The Fantastic Mr. Dahl

The British author’s world—antic, subversive, wildly inventive and monstrously humane—returns to the screen in Steven Spielberg’s The BFG

:focal(530x592:531x593)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/d3/55d36fb8-0683-454c-957c-242239f2b782/julaug2016_c08_roalddahl-wr-v1.jpg)

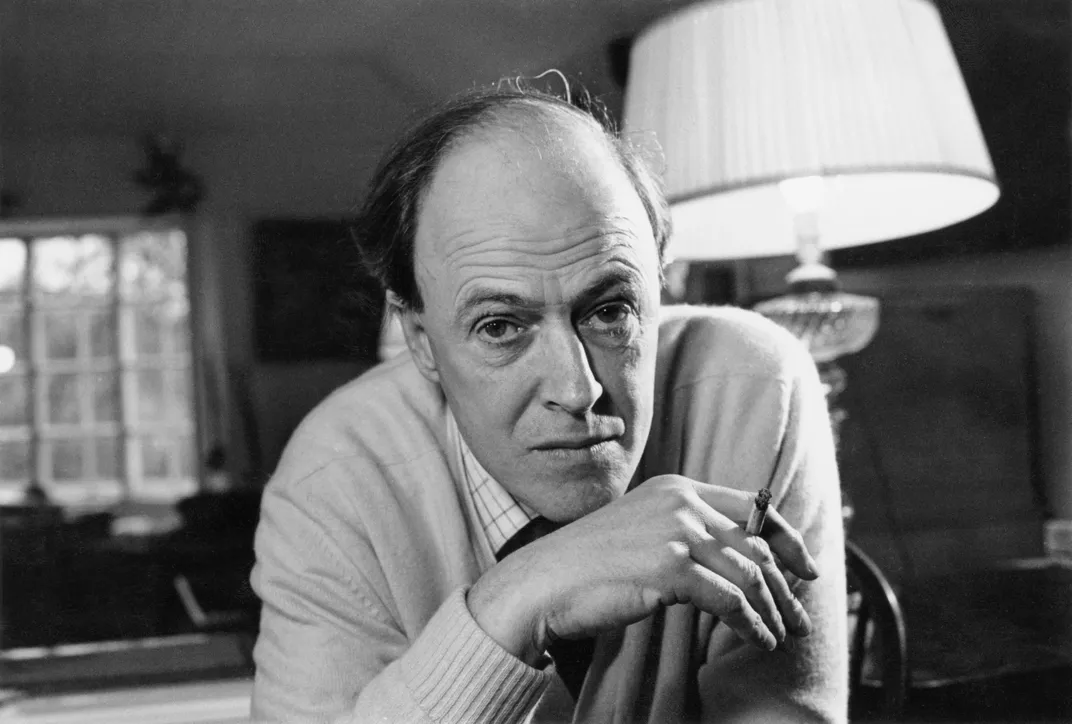

The garden shed. Different people know different things about Roald Dahl. You may recall his short story about a woman who clubs her husband to death with a leg of lamb and disguises the murder weapon by roasting it; or his marriage to Hollywood star Patricia Neal and the agonies that slowly destroyed it; or the first of his best-selling children’s books, James and the Giant Peach, or the richer, fuller later ones written during his second, happy marriage, such as The BFG, a tale about a big friendly giant, adapted into the new Disney film directed by Steven Spielberg. And then there are the stories of his boasting, his bullying, his orneriness, his anti-Semitism, balanced over time by acts of kindness and charity, and by the posthumous work of a foundation in his name.

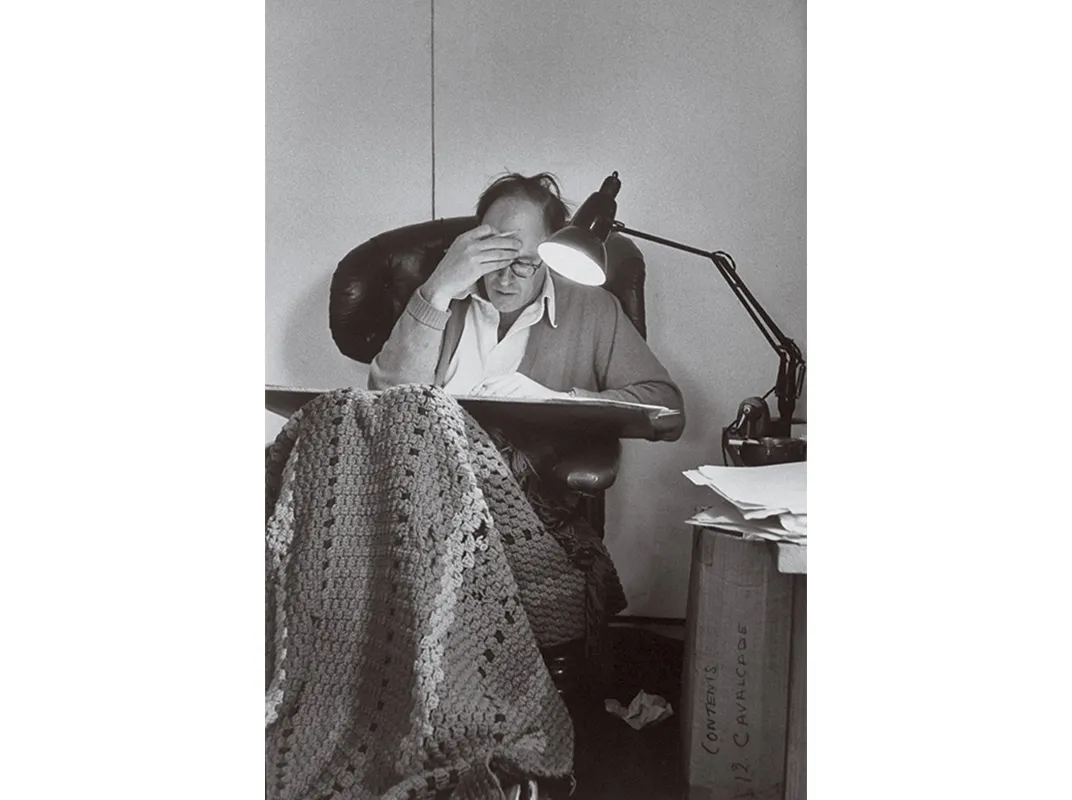

Almost everyone, though, knows about the shed. It has appeared in hundreds of articles and documentaries about him and is a centerpiece of the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. The shed was, Dahl said not wholly originally, a kind of womb: “It’s small and tight and dark and the curtains are always drawn...you go up here and you disappear and get lost.” Here, at the top of his garden, hunched in an old winged armchair, in a sleeping bag when it was cold, his feet on a box, a wooden writing board covered in green billiard cloth balanced across the chair arms; here, surrounded by personal relics, totems, fetishes (his father’s silver paper knife, a heavy ball made out of the wrappings of chocolate bars when he was a clerk at Shell Oil, bits of bone from his much-operated-on spine, a cuneiform tablet picked up in Babylon during World War II, a picture of his first child, Olivia, who died when she was 7; a poster for Wolper Pictures, makers of the first Willy Wonka film, naming the company’s star authors: DAHL, NABOKOV, PLIMPTON, SCHLESINGER, STYRON, UPDIKE)—here was where he worked.

Like painters with their studios, many writers have had versions of a garden shed. Dahl’s was more than usually private, scruffy, obsessional, but why is it so memorable? To be sure, along with his height and his war service as a fighter pilot and his superstitious insistence on Dixon Ticonderoga yellow pencils, it has become—already was in his lifetime—part of the Roald Dahl brand. It’s so much a trademark, in fact, that it’s sometimes misremembered as a remote lakeside cabin like Thoreau’s, as a tower like Montaigne’s or W. B. Yeats’, as a gipsy caravan such as the one where the boy narrator and his quirky single-parent father live in one of Dahl’s best-loved stories, Danny the Champion of the World: “a real old gipsy wagon with big wheels and fine patterns painted all over it in yellow and red and blue.” His own children actually had such a caravan in another corner of the same garden at what’s still one of the family homes, Gipsy House, on the edge of Great Missenden, a village in a valley in the Chiltern Hills, west of London.

Yet there’s a halo effect in all this that goes beyond image management, skillful though that has been, especially since his death in 1990. It’s partly to do with austerity nostalgia, which in Britain is linked to the Blitz spirit and rationing, but also to more class-bound cults like those of country houses, boarding schools and other habitats of “not complaining.” In some ways, it’s a northern European thing, not uniquely British: Dahl’s origins were Norwegian.

His father emigrated to the coal-boom port of Cardiff, Wales, in the 1880s and made a modest fortune provisioning cargo ships there. Widowed in 1907, he found a second Norwegian wife; Roald was the third child and only son of this marriage. With the death of the eldest, at age 7, and of their father soon afterward, Roald became the family’s pet (his nickname was “The Apple”) and in his own eyes its protector. Much later, the American writer Martha Gellhorn, who dated him on the rebound from her marriage to Ernest Hemingway, remembered him as living among “a thousand sisters” and “a suffocating atmosphere of adoration.”

The children were given a conventional English boarding-school education, spending their holidays in a comfortable house in the English country town to which their widowed mother had moved, and where she spent the rest of her life: “A young Norwegian in a foreign land,” he wrote in his memoir for children, Boy, “she refused to take the easy way out.” All her children remained close by. Cardiff has enterprisingly named a public space outside the Senedd, seat of the semi-independent Welsh National Assembly, after Roald Dahl, and is making a lot of his centenary, this year. In truth, though, his allegiances were to tough, cold Norway with its grass-topped wooden houses and its uncompromising mythology of giants, dwarfs and Valkyries; and, equally, to an England of scruffy villages, horrible schools and small-time crooks.

Good at sports, very tall, independent, not particularly bright academically but arrogant and somewhat isolated by that, the boy went straight from boarding school into the oil industry and soon found himself in colonial East Africa on what turned out to be the brink of World War II. He enlisted in the Royal Air Force and with next to no training was sent as a fighter pilot to take part in Churchill’s quixotic defense of Greece. If any real-life adventure could outmatch the battle of Dahl’s Big Friendly Giant against the even bigger and far from friendly giants of his children’s story, it’s that of the weeks the 25-year-old spent hurtling through the sky fighting the Luftwaffe and its allies above Athens and, immediately after that, at Haifa, in what was then British-ruled Palestine. The wartime Royal Air Force prided itself on a laconic modesty that in those days was still aspired to by the English in general, but self-effacement was one bit of Englishness Dahl didn’t do. His official combat reports are full of braggadocio: “I followed [the enemy aircraft, a Vichy French Potez] for approx. 3 minutes after the others had broken off and left it with Port engine smoking and probably stopped. Rear gunner ceased fire....It is very unlikely that this Potez got home.” Invalided out of action with back problems caused by an accident (he later claimed, and seems to have come to believe, that he was shot down), the loquacious flying officer was sent to boast for Britain in newly belligerent Washington.

America turned Dahl into a writer, and also into a star. Based in an embassy so glittering that the rising young Oxford political philosopher Isaiah Berlin was a mere staffer there, the handsome war hero talked up his country but above all himself, did a little secret intelligence work while keeping it anything but secret, and wrote stories about the RAF that attracted the Disney brothers’ attention. A fable about the Battle of Britain, The Gremlins, went into development as an animated film, but did not make it to the screen.(Disney adapted the text and pictures into a children’s book, Dahl’s first.) The venture brought trips to Hollywood that, according to one of his children, permanently turned his head. He claimed Clare Boothe Luce and the Standard Oil heiress Millicent Rogers among his conquests, and began a lasting relationship with Tyrone Power’s French wife, Annabella (Suzanne Charpentier).

Like many of those brought to prominence by the war, Dahl found the immediate post-1945 years difficult. Soon, though, Collier’s magazine and the New Yorker were drawn to a new, terse, comic-vengeful element in his fiction, and the short stories later famous as Tales of the Unexpected began to appear. He got to know Lillian Hellman and through her met Pat Neal, then still involved with Gary Cooper.

The tragic story of their marriage—their son permanently injured in a traffic accident in Manhattan; a young daughter dead of measles in the rural haven to which they retreated; Pat’s own disabling strokes when she was only 40, newly pregnant and at the height of her fame—all this, along with Dahl’s own successes in Neal’s world (he’s credited with the scripts of You Only Live Twice and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang), has been told in articles, books and a movie, The Patricia Neal Story. Familiar, too, from obsequious journalists and, now, from the museum that commemorates him, is the narrative of his self-transformation into one of the leading writers of his day, of any day, or so he seemed to think. When U.S. publishers altered his spelling, he demanded grandly: “Do they Americanize the Christmas Carol, or Jane Austen?” This was in a letter to Robert Gott-lieb, then editor in chief at Knopf, later editor of the New Yorker, and one of a handful of American publishers who played substantial roles in shaping Dahl’s books—like Max Perkins with Scott Fitzgerald, Dahl observed—while putting up with his increasingly overbearing behavior. (Another Random House editor, Fabio Coen, radically reworked the plot for Fantastic Mr Fox.)

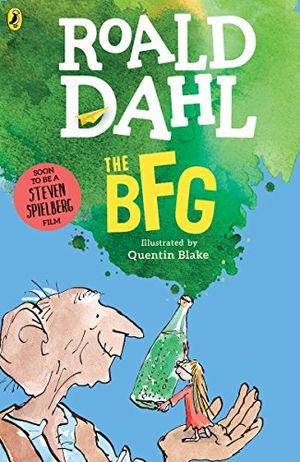

Or not putting up with it. Gottlieb eventually fired Dahl, telling him that his abusiveness and bullying had made “the entire experience of publishing you unappealing for all of us.” Dahl’s British publisher then offered The BFG to Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which would also come out with The Witches, Boy and Going Solo.

In all this Dahl and his family became rich, especially through films based on his books—projects that he made a point of despising (he called The Witches, with Anjelica Huston, a “stupid horror film” and told everyone not to go). The originally modest but frequently expanded white, four-square house he bought with Pat Neal in the 1950s grew opulent inside, well-furnished with the help of his younger, second wife, Felicity.

A stylist and designer, Felicity gave Dahl an Iberian-Catholic feeling for baroque that complemented his taste for modernism. As a collector and part-time dealer, he had done well in the loose 1940s art market—Matisse drawings, Picasso lithographs, Rouault watercolors—with a particular enthusiasm for the English colorist Matthew Smith, whom he befriended. The garden that he planned and worked in has handsomely matured, so that the house is now hidden by trees and shrubs. The writing hut, though, was a throwback, a small shrine to tougher times: to the Norwegian wood houses of his parents’ late 19th-century childhoods, and to the cramped cockpit of the Hawker Hurricanes into which the 6-foot-5 RAF pilot had crunched himself.

Now, front wall removed, the hut sits in a museum behind a glass screen, though nearby there’s a user-friendly replica of an old chair of Dahl’s where you can sit, put his green-felt board across the arms and photograph yourself writing.

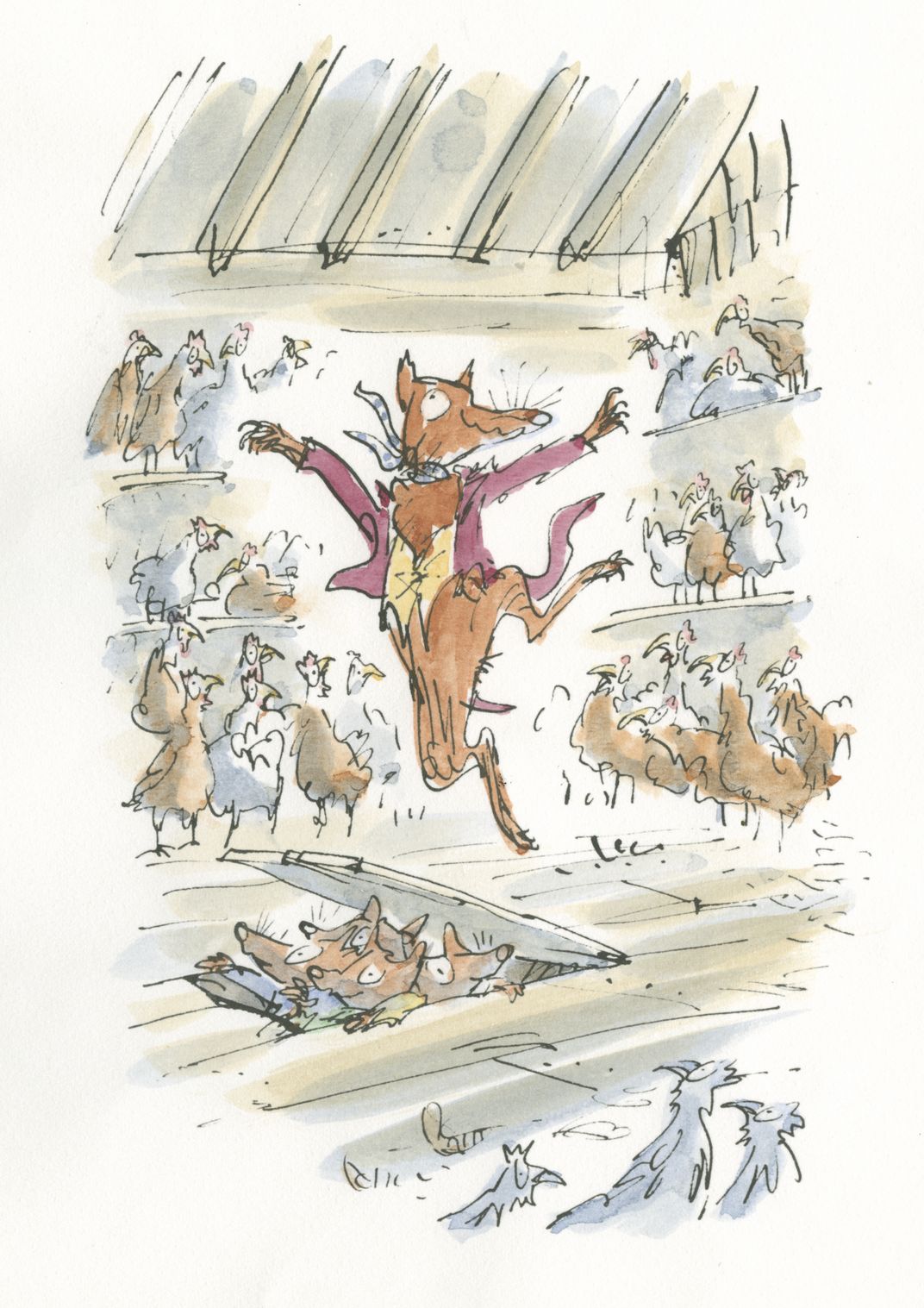

Ascetic yet secure, the hermitage-shed and other aspects of Dahl’s imaginative world mingle in the tale of a creative Neanderthal, the Big Friendly Giant, now reimagined by Steven Spielberg. Bullied by his still bigger neighbors (how many of Dahl’s books involve bullying!), the relatively little big man retreats to a cave of his own where he mixes dreams that, like a butterfly collector, he has caught in a long net, turning them into happier creations to be blown into the minds of sleeping humans. “You can’t collect a dream,” the BFG is told by little Sophie (named for Dahl’s now independently famous granddaughter, the writer and former fashion model). He is impatient with Sophie’s lack of understanding but more so with his own incoherence—his malapropisms, his spoonerisms, modeled in part on Pat Neal’s gratuitously beautiful speech muddles after her brain hemorrhage. Yet the giant also has a special gift. “A dream,” he tells Sophie, “as it goes whiffling through the night air, is making a...buzzy-hum so silvery soft, it is impossible for a human bean to be hearing it,” but with his huge ears, he can capture “all the secret whisperings of the world.” You don’t have to be a dreamer to see this as idealized autobiography. The BFG is himself both a reader and a would-be writer. Among the authors he most admires is the one he calls Dahl’s Chickens.

Dahl’s softness for hardship—the rigors of the shed, the ways in which his stories redeploy well-worn Victorian scenarios of poverty, orphanhood, brutal schooling—was connected to his belief in village values. Gipsy House is up a track at the northern end of Great Missenden. Below it, on the other side of the old London road, runs a stream, the Misbourne, and, beyond that, the parish church where Dahl is buried. The house was close to where his mother and sisters lived (Pat and Roald’s daughter Tessa called the neighborhood “The Valley of the Dahls”). The writer walked in the Chiltern beech woods, drank in the village pubs, employed local workmen, listened to their stories and used elements of all this in his fiction.

Living in a country village is a way of preserving something of a past that’s itself inevitably a bit fictional, given that villages didn’t always (for example) have cars and phones. Children’s stories can be another kind of preservative, for writer as well as readers. If the houses outside the window are bent and crooked, as they are in The BFG, and the shop across the street sells buttons and wool and bits of elastic, and tall, alarming but kindly men wear collarless shirts, you know where you are, as the English like to say. Though where exactly that is, what with novels, films and the growth of Dahl’s reputation, as well as the sheer passage of time, has become a complicated question.

**********

The BFG begins at a version of No. 70 High Street, Great Missenden, a harmless, picturesque timbered house, but in Dahl’s story a cruel orphanage. From an upper window the Big Friendly Giant snatches Sophie. (Spielberg’s version moves the shocking opening scene to London.) Today, on the other side of the narrow street from this building and from Red Pump Garage—no longer a petrol station, though the pumps have been preserved in homage to Danny the Champion of the World, in which they figure—if you go through the archway of an ancient former coaching inn you come up against the gates of Mr. Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. Actually, they’re a smaller-scale replica of the ones used in the 2005 Warner Bros. movie. You are about to enter the Dahl museum, simultaneously a biographical display, a playground, a celebration of and stimulus to reading and writing, and an unpretentious, cheerful kind of shrine.

It’s one of a handful of such places that have sprung up in Britain, though they tend to be in writers’ birthplaces more often than where they actually wrote. Charles Dodgson was born in a village in Cheshire, where, not long before last year’s 150th anniversary of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a museum was set up in his memory, though there’s not much in Lewis Carroll’s writing you can connect with the region. (Cheshire cats were known before he made them famous.) Peter Pan has more to do with London’s Kensington Gardens than with Kirriemuir, the Scottish town north of Dundee of his author, J. M. Barrie, whose birthplace is now open to visitors. Birmingham’s newly restored Sarehole Mill, where J.R.R. Tolkien played as a boy, has become a center of pilgrimage for Middle-earth questers, but its pizza-making demonstrations and conference facilities would not have appealed to the writer.

The well-thought-out Dahl museum, by contrast, belongs exactly where it is, in the middle of the village the author loved, and within walking distance of his home.

Gipsy House itself is unobtrusively well protected, and not just by trees. A free map available at the museum suggesting Dahl-related walks around Great Missenden doesn’t show its whereabouts. In general the Dahls, while not all exactly publicity shy, have made a much better job of protecting their private lives and, especially, the reputation of Roald Dahl than he did himself. Spielberg’s executive producer, Kathleen Kennedy, worked closely with the literary estate, and the director himself gave family members a tour of the set during filming in Vancouver. But while a request for an interview with Felicity Dahl for this article was welcomed, it was simultaneously fended off with forbidding conditions, among them that the “interviewees would want copy approval of the finished piece, including but not restricted to direct quotes.”

It seems relevant that Dahl was a collector—of paintings, wine, varieties of flowers and budgerigars, as well as more personal talismans—because the flip side of collecting is rejecting. Invited to take part in a local version of a British TV show about antiques, “Going for a Song,” in which panelists identified and valued objects brought by the audience, he dismissed most of what he was shown as “total crap.” Similarly, much of the energy in his stories can seem harshly misanthropic. I had an opportunity to speak with Spielberg about this, among other things, between near-completion of The BFG in April (“It’s very, very close to the wire”) and its May premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. He made the point that in the past, children’s stories were less protective, more willing to expose the young to unpleasantness, indeed horror: “children being attracted by what scares them, and having to suffer nightmares through their formative years.” He instanced the dark tales collected by the Brothers Grimm and suggested that Disney drew on but softened the tradition. “The darkness in Bambi is no more or less than the darkness in Fantasia or Dumbo or Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but Disney knew how to balance light and dark, he was great at it even before George Lucas conceived of the Force!” For Disney and, he implied, for Dahl, “There could be healing. There could be fear and then there could be redemption.”

Context is important, of course: When children first encounter the world’s dark side, they need the presence of adults to reassure them. Spielberg himself read James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to his seven children, he told me, and now reads to his grandchildren. “Reading aloud is, you know, sort of what I do best. I probably get more value hearing a story that I’m reading to my children and grandchildren but am also reading to myself—I’m in the room, both the reader and the audience. It gives you an interesting double-mirror effect.”

Still, some of Dahl’s work is harsh by any standards: The Twits, in particular, with its mutual destructiveness between a bearded old man—“Things cling to hairs, especially food....If you looked closer (hold your noses, ladies and gentlemen)...”—and his ill-favored wife (“Dirty old hags like her always have itchy tummies...”), plays to readers’ nastiest responses.

And there was Dahl’s notorious proneness to anti-Semitic remarks, recently downplayed by Spielberg when asked about it by reporters at Cannes. Dahl’s defenders insist that the man they knew was reflexively provocative and would express views he did not hold to cause a reaction. In my biography of Dahl, however, I quote a letter he wrote to an American friend, Charles Marsh, full of savagely violent “jokes” about Jews and Zionism, prompted by a request for support he had received while helping to run a charitable foundation of Marsh’s. The appeal had come from the Stepney Jewish Girls’ Club and Settlement in East London. This was in 1947, between the Nuremberg Trials and the founding of the state of Israel, and it goes way beyond the casual anti-Semitism common among certain kinds of English (and Americans) at the time.

Yet what lives on equally truthfully in today’s memory of Dahl is the generous, hospitable, inclusive man who invited his jobbing builder in to play billiards with his famous guests, and who sought out and encouraged any glimmer of originality in anyone he liked: a support system that lives on. The shed he wrote in is surrounded by other stimuli to story-making. There are books to take down and read, dictionaries, pencils and paper, videos of living writers talking about how they learned their trade and giving advice (“Read read and read”). One area is full of words and of vivid, potentially jokey phrases on wood blocks (“superstar,” “the ghastly,” “the toilet,” “stumbled into”), which you can arrange in any order. The buildings also house Dahl’s archive, and bits of his manuscripts are on display, pictures of people he turned into characters.

An older shrine, also connected with Dahl, lies farther along the London road, in the next village, Little Missenden. The church, some of which dates back to before 1066, is fabulous in its medieval muddle, and the writer loved it not least for an ancient wall painting that faces you as you go through the 14th-century doorway. It depicts St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers, as a scrawny giant carrying a diminutive figure on his shoulder, like an early, religious version of the BFG. Though the heroine of Dahl’s story is named Sophie, the book is dedicated to his eldest child, Olivia. She died in 1962 of measles encephalitis, at age 7, and is buried in the churchyard. Dahl visited her grave obsessively in the following months, filling the site with rare alpine plants and, for once, was deprived of exaggeration: “Pat and I are finding it rather hard going,” he wrote to his then friend and publisher, Alfred Knopf. His earliest stories, among them “Katina,” about a war-orphaned Greek girl adopted by an RAF squadron, already showed a marked tenderness toward children. The vulnerability may have had one of its sources in the death of his elder sister Astri when he was 4.

In any case it was painfully deepened, later, by what happened to Olivia and, a couple of years before that, to his baby son, Theo, his skull fractured in multiple places when his pram was crushed between a Manhattan taxi and a bus. Ultimately, Theo survived and recovered more substantially than had been expected, although some of the damage was permanent.

Dahl’s first successful book for children, James and the Giant Peach, came soon after Theo’s accident; the second, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, after Olivia’s death. By the mid-1960s, despite all the efforts Pat Neal made after the stroke, he was in practice the single parent of four young children: Tessa, Theo, Ophelia and Lucy. Later, how he saw himself at this time emerges in romanticized form in Danny, written when the marriage was still just about holding together but he had already begun a relationship with Felicity d’Abreu. She brought him happiness and also a degree of emotional steadiness and protection that, though it didn’t prevent some startling outbursts, made possible his kinder, longer books of the 1980s: The BFG, The Witches and Matilda. Something of the change he went through was symbolized by what became a family ritual. After telling early versions of The BFG to his younger daughters at bedtime, he would climb up a ladder outside their bedroom window and stir the curtains for added effect.

His somewhat belated growth into emotional adulthood affected the construction of his stories, in turn helped by some hard-working editors. Matilda, in the version of the character we know through the 1988 book or the long-running, record-breaking musical first staged at Shakespeare’s Stratford in 2010, is a “sensitive and brilliant” girl, ill-treated by her gross parents. In the original typescript she’s a little monster, constitutionally misbehaved and prone to using her magical powers to nobble, or rig, horse races. Matilda “was born wicked and she stayed wicked no matter how hard her parents tried to make her good. She was without any doubt the most wicked child in the world”—an off-shoot from the unforgiving Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, written a quarter of a century earlier. The new tone was already there in The BFG, a book that harmonizes the best in Dahl’s writing.

At first sight it might seem a strange story for Spielberg to have taken on. Or anyone, really, in this anxious world. A gigantic, scruffy old man appears by night at a young girl’s bedroom window and carries her away to a dark cave full of sinister equipment. Even worse versions of Sophie’s captor, monsters of whom he himself is afraid, prowl the desert landscape outside.

The giant assures the little girl that he means her no harm, but some of his habits are obnoxious and his talk is confused and racist. He tells Sophie his cannibal neighbors enjoy eating Turks, who have a “glamourly” flavor of turkey, whereas “Greeks from Greece is all tasting greasy.” He himself is a vegetarian, at least until his first experience of a Full English Breakfast, later in the story, but the poor soil of Giant Land yields nothing but what he calls “snozzcombers”: “disgusterous,” “sickable,” “maggotwise” and “foulsome.” The fun of the BFG’s language is well aimed at children, as are the more boisterous aspects of his digestive system. But there’s another aspect of the fantasy that may seem surprising in its patriotic appeal. When the unfriendly giants set off on a child-hunting expedition to England, Sophie persuades the BFG that Queen Elizabeth II, warned by a dream he is to concoct and blow through her bedroom window, will help stop them.

As it happens, the film appears in the year of the queen’s 90th birthday, as well as Dahl’s centenary. She is represented “very honorably,” Spielberg assures me, “except for one little moment in our story that I hope is not too upsetting for the royal family.” (Readers of the book may be able to guess what that comic moment is.)

The creative match between Spielberg and Dahl seems deeply consonant. A co-founder of DreamWorks, the director has often said “I dream for a living.” As for the relationship that develops between Sophie and the BFG, it isn’t far from the one between Elliott and E.T.: an at first frightening outsider and a vulnerable child, each learning from and in different ways dependent on the other. The first thing Spielberg mentioned when I asked what drew him to the book was that the protagonists, despite disparities, eventually “have a relationship completely at eye level.” Never shy of the sentimental, he added, “The story tells us that it’s the size of your heart that really is what matters.” Each artist has a knack for showing the world from a child’s viewpoint while achieving a connection also with adults. And Dahl’s book, Spielberg pointed out, was published in 1982, the year that E.T. appeared, suggesting that there was something fortuitous in this, something in the air that he called “a kismet thing.”

Like E.T., the new film was scripted by the director’s longtime friend Melissa Mathison, who finished it just before her untimely death last year of neuroendocrine cancer. Mathison “related passionately” to the project, Spielberg said. John Williams returned as Spielberg’s composer for a score that the director describes as “like a children’s opera” that “retells the story but in a more emotional way.”

The cast features Mark Rylance (most recently the wry, put-upon Russian agent Rudolf Abel in Bridge of Spies) as the BFG, and Penelope Wilton, transplanted from Downton Abbey (Mrs. Crawley) to Buckingham Palace, as the queen. Sophie is played by 11-year-old Ruby Barnhill in her first film role. The newcomer and the veteran Rylance, says Spielberg, “constantly inspired each other.”

The BFG calls himself “a very mixed up Giant,” and part of the story’s charm and optimism come from Sophie’s helping him, once the bad giants have been vanquished with British military help, “to spell and to write sentences.” Literacy, and children who, for whatever reason, get mixed up acquiring it, increasingly concerned the aging Dahl. The last of his stories, about a tortoise that, in the old-fashioned phrase, is a bit backward, is called Esio Trot. Dahl had realized that good could be done by his books and the wealth they brought him. He was never any good at committees—his involvement in one of British officialdom’s recurrent attempts to reform English teaching ended almost as soon as it began—but in his crotchety, stick-waving fashion he talked a lot of sense, not least about the value of nonsense and of what he called “sparkiness,” its close cousin. After his death, Dahl’s wife, Felicity, who had recently lost a daughter of her own to cancer, founded a charity in his name, devoted to encouraging reading and writing and, beyond that, to helping disabled and seriously ill children, their families and nurses.

Ten percent of Dahl’s global royalties go to Roald Dahl’s Marvellous Children’s Charity, generating the bulk of its annual income of about $1 million. Spielberg is conscious that the release of The BFG will contribute to the charity. Even beyond that immediate effect, he says, it’s crucial to keep in mind the transformative power of Dahl’s tale transmuted into film. “It’s very important,” he says, “that all children are able to be not just entertained, but also that the stories can help them with the challenges in their personal lives.”

As far as Dahl was concerned, this was a two-way process. More and more noticeably in his best work, from “Katina” in 1944 to The BFG, The Witches and Matilda four decades later, adults somehow or other rescue children and, in the process, are somehow or other rescued themselves. His daughter Lucy once told me that during her troubled adolescence, “All I had to do was say ‘Help me’” and her father would sort something out “in an hour.”

As time went on, the former misanthrope discovered, perhaps to his surprise, that his care was reciprocated, and since his death, the process has grown in many ways, direct and indirect. His own foundation apart, his activist daughter Ophelia, for example, co-founded the international humanitarian nonprofit Partners in Health, with physician Paul Farmer.

Dahl himself may not have found, as the BFG and Sophie do, that “There was no end to the gratitude of the world”—but quite a lot of people in the world are grateful to him, all the same.

The BFG