How Denim Became a Political Symbol of the 1960s

The blue jeans fabric conquered pop culture and fortified the civil rights movement

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/4e/084e3c2b-8911-4646-a815-e0a4ef33f504/pro_icon_jeans.jpg)

In the spring of 1965, demonstrators in Camden, Alabama, took to the streets in a series of marches to demand voting rights. Among the demonstrators were “seven or eight out-of-state ministers,” United Press International reported, adding that they wore the “blue denim ‘uniform’ of the civil rights movement over their clerical collars.”

Though most people today don’t associate blue denim with the struggle for black freedom, it played a significant role in the movement. For one thing, the historian Tanisha C. Ford has observed, “The realities of activism,” which could include hours of canvassing in rural areas, made it impractical to organize in one’s “Sunday best.” But denim was also symbolic. Whether in trouser form, overalls or skirts, it not only recalled the work clothes worn by African Americans during slavery and as sharecroppers, but also suggested solidarity with contemporary blue-collar workers and even equality between the sexes, since men and women alike could wear it.

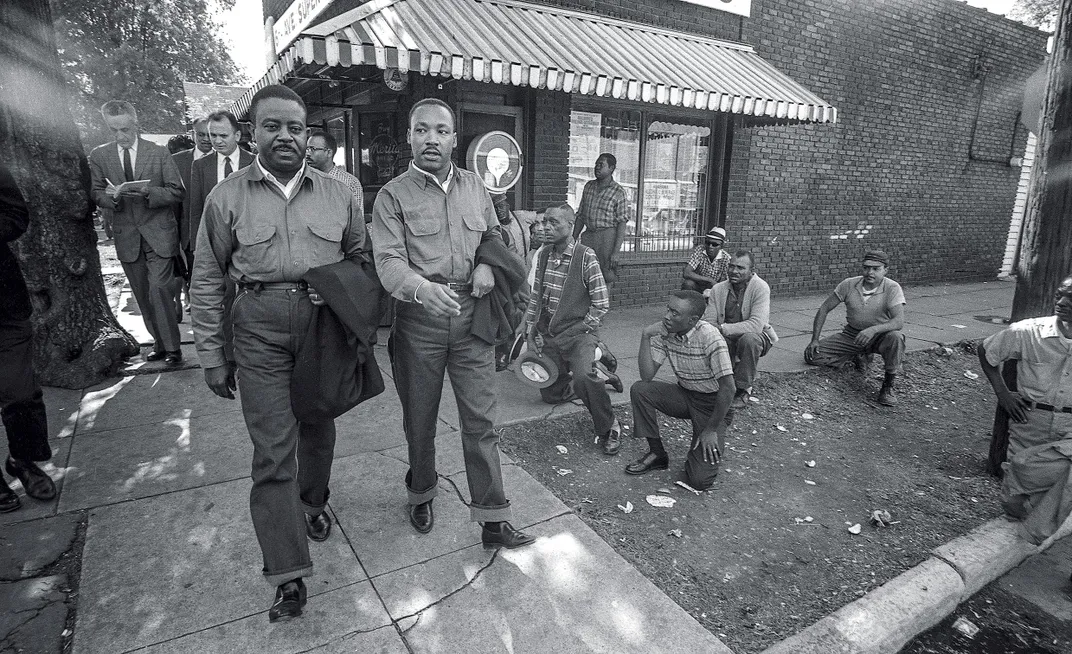

To see how civil rights activists adopted denim, consider the photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy marching to protest segregation in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Notably, they are wearing jeans. In America and beyond, people would embrace jeans to make defiant statements of their own.

Scholars trace denim’s roots to 16th-century Nîmes, in the South of France, and Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Many historians suspect that the word “denim” derives from serge de Nîmes, referring to the tough fabric French mills were producing, and that “jeans” comes from the French word for Genoa (Gênes). In the United States, slaveowners in the 19th century clothed enslaved fieldworkers in these hardy fabrics; in the West, miners and other laborers started wearing jeans after a Nevada tailor named Jacob Davis created pants using duck cloth—a denimlike canvas material—purchased from the San Francisco businessman Levi Strauss. Davis produced some 200 pairs over the next 18 months—some in duck cloth, some in denim—and in 1873, the government granted a patent to Davis and Levi Strauss & Co. for the copper-riveted pants, which they sold in both blue denim and brown duck cloth. By the 1890s, Levi Strauss & Co. had established its most enduring style of pants: Levi’s 501 jeans.

Real-life cowboys wore denim, as did actors who played them, and after World War II denim leapt out of the sagebrush and into the big city, as immortalized in the 1953 film The Wild One. Marlon Brando plays Johnny Strabler, the leader of a troublemaking motorcycle gang, and wears blue jeans along with a black leather jacket and black leather boots. “Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” someone asks. His reply: “Whaddaya got?”

In the 1960s, denim came to symbolize a different kind of rebelliousness. Black activists donned jeans and overalls to show that racial caste and black poverty were problems worth addressing. “It took Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington to make [jeans] popular,” writes the art historian Caroline A. Jones. “It was here that civil rights activists were photographed wearing the poor sharecropper’s blue denim overalls to dramatize how little had been accomplished since Reconstruction.” White civil rights advocates followed. As the fashion writer Zoey Washington observes: “Youth activists, specifically members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, used denim as an equalizer between the sexes and an identifier between social classes.”

But denim has never belonged to just one political persuasion. When the country music star Merle Haggard criticized hippies in his conservative anthem “Okie From Muskogee,” you bet he was often wearing denim. President Ronald Reagan was frequently photographed in denim during visits to his California ranch—the very picture of rugged individualism.

And blue jeans would have to rank high on the list of U.S. cultural exports. In November 1978, Levi Strauss & Co. began selling the first large-scale shipments of jeans behind the Iron Curtain, where the previously hard-to-obtain trousers were markers of status and liberation; East Berliners eagerly lined up to snag them. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, when Levis and other American jean brands became widely available in the USSR, many Soviets were gleeful. “A man hasn’t very much happy minutes in his life, but every happy moment remains in his memory for a long time,” a Moscow teacher named Larisa Popik wrote to Levi Strauss & Co. in 1991. “The buying of Levi’s 501 jeans is one of such moments in my life. I’m 24, but while wearing your jeans I feel myself like a 15-year-old schoolgirl.”

Back in the States, jeans kept pushing the limits. In the early 1990s, TLC, one of the best-selling girl groups of all time, barged into the boys’ club of hip-hop and R&B wearing oversized jeans. These “three little cute girls dressed like boys,” in the words of Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, one of the group’s members, inspired women across the country to mimic the group’s style.

Curiously, jeans have continued to make waves in Eastern Europe. In the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections in Belarus, activists marched to protest what they characterized as a sham vote in support of an autocratic government. After police seized the opposition’s flags at a pre-election rally, one protester tied a denim shirt to a stick, creating a makeshift flag and giving rise to the movement’s eventual name: the “Jeans Revolution.”

The youth organization Zubr urged followers: “Come out in the streets of your cities and towns in jeans! Let’s show that we are many!” The movement didn’t topple the government, but it illustrated that this everyday garment can still be revolutionary.

The Indigo Clash

Why the dye that would put the blue in jeans was banned when it reached the West —Ted Scheinman

It might seem odd to outlaw a pigment, but that’s what European monarchs did in a strangely zealous campaign against indigo. The ancient blue dye, extracted in an elaborate process from the leaves of the bushy legume Indigofera tinctoria, was first shipped to Europe from India and Java in the 16th century.

To many Europeans, using the dye seemed unpleasant. “The fermenting process yielded a putrid stench not unlike that of a decaying body,” James Sullivan notes in his book Jeans. Unlike other dyes, indigo turns cloth vivid blue only after the dyed fabric has been in contact with air for several minutes, a mysterious delay that some found unsettling.

Plus, indigo represented a threat to European textile merchants who had heavily invested in woad, a homegrown source of blue dye. They played on anxieties about the import in a “deliberate smear campaign,” Jenny Balfour-Paul writes in her history of indigo. Weavers were told it would damage their cloth. A Dutch superstition held that any man who touched the plant would become impotent.

Governments got the message. Germany banned “the devil’s dye” (Teufelsfarbe) for more than 100 years beginning in 1577, while England banned it from 1581 to 1660. In France in 1598, King Henry IV favored woad producers by banning the import of indigo, and in 1609 decreed that anyone using the dye would be executed.

Still, the dye’s resistance to running and fading couldn’t be denied, and by the 18th century it was all the rage in Europe. It would be overtaken by synthetic indigo, developed by the German chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer—a discovery so far-reaching it was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905.