changed by your exposure to all this suffering?”

“I’ve always been kind of cynical. But I think my view of human nature has been elevated because I’ve met so many people working in the most extreme adversity who are so decent and clever and fundamentally defiant, refusing to accept the roles that life has allotted to them. I have such admiration for people like that. I always feel I can learn from them, they’re people I feel very lucky to know and honor very much.”

I asked her where she’s been that she felt the most in danger.

“OK, there are these two neighborhoods in Tripoli [in Lebanon],” she remembers. “The best way to describe it is they’re like the Sharks and the Jets. Sunni militia and another group, which is Shia. And the neighborhoods have been fighting each other for 40 years, and there’s a street that divides them—they shoot over it, they throw grenades over it.

“So I did a piece for the New York Times about how Syrian refugees were fleeing Syria and going to Tripoli and still finding themselves amidst sectarian warfare, and I interviewed snipers in the local militias. I didn’t sketch them while they were shooting; I just sketched them in their little hide-outs.”

“Does anyone get killed in this or is it more a harassing kind of thing?”

“No, people were dying.”

“And these guys didn’t mind you...?”

“No, they were happy; they wanted to show off. They’re macho. This is something I find about getting access to a lot of stuff—people from all walks of life want to be acknowledged for what they do. And they don’t think what they do is bad at all. They’re quite proud of what they do. Like here’s my big gun, here’s my kid who I’m having throw grenades at people. It’s not just them. People from all cultures. You’ll find the same thing in America.”

I’ve often wondered about people who are drawn to witness suffering, sacrifice and survival. “Did you grow up feeling sensitive to suffering in some way?”

“I grew up in a very political house. My dad is a Marxist. He’s Puerto Rican and when I was a little girl he made up this story about this anti-colonialist pirate who would travel around the Caribbean and liberate slaves from sugar plantations. My dad came from a family of sugar cane cutters and became an academic. So I grew up in a household that was very concerned with injustice and very concerned with bulls--t. My dad told me when I was a little girl, ‘I have two rules for you: Question authority and be interesting.’”

“Well,” I said, “You managed that. You were a fire-eater at one point, weren’t you?”

Her performance art included a stint as a fire-eater. It struck me as a metaphor for her fire-breathing art. Of course, metaphors are fine, but I still found the actual fire-eating hard to believe. “How does that work?”

“OK,” she says, “fire-breathing is really hard but fire-eating is pretty easy.”

Who knew?

“So you take your torch...” She mimes holding a torch above her head, throwing her head back and dunking the burning end into her mouth.

“Your mouth isn’t going to get burned because the heat’s all going up, right?”

Um, sure.

“And then when you close your lips around the torch, it cuts off the oxygen and cuts off the flame.”

She is so nonchalant about it, she almost makes you forget what a crazy idea it is to eat fire.

**********

How did Molly Crabapple go from fire-eating downtown New York performance artist to flame-throwing journalist?

It started when she graduated high school early, at 17, traveled to Paris, got a job at the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore and fell in with the ex-pat Bohemian scene. She started drawing in a big notebook a boyfriend gave her, decided to learn Arabic, became intrigued by the Ottoman Empire and its art, and took off for far eastern Turkey.

There she became fascinated by a magically carved ruined palace. She had found her stylistic muse. “It’s on the Turkish-Armenian border,” she says, “and it’s so beautiful. It’s like this crazy, Dr. Seuss ruin with striped minarets and domes. [Back in New York] I spent long times sitting in Islamic rooms at the Met, staring at the miniatures, seeing how they did these subtle colors and detailed patterns. A lot of the reason why I admire art from the Islamic world is that in a lot of these countries figurative art is religiously prohibited, and so instead, they did the most intellectually rigorous but sensual abstraction in the world.”

“I like that: ‘Intellectually rigorous and sensual.’”

“Yeah, it’s like math, like math made into art.”

She pulls a book out of a pile on her kitchen table and opens to a page of intricate Islamic tile work. “Look at these patterned repetitions. It’s incredibly lush, but it’s based on math. All my sense of wonderment is aroused by this.”

In fact, she was so captivated by wonder at the arabesque forms in that mosque in eastern Turkey that she started sketching them in her notebook—and didn’t notice the police approaching to arrest her. She is characteristically blithe about the story. She remembers it as a great artistic experience, her first brush with the authorities; I think of Midnight Express. (After some suspicious questioning she was able to talk her way out it.)

But her real artistic turning point came during a frenzied period she calls her “Week in Hell”—a kind of artistic nervous breakdown. “I was just sick of my work,” she recalls. “I hated everything I had done. So I decided to lock myself in a hotel room, put paper over the walls and draw until I’d bled all of my clichés out of me and something new emerged.”

The project was later recorded in a graphic-novel-type book, both crazy and irresistible to look at, like a graffiti-covered New York subway car from the ’70s.

“You have said, ‘The wall broke me.’ What does that mean?”

“I had just drawn and drawn and drawn and drawn and finally I collapsed.”

And right after “A Week in Hell” ended, Occupy Wall Street started, just a few blocks away from her apartment. She was psychologically ready to throw herself into a movement that was larger than herself, she says. So she began doing a nearly 24/7 chronicle of Occupy, sketching the protests, clashes and arrests. One of her Occupy posters is now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

After Occupy left Wall Street she found herself drawn to seek out the world’s trouble spots, to report on the people whose every day was a week in hell. She persuaded Vice to send her to Guantanamo, from which she brought back harrowing images and reportage. Then she began to focus on the blood-soaked Middle East.

**********

Toward the end of our talk I asked about a quote I’d read of hers, something about her career trajectory: “Jaggedness,” she had said, “goads you on.”

She told me she didn’t have a big breakthrough success but a dozen or so cracks in the wall and just kept at it however jagged the path. “I didn’t have the easiest path to making the sort of life I wanted, and I certainly had a lot of rejection early on, as many artists have. A lot of people who didn’t believe in me, as many artists have. But I think that sort of pain, the parts of you that are a bit broken, are the parts of you that are most interesting in a lot of ways. They’re the parts of you that give you motivation to keep creating art and to keep fighting. That sort of chip on your shoulder can turn into a diamond, you know.”

“Is it still a chip or has it become a diamond?”

“I think it’s become a diamond now.”

Drawing Blood

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)