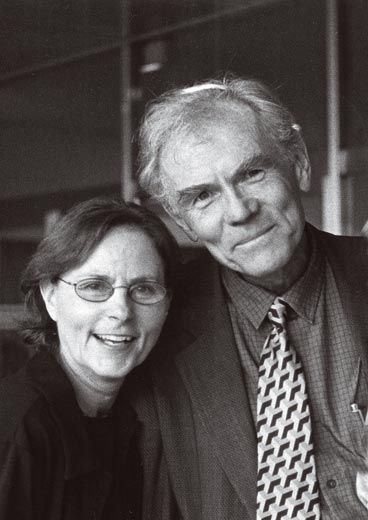

Married, With Camera

Portraitist Emmet Gowin’s most enduring subject is his wife

He wasn't like the other Danville boys, Edith recalls. He looked sharp that night in 1961, clad entirely in black for the dance at the Y; later, she learned that he listened to jazz and classical music. Emmet Gowin wanted to be an artist but was having trouble finding a subject. In Edith Morris, he did. They married three years later, and Gowin went on to make his first photographs of Edith and her extended family.

It was a welcoming family, and a large one, clustered in five houses on a Danville, Virginia, cul-de-sac. By 1971, when this picture was taken, Edith and Emmet had the first of their two sons, Elijah (playing with a train set), and five nephews and nieces (one of whom appears in a blur near the train tracks). Each year, gifts for nearly 20 people would be piled at the foot of a Christmas tree, a young cedar that Emmet would cut from the nearby woods. By mid-morning, the living room floor would be a wasteland of torn wrapping paper. "It would pretty much look like that every Christmas," Edith remembers.

Neither Edith nor Emmet can recall the precise circumstances that led to this photograph, but they know the process well. "She'll look at me and see the way I'm looking at her, and she'll know," he says. "I don't even say anything, I just get up and go get the camera."

"What he'll do is just stare a little bit," she says, "and I know to keep the feeling I have there, whether it's a solemnness or whether it's a glee in my eye—whatever it is, to not get into another mood."

Other photographers have taken their spouses as subjects. Gowin's mentor at the Rhode Island School of Design, Harry Callahan, made abstract pictures of his wife, Eleanor; Alfred Stieglitz said the countless pictures he took of Georgia O'Keeffe formed a single portrait. But Gowin's pictures—with Edith's characteristically defiant, tomboyish air, often tempered by an ethereal light—are anything but derivative. The couple's collaboration launched a distinguished career: Gowin's family photographs earned him fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, and his work has been published in three monographs and featured in numerous museum collections. For the past 34 years, he has taught at Princeton University.

For many years Gowin was content to take pictures mostly of Edith and her family, but that began to change in the early '70s, with the deaths of Edith's grandmother and two of her uncles. With three of his most beloved in-laws gone, Gowin felt diminished.

When he returned to visit with Edith's family for Christmas in 1973, he saw that some of the children had built a treehouse in the yard. "I just out of curiosity climbed up," he says. "One plank had fallen out, and right in that spot there was a marvelous view, about 12 or 15 feet off the ground." He wedged his camera through the gap and took the only picture possible. It turned out to be a beautiful image, framed by snow-covered branches, looking out at the home of Edith's deceased grandmother. He remembers feeling that "just getting up to a high place changed and liberated your vision."

That picture became the bridge between Gowin's early work and the sort of photography that has absorbed him for the past few decades. Since 1980, he has devoted himself largely to aerial landscapes—strip mining in the Czech Republic, farm fields in Kansas, apartment complexes in Jerusalem. These photographs, without a human being in sight, might seem a radical departure, but Gowin says no, they are "records of human action." He is not interested in photographing pristine wildernesses, he adds, but in "tracing out all the lines humans have etched" in the land.

And though Gowin's focus has shifted, he has never stopped photographing Edith, who is now 64, nor does he intend to. "I wanted to pay attention to the body and personality that had agreed out of love to reveal itself," Gowin wrote in 1976. Now, at age 65, he says, "My life as an artist follows so closely my meeting Edith and my love for her that I can think of no way of seeing these two separately."

Former Smithsonian intern David Zax is a writing fellow at Moment magazine.

Books

Emmet Gowin: Photographs, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1990 (out of print)

Emmet Gowin: Changing the Earth, Aerial Photographs by Jock Reynolds, Yale University Art Gallery, 2002

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)