There Was the Magazine Quiz. Then Came the Internet. What Now?

From the “Cosmo Quiz” to Quizilla to Buzzfeed… what’s next?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/58/79589817-f7dc-40ab-a9b0-62d8d178bfb1/istock-157774052.jpg)

In what feels like a Red Wedding that just keeps going, already more than 2,200 people in media have lost their jobs this year in a devastating string of layoffs and buyouts. Fifteen percent of Buzzfeed’s staff was part of that carnage, the decision gutting entire verticals, from the national security team to the LGBT section to the health desk. Among those let go was the company’s director of quizzes, Matthew Perpetua.

Quizzes have long been Buzzfeed’s bread and butter, shaped under former managing editor Summer Anne Burton, who was also among the recent layoffs. The site has four standard types, today, including trivia, poll and checklist, but when people talk about a Buzzfeed Quiz, they’re most likely thinking about the classic: the personality quiz, the one where you select from five different kinds of fruits to find out what private island you’re destined to spend your golden years. Or something like that.

They're fun, sometimes revelatory, an easy conversation starter. But as Perpetua explained in a philosophical postmortem on his personal blog that, unsurprisingly considering his skillsets, went viral, getting rid of his position made a cold kind of economic sense:

“You might be wondering – wait, why would they lay you off? You were doing the quizzes, and that brings in a lot of money! Well, that is true,” he wrote. “But another thing that is true is that a LOT of the site’s overall traffic comes from quizzes and a VERY large portion of that traffic comes from a constant flow of amateur quizzes made by community users.”

As he noted, a student in Michigan who authored dozens of quizzes a week was one of the top traffic drivers to the site. Like all community members, she was not paid for her effort. In a subsequent interview with New York magazine, the quizmaster, Rachel McMahon, a 19-year-old pursuing a communications degree, said that she had previously viewed quizmaking as a hobby, but now felt blindsided by what was going on behind the scenes.

The story feels like an inflection point for the internet quiz. It’s a well-loved genre and an undeniable traffic-driver that’s come a long way from its roots in women’s glossy magazines, yet its worth is not valued accordingly.

The word “quiz” came into the lexicon relatively late in the game, some 250 years ago, when a manager at a Dublin theater used it in a bet that he could get everyone nearby to talk about a nonsense word. While a version of the anecdote may have actually occurred—others substitute quiz with the word quoz and set the scene in London—the veracity of the tale is something of a moot point because before the supposed bet even occurred, the word quiz was already starting to crop up, possibly originating in schoolboy slang to describe a person of ridicule.

The rise of quiz to mean “to question or interrogate,” came later, around the mid-19th century, according to the Oxford Dictionary, which places its origin in North America, where it began to “stand for a short oral or written examination given by a teacher.”

An American educator, physcologist and philosopher named William James is credited with helping establish that modern identity, lexicographers cite a letter he wrote in 1867 about how “giving quizzes in anatomy and psychology” might help students learn better.

By the early 20th century, “quiz” was appearing across media formats. A look through the New York Times’ archive reveals that a “quiz” appeared in the paper as early as 1912 the paper (it was a test on Charles Darwin enclosed in a letter to the editor that asked: “Will any of your readers care to look at the list of questions and see how many they can answer offhand). In the mid-1930s, radio took to the genre, and television following suit, producing early game shows like “The $64,000 Question” and “21.”

But it was the women’s magazine that best laid the groundwork for what was to come online, tapping into the potential of the genre as a way to reveal something about who you were and where you stood in the world.

"Everybody wants to know where they stand," said social psychologist Debbie Then, an expert in women’s magazines, in an interview on the subject. “‘Am I doing this right? Am I doing that wrong? What do I need to do better?’ People want to know how they stack up to other people. They want to compare themselves in a confidential way.”

In turn, the proto-Buzzfeed pop psych quizzes owed a debt to the Proust Questionnaire, a turn-of-the-century parlor game that delved into the psyche of the answer-giver through open-ended questions like “What is your idea of perfect happiness?”, author Evan Kindley chronicles in Questionnaire, which chronicles the history of “the form as form.”

Cosmopolitan magazine didn’t create the women’s quiz—over at Slate, historian Rebecca Onion reports on an early 1950s magazine marketed to young women that was already asking its audience: “What Are You Best Fitted For: Love or a Career?—but it established itself as the gold standard of the genre.

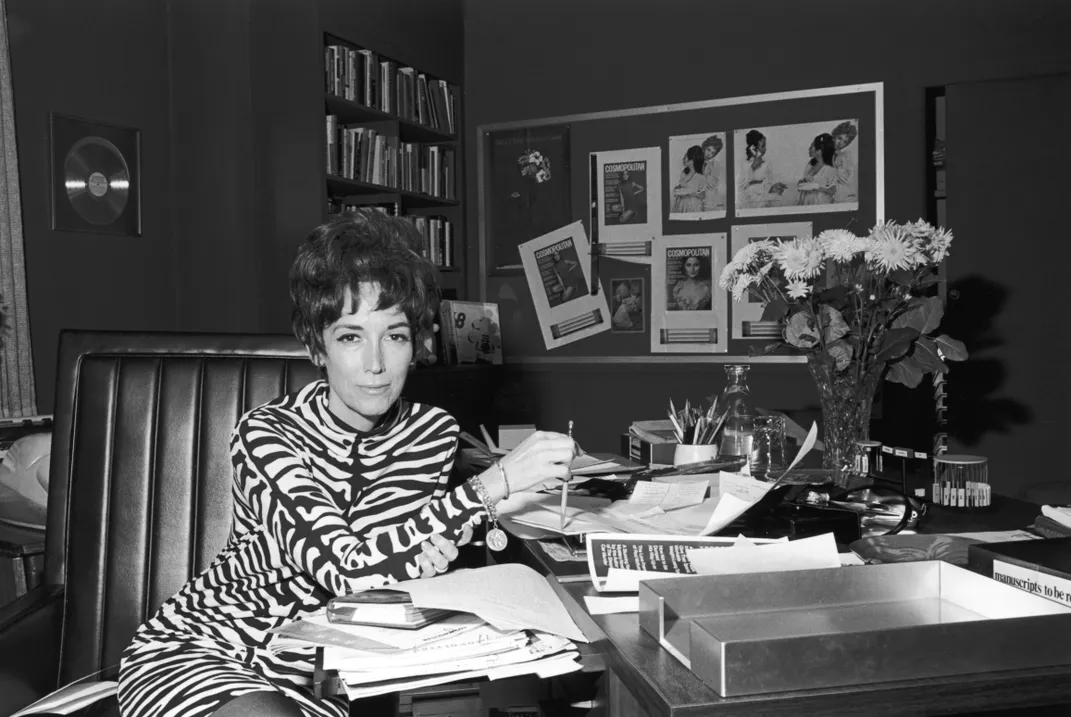

The Cosmo Quiz arrived quickly after writer Helen Gurley Brown, author of Sex and the Single Girl, was named editor in chief of the magazine in 1965, promising a reign of “fun, fearless, female content.” By the summer of ’66, according to Kindley, the earliest incarnation of the quiz, “How Well Do You Know Yourself?,” appeared, the topic seeming to pull directly out of the Proust Questionnaire playbook.

Unlike the Proust Questionnaire, which wasn’t written by the French philosopher but is instead named after him for the timeless answers he provided, the Cosmo Quiz included its own answers to its questions. To do so, Cosmo writers began consulting with subject-matter experts to fill in the questions and weighted answers. (Ernest Dichter, a Viennese psychologist, was consulted for that first go.) Readers, most of whom identified as women, loved the format, perhaps gravitating to the same self-diagnosing psychology well that was turning the advice column into an industry in the U.S.

Often, the theme of the Cosmo Quiz centered around a woman’s desire. Though that topic is rich with nuance, as done through the commodifying lens of the women’s magazine industry, which, as Kindley points out was “designed primarily for commercial rather than political purposes,” the quizzes instead often reinforced a one-size fits all version of the world that even while often salacious, still hewed straight, white and middle class.

In a case study published in the journal Discourse & Society, applied linguistic experts Ana Cristina Ostermann and Deborah Keller-Cohen explain that intentionally or not, across the industry in the 1990s, these sorts of quizzes, which ranged from “personality, and the 'perfect match', to fashion and even the ideal perfume” were still armed with a “heterosexist agenda" which was aimed to teach young people "how to behave,” reinforced by questions and answers to seemingly harmless quiz topics like “What Kind of Flirt Are You?” (published in Seventeen magazine, August 1994).

The early web changed that somewhat with quiz-sharing platforms that anyone could access. For instance, Quizilla, which began in 2002 as site to create and share quizzes, ultimately became a space for all kinds of user-generated content, from poems to journals to stories. While its content certainly mirrored the problems of the quizzes appearing in Cosmo and its ilk, the community format also opened the door for a younger and more diverse bunch of quizmakers, who were often writing for fun to entertain themselves and age-group peers.

That early aughts quiz had the taste of a counterculture zine in some ways. Creators of those DIY publications, which boomed in the 1980s, had long been exploring issues ignored by the mainstream magazine, with topics ranging from body image to politics. Researchers Barbara J. Guzzetti and Margaret Gamboa of Arizona State University chronicled the genre for Reading Research Quarterly in 2004, finding them to be “influential tools for expression by adolescent girls.”

Likewise, when Viacom bought Quizilla in 2006, the talking points in the press boasted the site had become “one of the five top online destinations for teenage girls.”

Buzzfeed launched that same year, and would go on to dominate the market. The Buzzfeed Quiz didn’t happen overnight, as Burton explained in a 2014 interview with the Huffington Post. Instead, she pointed to a combination of factors that led to the rise of genre, crediting staff writer and illustrator Jen Lewis, for instance, with designing the instantly recognizable square format. The early Buzzfeed quizmakers, which included Perpetua, then a senior music writer, found niche, specific content that made the quizzes pop. While the company hadn’t yet opened the quizzes up to community members, it was soon to come, followed by sponsored quizzes, all of this contributing to Buzzfeed’s $300 million in revenue last year.

Yet for all its value, the internet quiz still struggles for legitimacy that it has long earned.

The superficiality of it all is easy to mock—trending now on Buzzfeed: “Pick Your Favorite Desserts And We’ll Guess Your Age With 100% Accuracy,” “Which Periodic Element Are You Based On Your Random Preferences,” and “Eat At Pop’s And We’ll Tell You Which ‘Riverdale” Character Is Your New Bestie”—but a great quiz doesn’t need to be Hemingway to feel like a work of art.

In a separate interview with Slate, Rachel McMahon talked about how much she loved to create quizzes and see others enjoy her work. Like many, she wasn’t sure where to go from here.

“I think BuzzFeed would probably laugh in my face if I asked for money, knowing they have all these other community contributors to lean on. Although I’m their biggest community contributor, I’m just one piece,” she said.