Louis Renard, an 18th-century book publisher who moonlighted as a British spy, had a somewhat tenuous relationship with the truth.

As writer and rare-book collector Edward Brooke-Hitching notes in The Madman’s Library: The Strangest Books, Manuscripts and Other Literary Curiosities From History, Renard “knew even less” about Indonesian wildlife than the average European of his day. Far from letting this obstacle stand in his way, however, the publisher leaned into his imagination, producing a fantastical compendium of fish from the opposite of the globe that featured illustrations of a mermaid, a four-legged “Running Fish” that trotted around like a dog and a host of other impossibly vivid-hued creatures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/ac/98ac54d2-a138-40ff-a79f-d012d0f7ee52/louis_renard_krabbe_imperiale_poissonsecrevisirena_0175.jpg)

Renard’s Fishes, Crayfishes, and Crabs (1719) is one of hundreds of unusual titles featured in Brooke-Hitching’s latest book. From books that aren’t actually books—like 20 Slices of American Cheese, a 2018 volume with a name that conveys all one really needs to know—to books made out of flesh and blood to books of spectacular size, The Madman’s Library takes readers on a riveting tour of literary history’s most overlooked corners.

Smithsonian spoke with Brooke-Hitchings to learn more about his ten years of collecting and research that he needed to pull the book together. The author also shared insights on some of his favorite literary curiosities (see below).

You grew up as the son of a rare-book dealer. How did this upbringing influence your career path?

My dad specialized in British travel and exploration—explorers’ journals and such. But really, as a dealer, you get everything coming through your doors. As a kid, initially you’re not very interested in what your parents do. It’s always the strange things about their job that catch your eye, from reading histories of witches to seeing an arrowhead that killed a particularly adventurous explorer—things you don’t need a PhD in the history of the subject to become really intrigued by.

The key was learning that you can find your own way through history. You don’t have to take the established path that probably bored you to death in school. You don’t have to memorize the wives of Henry VIII and so on. You can look for back alleys and things that particularly appeal to you. For me, that term was always “curiosities.”

How do you define literary curiosities?

It’s obviously subjective, but the more experienced you are, the more books you see, the more your radar is sensitive to something that pings with its strangeness. Reaching behind me just for the first books that are in my bag, the first one in my hand is something I found on eBay. It’s called A Peace of My Mind: Poetry by Charlie Sheen, and it’s a self-published collection of just a few copies that [the Hollywood actor] Sheen made and then gave to a few of his friends. It’s just bizarre, and there’s some really strange and terrible poetry in it. One is called “Heretic Proof,” and it ends with the lines “Turtle, android, pain. / Endeavor, endless, end. / P.S. Janonis.” No idea what that means, but isn’t that such an obvious curiosity?

What kinds of books are included in The Madman’s Library?

The problem with collecting instincts is that you have to have a theme, and I realized that actually, these books don’t really share very much other than the fact that they are very, very strange. I love literary hoaxes, being able to hold in your hands a physical lie that was designed to deceive its reader. It’s a lie that you can smell and rifle through the pages of. You’re in on the joke with the author; you’re winking back at them. They’re quite a fun thing to collect, and they’re not expensive because they’re not considered to have much academic significance.

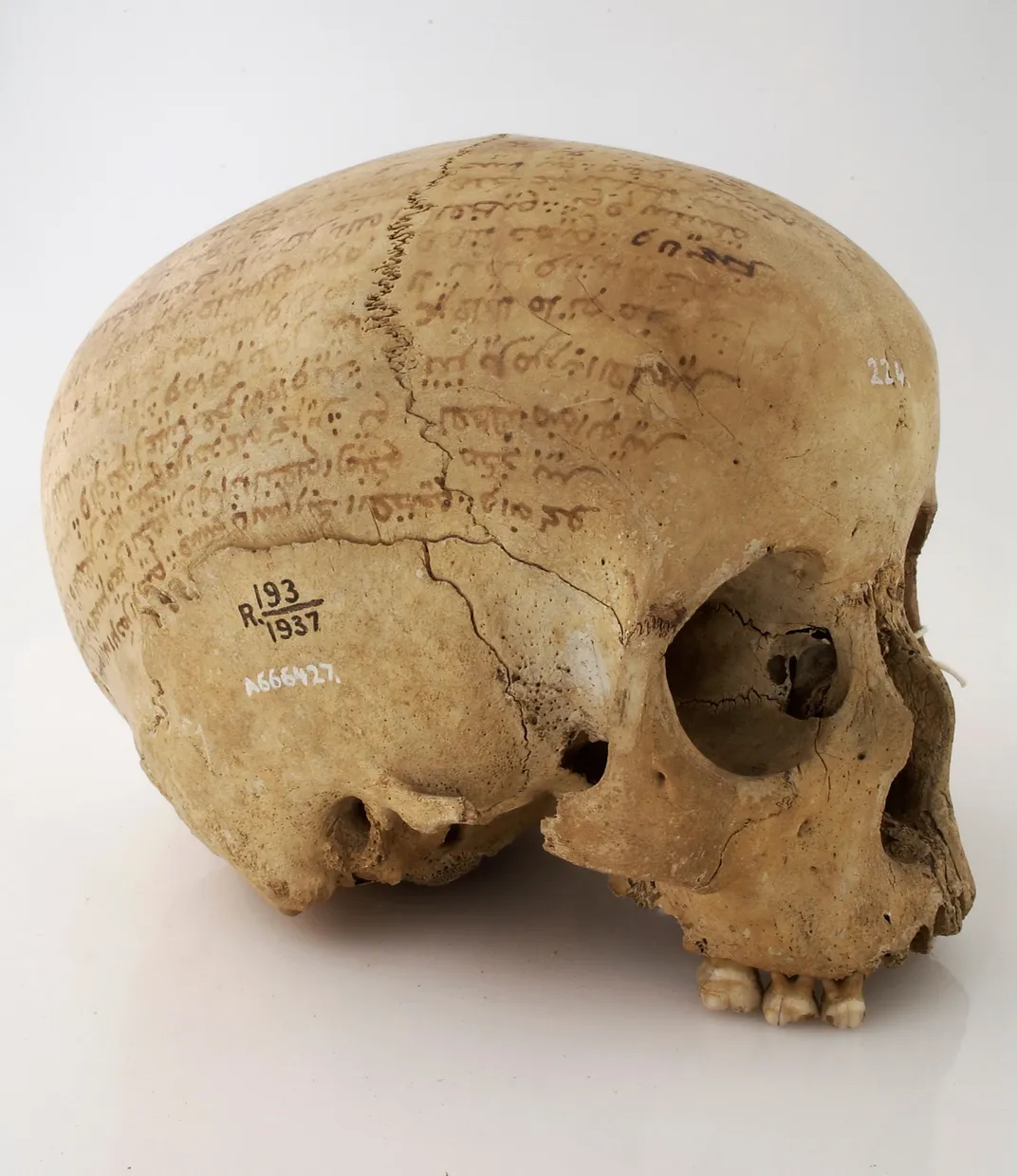

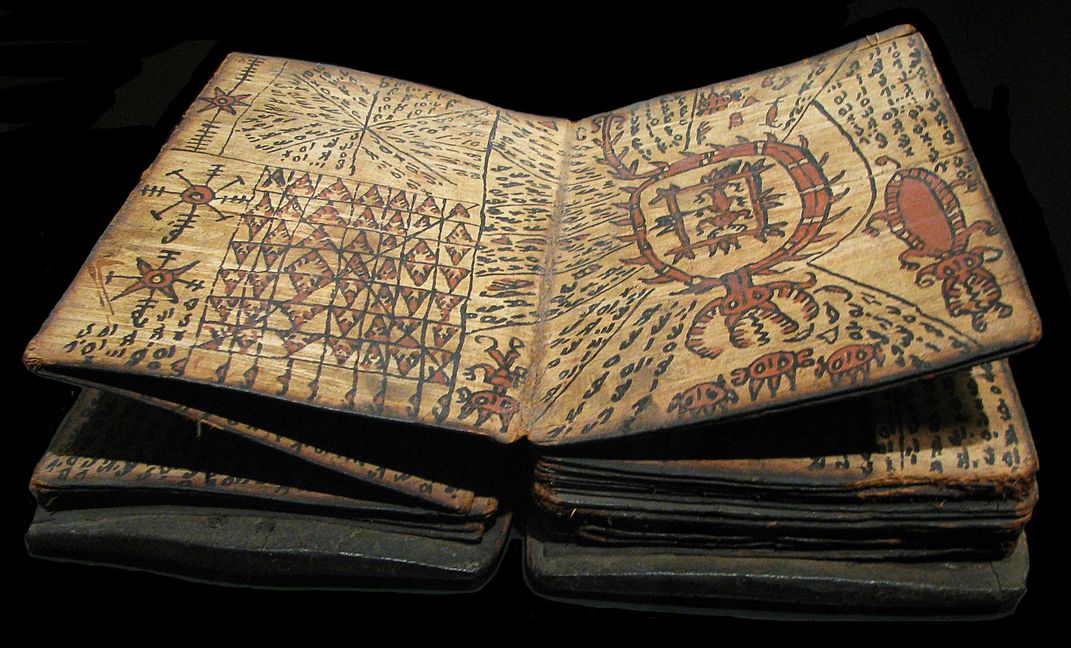

Other chapters of the book just naturally coalesced. There are books that aren’t books, looking back for anything that totally smashed the traditional understanding of what a book is, how do we define a book? We go through pre-codex, [a predecessor of the modern book,] looking at some of the earliest forms of writing, like these magical six-inch clay cones that look like large nails and are inscribed with cuneiform prayers currying favor with the gods. They served a practical purpose: When you were erecting a new building in the region, which is now Iraq, you would hammer thousands of these “magical” cones into the foundations of your building, and the gods would imbue your structure with protection against natural disaster.

Just taking this idea of strange books, it actually leads you around the world into different cultures. You realize everyone has their own form of curiosities, and that as a species, we’ve always been incredibly strange and weird, but also very funny and endlessly imaginative. So that’s what the book is really supposed to do—show and celebrate this depthless capacity of human imagination, show how paper is a kind of psychic capacitor holding all of these personalities that are alive the moment you open them, even though their authors have been dead for maybe a thousand years.

How did you track down so many titles for your collection?

It’s from talking to a lot of people who love sharing their expertise in the particular things that caught their eyes. So when I had the story of Saddam Hussein’s blood Quran, [a copy of the Islamic holy text purportedly penned using the Iraqi dictator’s blood as ink,] the whole point was to think when you have a strange book like that, what would be on the shelf beside it?

That’s quite a challenge. But I remember talking to a London book dealer at Maggs Brothers, and she said, “Oh, yes, speaking of books written in blood, we have a copy of a journal from a shipwreck from the early 1800s, the wreck of the Blenden Hall.” And it was an extraordinary story, because the captain managed to make it to shore on this island [in the South Atlantic] called Inaccessible Island. He wanted to keep a journal of what had happened. He had a writing desk and sheets of newspaper that had washed up, but he didn’t have any ink. And so the subtitle of this journal is Fate of the Blenden Hall, written in the blood of a penguin.

Then you discover that in the 1970s, there was a Marvel comic book featuring the band Kiss that was written with blood extracted from the band members, and you go off on these zany journeys. It’s from talking to people, going to rare book fairs. It’s a bit like a geode: You crack it open, and suddenly there are all these glittering things inside. It’s a very exciting form of discovery.

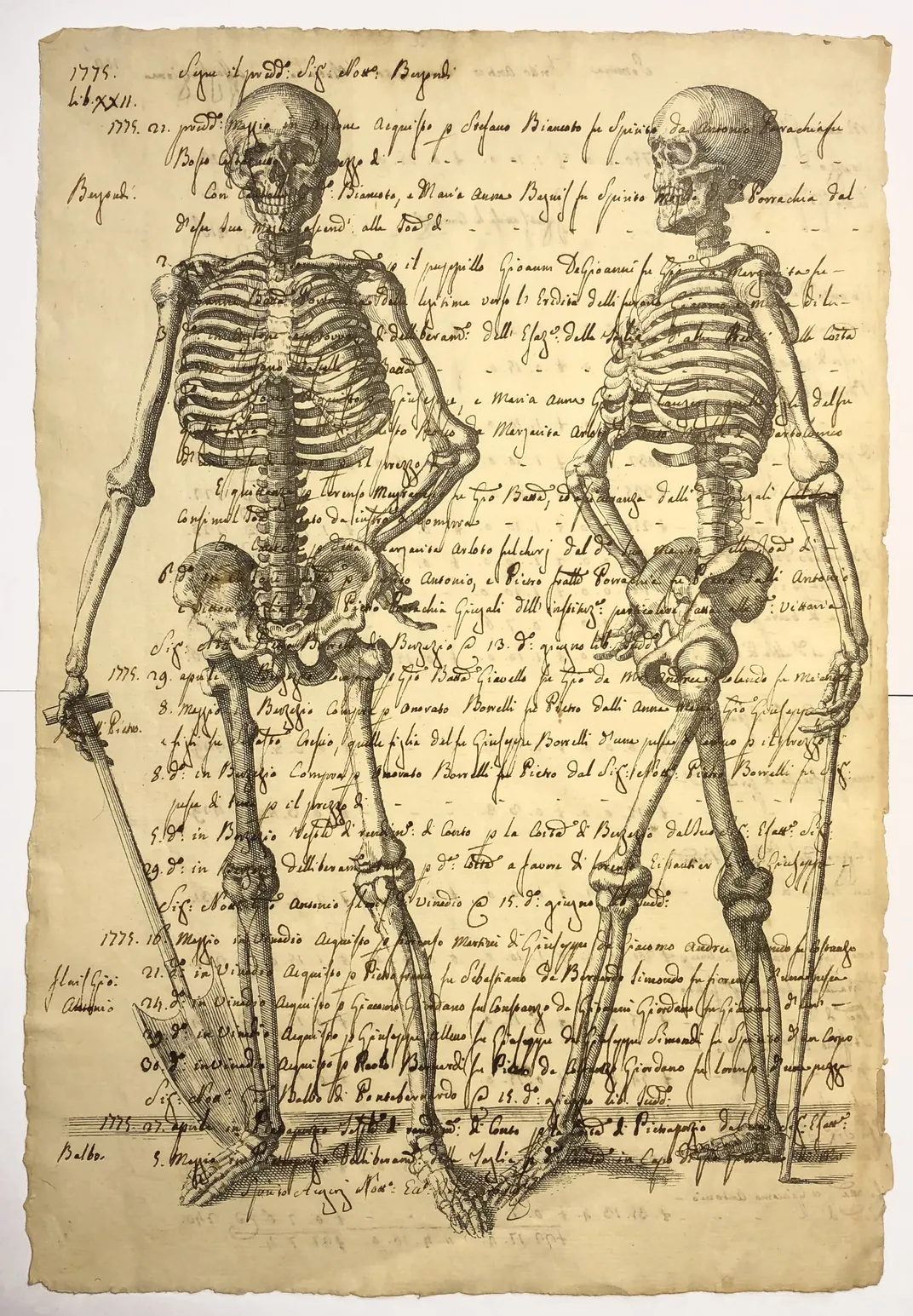

One of the most macabre practices featured in The Madman’s Library is anthropodermic bibliopegy, or the art of binding books in human skin. Where did this tradition originate, and what did it signify?

That was something I’d always been interested in but assumed was mostly rumor. It’s something that, to our modern sensibilities, seems unthinkably gruesome. And it also has a terrible association in the 20th century with the Nazis. But the fact is, for centuries, it was an accepted—I don’t know how acceptable, but it was accepted—decorative extra offered by printers and binders.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/4d/f74dd73d-b5f3-4ac1-b3ef-d67a6569ac52/a_book_bound_in_human_skin_-_de_integritatis_et_corruptionis_virginum_by_severin_pineau_printed_in_amsterdam_in_1663_credit_wellcome_collection.jpg)

Initially, I give a potted history of it, showing that it’s mainly strange medical cases. The doctor or the surgeon who performs the autopsy keeps a sliver of the skin of the subject to record unusual cases. Then there are criminal accounts, like the famous Massachusetts highwayman James Allen, from the 19th century, whose last wish before his execution was that a copy of his autobiography bound in his own skin should be presented to his one victim who fought back as a token of his admiration.

With criminals, it was about being both a deterrent and a more symbolic punishment, to encase the outlaw with the very symbol of civilization: the book. But in the late-19th century, the practice became more associated with the idea that a human skin binding could encase great writing like the body encases a soul.

One of the most striking stories was that of the French astronomer and writer Camille Flammarion, who was at a party when he complimented a passing young countess on the charm of her skin. It turned out that she was dying of a terminal illness and was a great fan of his. A few weeks later, after her death, there was a knock on his door. It was a Paris surgeon with a bundle under his arm, saying he’d been instructed to flay the “most marvelously attractive young woman,” and here was her skin, which she’d asked to be delivered to Flammarion for him to bind a copy of his latest work.

The Madman's Library: The Greatest Curiosities of Literature

This fascinating and bizarre collection compiles the most unusual, obscure books from the far reaches of the human imagination.

THE BOOKS

La Confession Coupée

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/d0/21d06c06-0110-4544-ab0b-d33325a7eb92/confession_coupee_credit_authors_own.jpg)

This palm-sized religious text—first published in 1677 but so popular that it remained in print until the 1750s—functioned much like a modern coupon book. (The edition featured in The Madman’s Library dates to 1721.) Instead of offering discounts on purchases, however, the cut-out confessional contained a comprehensive catalogue of 17th-century sins, each printed on a foldable tab for easy reference. If the volume’s owner was scheduled to attend confession but had no misdeeds to confess, they could simply turn to a random page and tear out an entry from the list of sins.

Says Brooke-Hitching, “They’re interesting books to come across now because you can get an insight into the previous owners’ lives and the things that they were afraid of, … [like] having bad intentions or being too vain or worrying about not being as young as one was.”

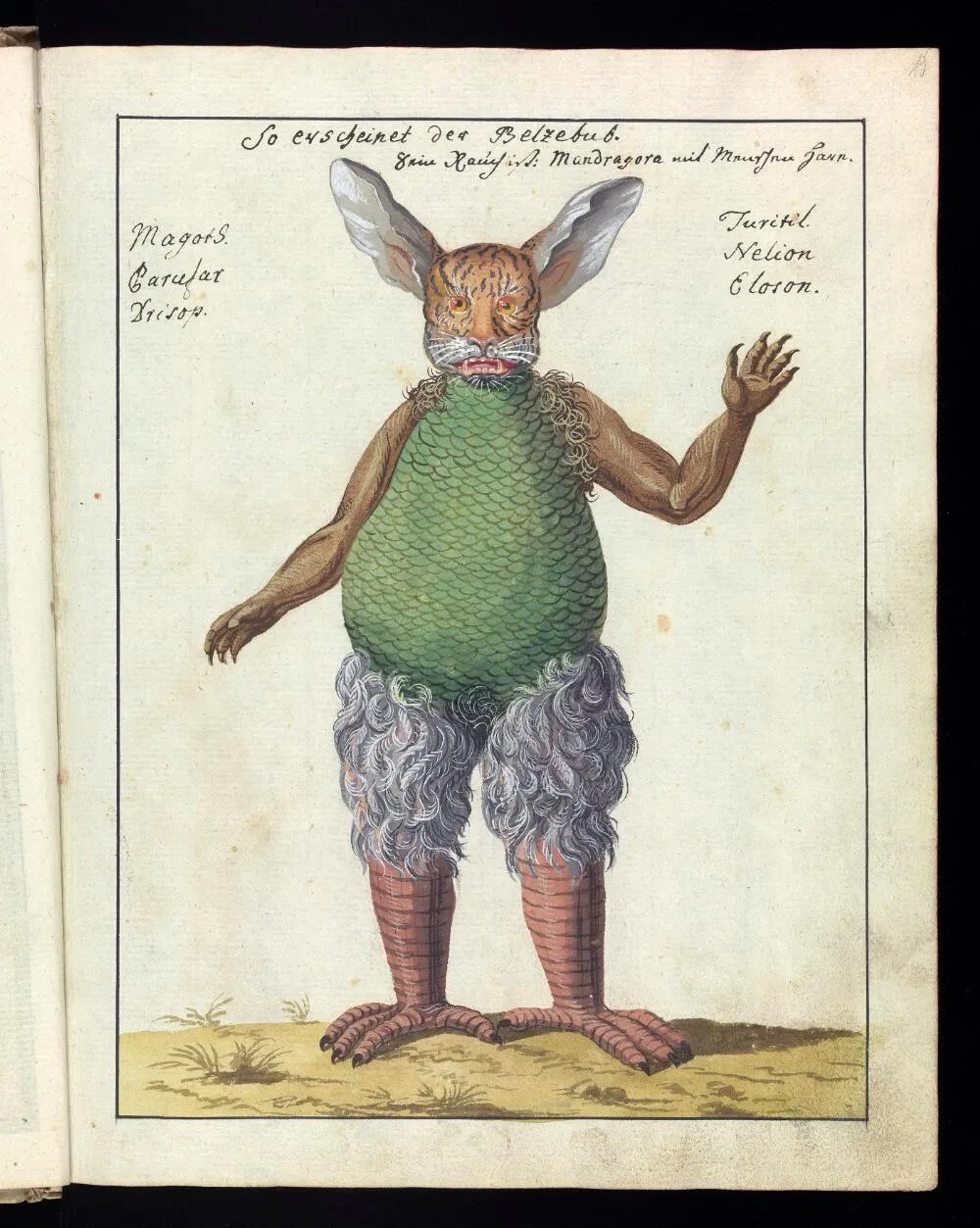

Compendium of Demonology and Magic

Housed in the Wellcome Collection, this “extraordinary” grimoire, or textbook of magic, is one of Brooke-Hitching’s personal favorites. A late 18th-century volume written in both Latin and German, the Compendium “served as a cautionary tale of the dangers of magic, even though it was produced [after] the hysteria of witch hunting had subsided,” he says.

“It was still quite fashionable at the time to use spell books for treasure hunting,” the author adds. “The idea was you would summon a demon who would guide you to buried treasure. There’s an illustration of two people doing just that, but it’s gone terribly wrong because this nine-foot demon has appeared ... and he’s grabbed one of the treasure hunters by the head [and] is urinating on their fire.”

The journals of Constantine Samuel Rafinesque

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/31/e331d954-8870-454c-95f3-54d8ba2e5ccc/6a01156e4c2c3d970c01a5119168a9970c-800wi.jpeg)

In the summer of 1818, Turkish naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque arrived at ornithologist John James Audubon’s Kentucky home for a friendly visit. Unfortunately for both men, Rafinesque greatly overstayed his welcome, prompting his hapless host to come up with a masterful plan of revenge. Rafinesque “kept pestering Audubon to show him the local American wildlife,” says Brooke-Hitching, “[and] he got so annoying that Audubon started making up animals and describing them to Rafinesque, who would faithfully, completely gullibly, just record them and draw them in his journals.”

When Rafinesque returned home, he decided to publish his “findings,” which featured such fanciful creatures as the bulletproof “Devil-Jack Diamond fish” and the “Big-mouth sucker.” The prank had unexpected consequences for Rafinesque and Audubon, both of whom lost credibility due to the incident.

Kampfreime

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/46/22466c54-3097-4487-8fa7-e193d0730d41/kampfreime_credit_beinecke.jpg)

Created by student protesters in Germany in 1968, this volume of “battle rhymes” and chants doubled as a weapon that could easily be concealed in one’s pocket. Its sharp metal binding, says Brooke-Hitching, came in handy when scraping “off propaganda posters from walls [or] defend[ing] yourself if you were about to be bundled into the back of a van by shadowy government agents.”

Xylotheks

Centuries before the Svalbard Global Seed Vault began preserving the world’s diverse crops, these book-shaped wooden containers—known as xylotheks—kept plant specimens safe, albeit on a much smaller scale. Tucked within the texts were samples from the trees used to carve them, including dried leaves, seeds, moss and branches. “It was the earliest kind of biodiversity storage collection,” Brooke-Hitching notes. “They’re fascinating—and incredibly pungent.”

Histoire des Pays Bas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/b2/00b26a8a-3b3c-4773-98bc-120ca2fa0da7/histoire_des_pays_bas_credit_daniel_crouch_rare_books_and_maps.jpg)

Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader meets a porta potty in this 18th-century book, whose French name translates to A History of the Low Countries. As the author explains, he was discussing “loo books,” or titles that are ideal for trips to the bathroom, with rare book dealer Daniel Crouch when Crouch mentioned that he was selling “an actual loo book.” Bound in gilded leather, the oversize oak volume transforms into a toilet for use on the go. “You unfold it, and it turns into a commode [that] you pop your little bowl beneath,” says Brooke-Hitching.

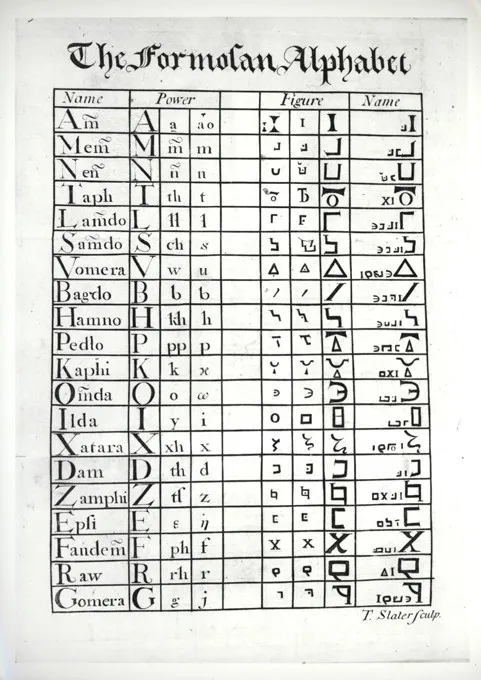

An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa

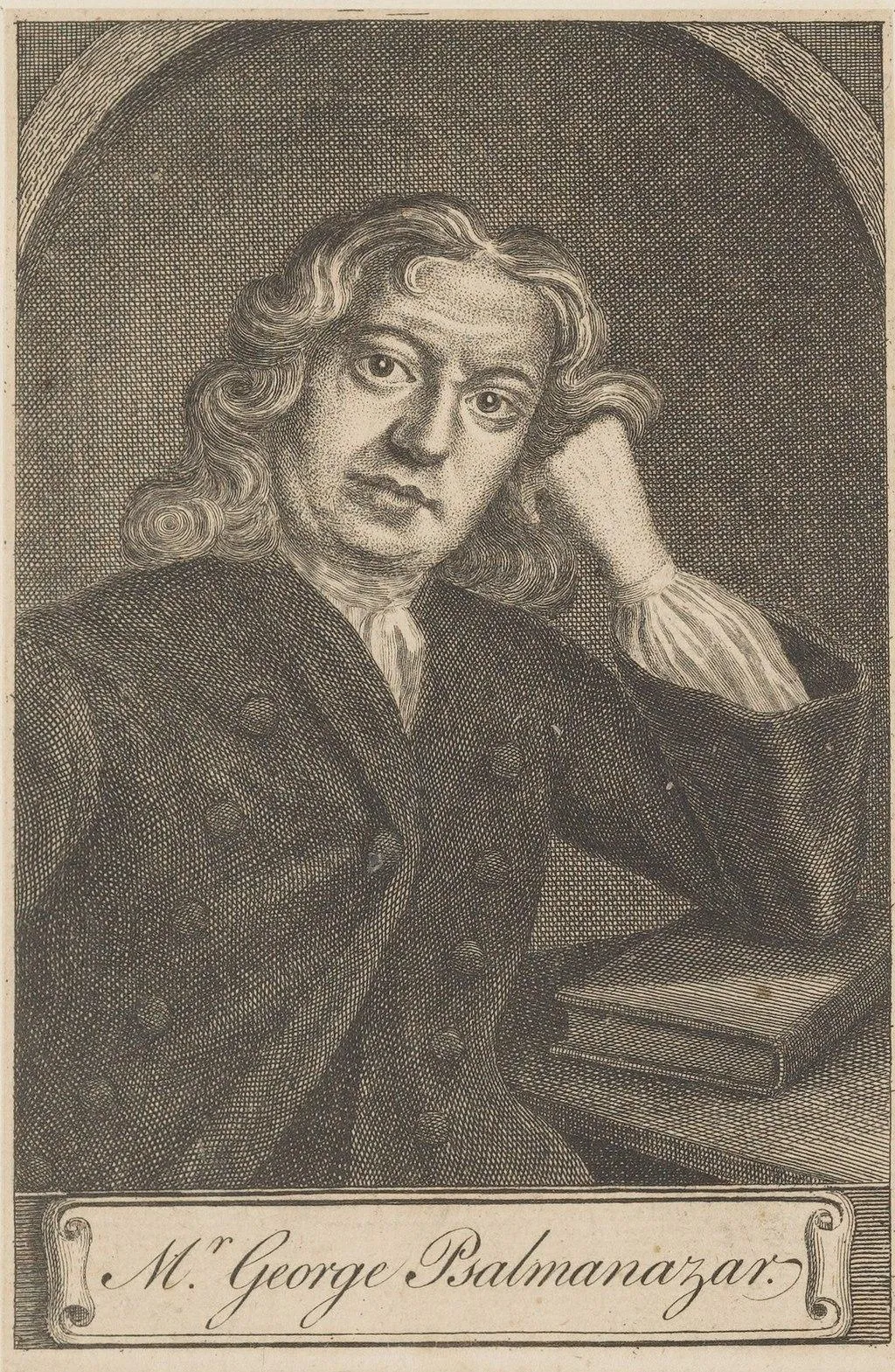

Around the turn of the 18th century, George Psalmanazar, a blond-haired, blue-eyed white man with a thick French accent, tricked London’s elite into believing that he was the first native of Taiwan, then known as Formosa, to step foot in Europe. In support of this far-fetched tale, Psalmanazar—who was, unsurprisingly, actually just a French con artist—penned an illustrated book about his “home country,” complete with a detailed, thoroughly made-up version of the Formosan language.

Psalmanazar’s account of being kidnapped from Formosa by Jesuits who pressured him to convert to Christianity attracted much suspicion, with skeptics such as astronomer Sir Edmond Halley (best known as the eponym of Halley’s Comet) calling parts of his story into question. But as Brooke-Hitching points out, “No one could correct him because they’d obviously never been [to Formosa] themselves.” The author adds, “He was the toast of London high society and became great buddies with [Samuel] Johnson, who was asked, ‘Did you ever think of him as an imposter?’ And Johnson said, ‘I would have sooner thought to have questioned the pope.’”

Disillusion of Sinners

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/44/3e4438db-00f3-4ca4-ad84-8baa858bdec6/ear_torture_in_hell_credit_john_carter_brown_library.jpg)

Brooke-Hitching was wandering through London’s Covent Garden district when he happened upon a print shop that sold illustrations from 18th-century Jesuit priest Alexandre Perier’s rare Disillusion of Sinners. The text details “the tortures that the sinner will suffer in Hell, but they’re all sense-based,” he says. “So there are images of demons blowing their infernal trumpets and hellhounds barking, all of [these] terrible sounds. … It’s the most terrifying imagery I think I’ve ever seen—incredibly effective, even today.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(294x165:295x166)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/ba/c6baa8d7-69c7-40c2-99b1-cf5ff6eec6a8/mobile_mad.png)

:focal(571x280:572x281)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/97/92979915-4fa4-4881-b2d5-acf7162e2bdd/so_cial_mad.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)