A Celebration of Cypriot Culture

Cyprus commemorates 50 years of nationhood and 11,000 years of civilization with an exhibition of more than 200 artifacts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Cyprus-Sophocles-Hadjisavvas-631.jpg)

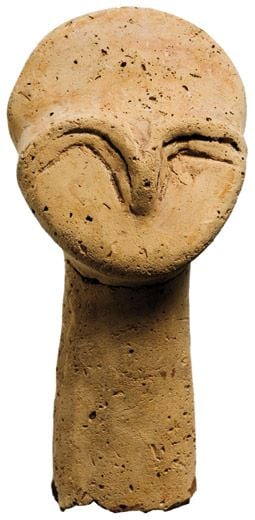

Sophocles Hadjisavvas circles a display case containing a 4,000-year-old ceramic jug. Hand-pinched clay figures sprout from its top: a man stomping on a tub of grapes as another collects the juice, two bulls pulling a plow and three laborers kneading dough. Excavated from a tomb in Pyrgos, a town on the northern coast of Cyprus, the jug predates the earliest known example of writing on the Mediterranean island by at least 450 years. “This vessel is very, very important,” says Hadjisavvas. “It shows what life was like around 2000 B.C.”

Which is precisely what Hadjisavvas has been trying to do as guest curator for the National Museum of Natural History’s exhibition “Cyprus: Crossroads of Civilizations” (until May 1). For the show he selected some 200 artifacts—pottery, tools, sculptures, jewelry and paintings—representing everyday life from the time of the first settlers’ arrival from the Anatolia coast (modern-day Turkey) around 8500 B.C. to the 16th century A.D., when it became part of the Ottoman Empire. He handpicked each object from Cypriot museums and centuries-old monasteries—a process he compares to finding the right actors for a play.

“He makes it look effortless and easy, but it couldn’t have happened without someone of his caliber of scholarship,” says Melinda Zeder, curator of Old World archaeology for the Natural History Museum’s department of anthropology. Hadjisavvas, 66, has spent nearly 40 years excavating in Cyprus, where he was born, and where, from 1998 to 2004, he served as director of the Cyprus Department of Antiquities. Part curator, part archaeologist, he describes himself as a “museologist.”

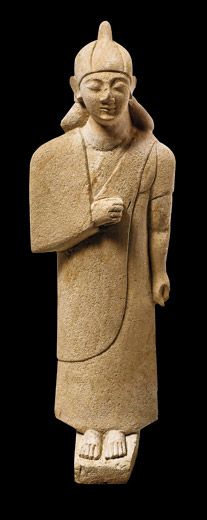

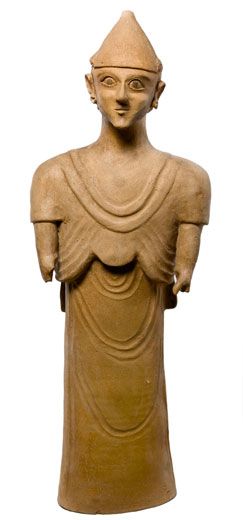

Hadjisavvas peels back some packing material in a wooden crate to reveal a helmet and beveled wing of a 900-pound limestone sphinx, explaining how it and a matching sphinx in a neighboring crate likely stood guard 2,500 years ago at a tomb in Tamassos—formerly an important trading city that was mentioned by Homer in The Odyssey. Next, he turns a small bowl so that a glass seam faces forward. The archaeologist has an eye for detail and admits that his first ambition was to be a painter. “But my instructor told me, you can paint for yourself,” he says. “Instead, you must find some way to help your country.”

For much of its history, Cyprus has been plagued by political instability. The Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Ottomans and British—lured by rich copper deposits in Cyprus’ Troodos Mountains—successively staked claims to the 3,572-square-mile island. Though Cyprus gained its independence from Great Britain in 1960, Turkey invaded and occupied the northern one-third of the country in 1974, ostensibly to protect the rights of ethnic Turks. The region, formally named the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, is not recognized as a state by the international community. Yet the history of Cyprus, as told by the Natural History Museum’s exhibition, is more than a timeline of conquests.

The easternmost island in the Mediterranean, it was a significant crossroads for European, Asian and African cultures. “Cyprus was always a melting pot, and still is today,” says Hadjisavvas. “It was a place where Hittites met Egyptians, Phoenicians met Greeks, and Jews meet Arabs.You can see this in the antiquities.”

Indeed, the ceramic jug decorated with clay figures is an example of “red polished ware,” a type of pottery from Anatolia. The upturned wings of the sphinxes reflect a Syrian influence, while the statues’ crowns and headdresses are distinctly Egyptian. And at the rear of the gallery is a marble statue of Aphrodite (born, according to legend, in Cyprus), sculpted in a classic Greek and Roman style.

Ironically for a country known as a crossroads of civilizations, the exhibition—which opened this past September to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the nation’s independence—marks the first time that a Cypriot archaeological collection of this magnitude has ever traveled to the United States. Hadjisavvas says that though the island has a history spanning more than 100 centuries, this is the year “we are coming of age.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)