American Food Posters From World War I and II

Cory Bernat is the creator of an intriguing online exhibit of American food posters related to World Wars I and II

Cory Bernat is the creator of an intriguing online exhibit of American food posters related to World Wars I and II, culled from the National Agricultural Library's collection. Blogger Amanda Bensen recently spoke with her about the project.

What kind of messages about food was the government sending to the American public through these posters?

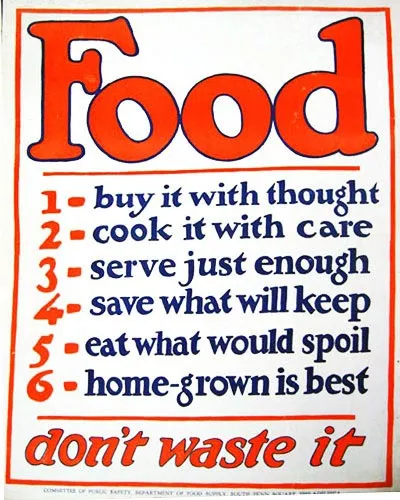

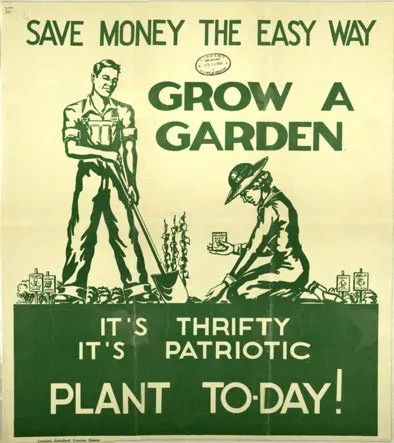

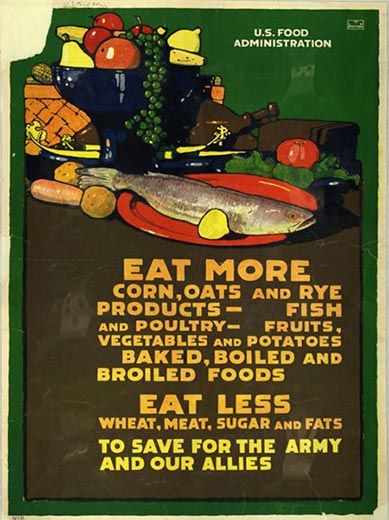

Bernat: Actually, as a professor pointed out to me, most of them are not really about food—they're about behavior modification. Both times, with both wars, the government needed the public to modify their behavior for the national good. (And today, that’s exactly what Michelle Obama is trying to get people to do: change their behavior to curb childhood obesity.) As the Food Administration's publications director put it to state officials back in 1917: “All you gentlemen have to do is induce the American people to change their ways of living!” He’s saying it with irony, of course, because that's a very hard task.

Talk about what some of the specific posters mean. Any favorites?

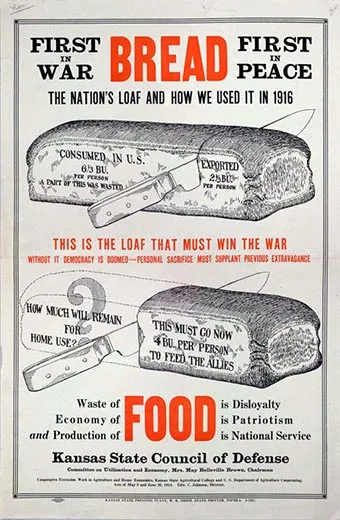

I have a preference in general for the World War I posters because they're just more informative. Look at the one called "Bread: The Nation's Loaf and How We Used It in 1916." This is a really impressive infographic, and it’s only a state poster, from Kansas. Not only is the text informative—it tells you how many bushels of wheat per person are consumed in the U.S.—but they've used true imagery. And on top of that, there are the strong messages: "Economy of food is patriotism," and "Without it democracy is doomed; personal sacrifice must supplant previous extravagance." What incredible statements! I like to wonder what people would make of this today.

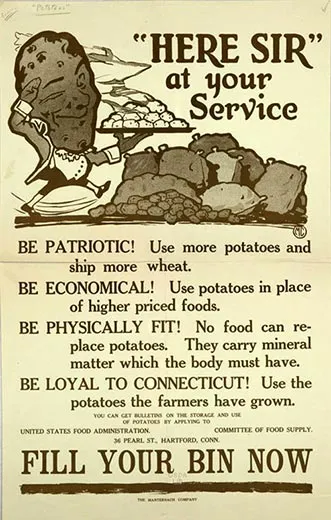

I also like the one after it in the online gallery. The saluting potato alone would be enough, but the information is good, too. And that “Be Loyal to Connecticut” line is basically telling people to eat locally—this was almost 100 years ago!

Then there's one from Arizona called "Good Eats" that urges people to preserve and eat more "perishables" than "staples" , and it says this will bring both savings and "fewer doctor bills." That’s a really prescient poster, and it strikes me as a good message for a contemporary audience. We’re rarely encouraged anymore to make the connections between diet and health and expense.

I notice there are also some posters from the years between the two World Wars. What issues did those address?

Well, take the one that says "America Has Plenty of Food," from the 1930s. That's at a time when the FDR administration was trying to achieve some parity between the price of food and the price that farmers were paid for that food. Increased production during World War I had put farmers into debt, buying land and equipment—and then there was a depression after the war, and farmers were in this terrible position of not being able to sell what they were growing.

So FDR began paying farmers to not grow things, and this poster was a way to reassure everyone that his policies were working—yes, we are paying farmers to not grow, but don't worry, there’s still enough food for everyone. See that flag in the background? It's from the "Ever-Normal Granary." That's a nice touch.

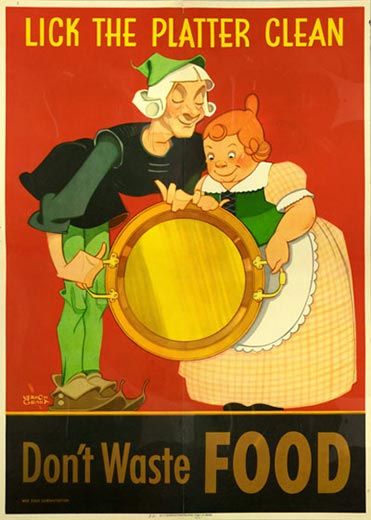

There are a lot of posters with the theme of reducing food waste, eating scraps and even saving "used fats" for the war effort. It’s kind of amazing how quickly things have changed.

Yes, one of the interesting questions this could lead to is, why is there no similar communal effort or awareness today, when we are technically at war? Even soldiers, I’ve heard, find that a little disheartening. I would almost call these messages subversive now.

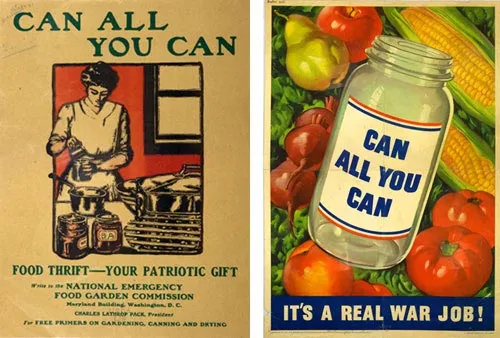

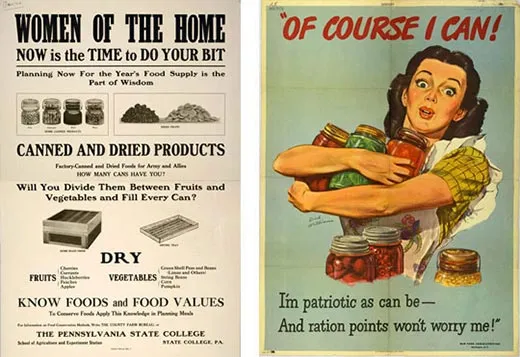

Putting these posters in chronological order showed me how the government's methodology changed over the years, and how they borrowed from professional advertising and were influenced by what was going on in the private sector. It also really shows the shift to an industrialized food system. You look at the WWII posters and think—where are the agriculture ones? Well, there aren’t any. It’s suddenly about consumers, not farmers.

Was anything consistent?

One thing that remained consistent was the use of women. Women are all over the food ads, still, today. And canning was very consistently popular as a topic because it was comforting. It was a way to show abundance instead of sacrifice, and these very typical, homey kitchen scenes with a woman in an apron. That’s not Rosie the Riveter.

How did you become interested in these posters? Did you know the Ag Library had such a collection?

Basically, it was a lucky find. I started this project in 2007 as a paper in a museum studies class, and it evolved into my thesis for a master’s degree. A history professor who heard I was interested in food history suggested that I check out the agricultural library up the road . When I went to look, what I found was a pile of unprocessed posters. The library didn’t even know what they had. But that was good for me, because it forced me to really study them. It allowed me to combine my research interests with my background in graphic design. And it helped that I had the structure of grad school to force me to propose some sort of project.

I took little snapshots of all the posters I thought I might want to study, and I had them all spread out on my floor, trying to figure out where they all belong in relation to each other. My professor wanted to know: What are you going to say about them? And I didn’t know at first, which was kind of unusual. Most historians begin with text and find visual material to illustrate it—I was doing the flip.

I tried to view this as real curatorial work, looking at them in historical context and telling the story in a way that means something to today's audience, but also explains how they would have been viewed at the time.

I’ve been working on it, donating my time for about 2 years, and it has gone through several iterations.I ended up covering an unusually large time period for just a master’s thesis, but I’m glad I did! I’m pleased with the result. I’m still learning things.

Were your professors pleased, too, I hope?

(Laughs). Yes, I got an A, and I graduated in December with a master's in cultural history and museum studies. Now, in my day job I’m a project archivist at the National Park Service, but I’d like to work in exhibit design.

Well, you've done a great job with this online exhibit. Will it ever become a physical exhibit, too?

It goes on display from June 21st through September August 30th at the National Agricultural Library in Beltsville (MD), and will eventually move to the USDA building in downtown DC. The originals can't be shown, because they are too light-sensitive. But I was actually glad when I heard that, because I don’t think these posters should be shown in a conventional, framed way. I want to show them as the mass-produced objects that they were, so I'll be pasting them on fence panels.