The Dark Side of Glory

An early glimpse of PTSD in the letters of World War I aces.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/a7/1da74fcc-b839-455d-9770-b77d43c5d69a/mannock.jpg)

“I zoom up violently, the pressure pushes me into my seat, my sight goes for a second, then more shots, they’re both at me, I’m skidding madly, zooming, doing flat turns, quick rolls, anything to stop them getting a bead on me, throwing the poor old Pup around, my gentle sensitive Pup, her startled shudders of protest almost hurt, but there’s no smooth flying in a shambles like this, it’s ham-fisted stuff or you’re out.” –Arthur Gould Lee

The Great War was in its second year and was not going well. Troops were mired in the mud and blood of trench warfare, and a despondent public desperately needed hope, leading many of them to look skyward.

Though aviation was in its infancy, little time had been wasted in fitting the day’s frail airplanes of spruce and canvas with machine guns, giving birth to a new phenomenon: aerial combat. Unlike the antiquated thinking that had led to the stalemate of trench warfare, aerial warfare was unfettered by old ideas. It was created in the moment, and pilots tested their ideas using their hides as collateral. If a new tactic worked, a new maneuver was born; if it didn’t, the man conceiving it often died. Those who excelled at the new type of warfare gave birth to a new term: ace.

The mythology of the ace generated hope that aerial warfare might save the day. It’s a mythology that lives on. Tom Crouch, an aeronautics curator at the National Air and Space Museum, notes that even though World War II remains one of the most documented wars in collective memory, few can remember the names of the pilots who became aces in it. In contrast, almost everyone has heard of World War I’s Red Baron (German ace Manfred von Richthofen).

The Great War’s aces won lasting fame, but success came at a price. When these pilots confronted their humanity, their victims, or both, they often suffered, and each man had a finite amount of emotional capital and courage. Renowned English physician Charles Moran noted that “men wear out in war like clothes.”

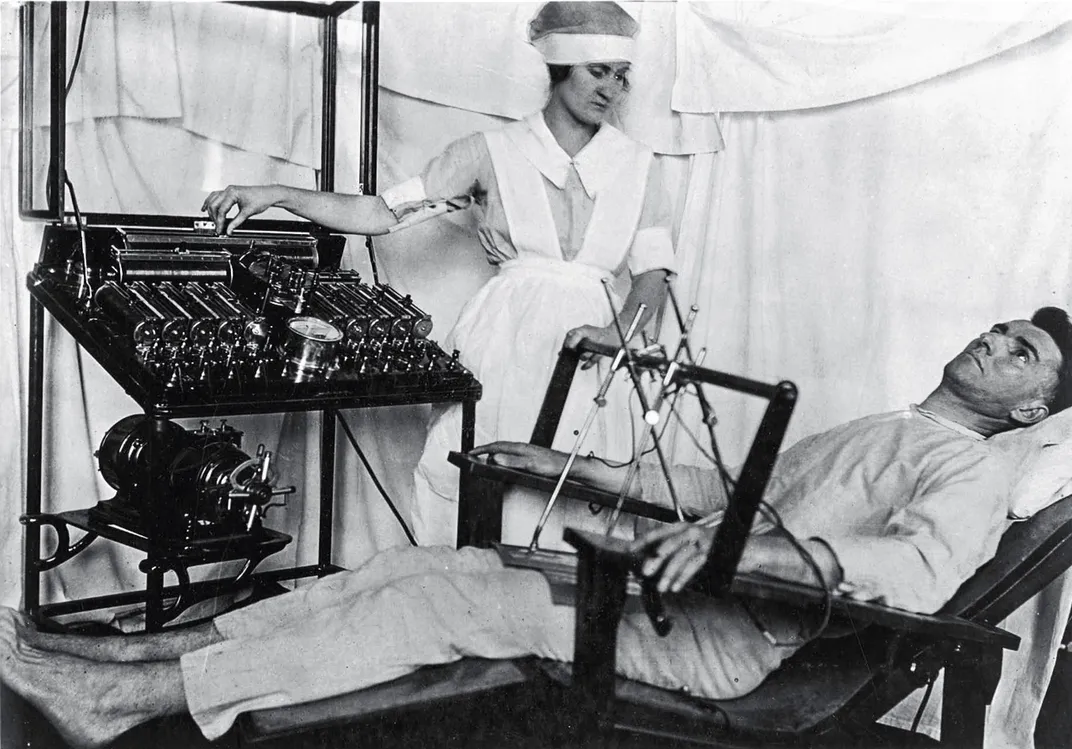

Combat stress among fliers, known then as “aero-neurosis,” became more common as the war progressed. Psychological stress, combined with the little-understood effects of high-altitude flying such as hypoxia, often resulted in airmen being removed from duty and sent to one of many convalescent hospitals that had popped up across the French and British countryside.

The field of combat aviation psychiatry evolved symbiotically with the war. The diagnosis and treatment of both ground and aerial disorders was skewed toward quickly returning the men to the trenches and cockpits. As the war continued, militaries of both the Allies and Central Powers began to create hospitals specifically for fliers. One of these—Number 24 Royal Air Force General Hospital—is mentioned by Canadian pilot Captain Roy Brown: “It is on a hill close to Hampstead Heath. They do a lot of research work here into the different kinds of troubles which are peculiar to flying people. It is purely for [Royal Air Force] officers, so they get lots of material to work on. It is a very good idea having a hospital like this [because] in an ordinary hospital, they do not know how to treat the troubles of flying people.”

Many such as Brown were discharged from the hospital to serve in a reduced capacity as flight instructors, while some were granted a series of leaves as military and medical leadership debated what to do with them. Treatment and diagnosis tended to focus on the airmen’s various physiological disorders, while downplaying their damaged psyches. And these compromised airmen were virtually ignored in the press; news stories about psychological suffering were considered counterproductive to the war effort. Furthermore, mail from fliers and troops to their loved ones back home was often censored. In one letter Brown writes about attacking an enemy: “I don’t know how much of this the censor will allow. I have never written anything like this before, but there is really nothing in it that can do the enemy any good so it should go through.”

Those who fought in the air above France knew they were a breed apart—not necessarily better than those on the ground, just different—and that what they were doing was best done during the summer of their lives. Arthur Gould Lee had this to say about his experience as a Royal Air Force pilot: “Those of us who were to pass safely through this strife and bloodshed would be affected by it all the rest of our lives. Although maybe I’d not matched up in achievement with the best, I was there with them. It was my crowded hour of glorious life.”

After the war ended in 1918, many pilots’ letters were published, and when the early aces could not put their pain into words, their friends sometimes did it for them. The following five pilots did not hold back in revealing the psychological suffering so prevalent among their kind.

**********

John MacGavock Grider was one of 210 cadets who joined the aviation section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps shortly after the United States entered the war in 1917. Volunteers from the group were sent to England for training. In May 1918, Grider was assigned to Royal Flying Corps 85 Squadron, where he downed four enemy aircraft. On June 18, he was killed in action. After his death, his letters were edited and published by his friend, Elliott White Springs. “I can’t write much these days,” wrote Grider. “I’m too nervous. I can hardly hold a pen. I’m all right in the air, as calm as a cucumber, but on the ground, I’m a wreck and I get panicky. Nobody in the squadron can get a glass to his mouth with one hand after one of these patrols. Some nights we have nightmares. We don’t sleep much.”

By the time Grider wrote the following entry, he was already a man forever changed: “It’s only a question of time until we all get it. I’m all shot to pieces. I only hope I can stick it out. I don’t want to quit. My nerves are all gone, and I can’t stop. I’ve lived beyond my time already. It’s not the fear of death that’s done it. It’s this eternal flinching from it that’s doing it, and has made a coward out of me. Few men live to know what real fear is. It’s something that grows on you, day by day, that eats into your constitution and undermines your sanity. I have never been serious about anything in my life, and now I know that I’ll never be otherwise again. Here I am, twenty four years old. I look forty and feel ninety. I’ve lost all interest in life beyond the next patrol.”

A few days later, Grider was shot down 20 miles behind German lines. He was given a decent burial by the Germans, and his grave was later found by the Red Cross. Death must have come as a relief to him.

**********

William Lambert volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps in late 1916. After training in Toronto, he was sent to Europe, and in March 1918 he joined 24 Squadron, which was stationed in France and had been outfitted with Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a fighters. Lambert flew and fought well. The war’s toll, however, became personal when his close friend and wingman Lieutenant J. Daley perished. “Daley was gone forever,” wrote Lambert in his book Combat Report, which was based on his diaries and logbooks. “We had been almost like brothers for three months and had worked together as a team of two. I can see him even now, on patrol, after doing something that pleased him. He would move in close to me, wingtip to wingtip, look over and wave to me with a wide grin covering his face. I would certainly miss Daley.”

By the following entry, Lambert is nearly at the end of his rope; his subconscious knows it but his conscious mind does not. “After yesterday, the nerves of almost every pilot in the squadron were about shot,” he wrote. “Most had been doing this work for three weeks. No one complained, but one had only to look into the face of a pilot and watch his actions. The story was there. During the fighting of the previous day, I had no time to think about it, but 24 hours later it was a different story.”

Lambert’s combat fatigue caught him by surprise, like a slow fuse finally reaching its charge. “Almost everything from that day [late August] until about October 1, 1918, is a blank,” he wrote. “I do not know what happened to me, only that I was suffering from the effects of combat fatigue. My recollection is of watching someone loading my gear into a tender. Later, I was swimming with another pilot on a long white, sandy beach. A woman in nurse’s uniform, strolling along the beach, joined us. She told us that it was a resort hotel—at Wimereux—and had been converted into a hospital [Number 14 Stationary Hospital]. We were patients there. This puzzled us. What were we doing there?

“Later I was in a London hospital [Queen Alexandra’s Hospital], evidently for the whole of September, being attended by two doctors. One had a slender, flexible wire contraption about twelve inches long and to which was attached an electric cord. This wire was inserted into, and pushed half way up, one of my nostrils, and it was explained as part of the treatment to the ruptured ear drums I had apparently contracted. I seem to recall enduring this most painful and extremely unpleasant torture about every second or third day for a period of several weeks. About the last week of September, I was told that if I wished, I could go home at my own expense for three months leave. You can bet that ‘I wished.’ ”

Lambert was finally discharged and returned to Ohio. He attempted to secure a pension from the Royal Air Force, but it took years to get and ended up being a pittance.

**********

Ernst Udet was Germany’s top ace after Manfred von Richthofen was killed. Udet was credited with 64 victories. He served in Jastas (fighter squadrons) 37, 11, and 4 and was in command of the latter two.

A sensitive and imaginative man, Udet confronted his humanity early in his evolution as a combat flier. His adjustment to the war didn’t go perfectly, but in the long run he seems to have fared better than other fliers. “Very soon he was so close that I could see the observer’s head,” wrote Udet in his memoir, Ace of the Black Cross. “With his rectangular goggles, he resembled some great, ferocious insect bent upon my destruction. The moment had now come for me to shoot in earnest, but I was quite unable to do so! It was as though horror had turned my blood to ice, taken the strength from my arms, and numbed my brain. I sat passively in the cockpit, flying straight ahead, and staring idiotically at the Caudron as we passed each other. ‘You miserable coward!’ the engine seemed to say. I had failed miserably at the crucial moment. I had thought of myself, and had trembled for my own safety. There and then, I vowed to rid myself of the stain that now lay upon my honor.

“The moment had come. My heart beat furiously, and the hand which held the joy-stick was damp. My Fokker flew above the enemy squadron like a hawk singling out its victim but did not pounce. But even as I hesitated, I realized that if I failed to open the battle immediately, I should never have the courage to do so afterwards. In that case I would land, go to my room, and then, in the morning, Pfalzer would have the task of writing my father that there had been a fatal accident while I was cleaning my revolver.”

It’s telling that Udet wrote about suicide. He did ultimately take his life, in 1941, when he felt that Hermann Goering—a comrade in arms and his squadron commander during World War I—had betrayed him during World War II.

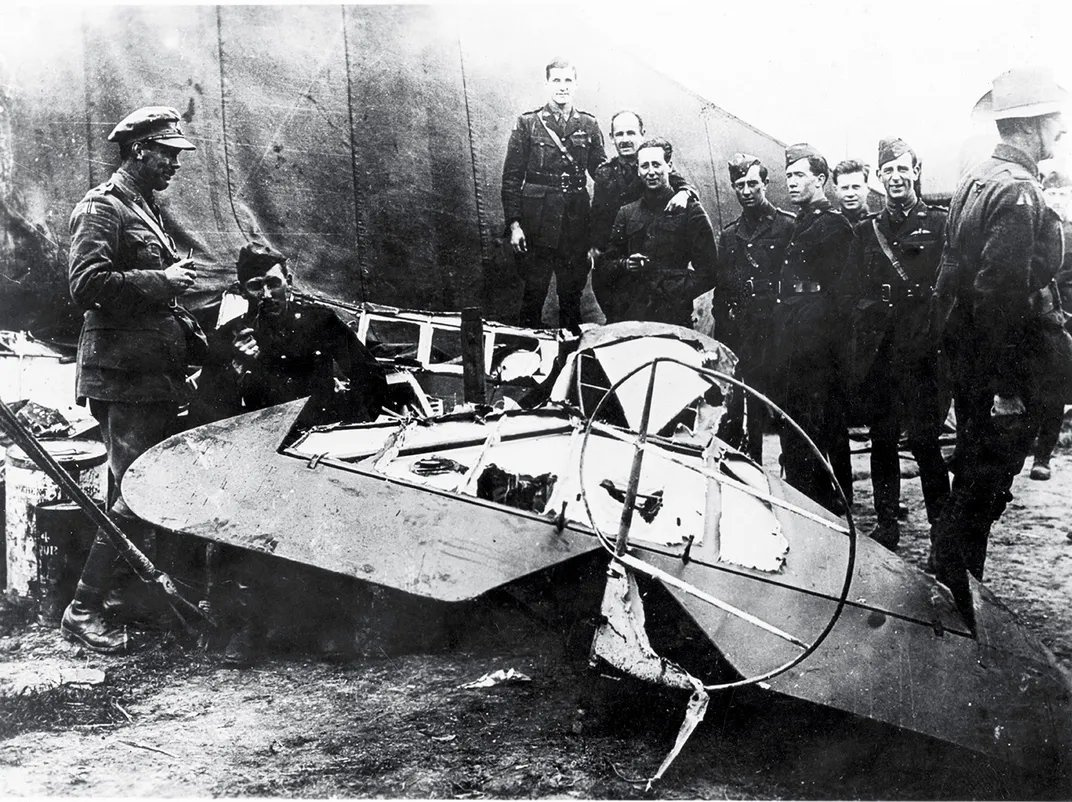

Udet, like so many pilots, succumbed to curiosity and anxiety about his victims: “I flew back to the aerodrome, my skin soaked in perspiration, and my nerves in a desperately excited state. I had made it a rule never to let myself worry about the men I shot down. He who fights should not look at the wounds he inflicts. But I felt an insatiable desire to know who my opponent had been. I made my way to the scene of the crash. My opponent had been shot through the head. The doctor handed me his wallet: Lieutenant C.R. Massdorp, Ontario, RFC 47. Also in the wallet were a picture of an elderly woman and a letter. It said: ‘Don’t be too reckless. Think of father and me.’ Somehow one had to try to get rid of the thought that a mother wept for every man one shot down.”

**********

Roy Brown was a Canadian flier who served with the Royal Flying Corps on the Western front. He was credited with 10 victories. Brown seems to have fought reasonably well, but after the Royal Air Force credited him with shooting down Manfred von Richthofen on April 21, 1918, Brown was shaken. The image of the German ace’s body had unhinged him. (The angle of von Richthofen’s bullet wound, however, suggests that the fatal shot came from ground fire, not Roy Brown’s gun.)

In a letter to his mother, Brown wrote: “The sight of Richthofen as I walked closer gave me a start. He appeared so small to me, so delicate. He looked so friendly. Blond, silk-soft hair, like that of a child, fell from the broad, high forehead. His face, particularly peaceful, had an expression of gentleness and goodness, of refinement. Suddenly I felt miserable, desperately unhappy, as if I had committed an injustice. With a feeling of shame, a kind of anger against myself moved in my thoughts, that I had forced him to lay there. And in my heart, I cursed the force that is devoted to death.

“I gnashed my teeth, I cursed the war. If I could, I would gladly have brought him back to life, but that is somewhat different than shooting a gun. I could no longer look him in the face. I went away. I did not feel like a victor. There was a lump in my throat. If he had been my dearest friend, I could not have felt greater sorrow.”

Shortly after von Richthofen’s death, Brown, experiencing exhaustion, checked into a hospital. In another letter to his mother, he wrote: “I do not sleep very well. While I was awake, the nurse came in. When I heard her, I jumped and was as frightened as a baby. After that, every little noise made me jump and frightened me the same. Please excuse me writing and telling you all this. I must unburden myself some time.”

Brown did not see action again, and after his recovery, he became a flight instructor. On July 15, 1918, he took an airplane for a practice flight and fainted in the air. His aircraft crashed from about 300 feet, and he suffered severe injuries but survived.

**********

Edward “Mick” Mannock, who came from working class Irish stock, championed a collectivist approach to fighter tactics: focusing on the good of the group versus individual achievement. And though the strain of combat had reduced him to a nervous wreck, he somehow managed to lead his squadron in targeting German pilots, while racking up 73 victories of his own.

On July 13, 1917, Mannock shot down a two-seat reconnaissance biplane. The victory afforded him his first close inspection of a victim. “I shot the pilot in three places and wounded the observer in the side,” he wrote. “The machine was smashed to pieces, and a little black-and-tan dog which was with the observer was also killed. The observer escaped death. The pilot was horribly mutilated. I felt exactly like a murderer.

“I don’t quite know how long my nerves will last out. I am rather old now, as airmen go, for fighting. These times are so horrible that occasionally I feel that life is not worth hanging on to. I had thoughts of getting married, but not now.”

Mannock had expressed these feelings to his friend Jim Eyles, who noted, when Mannock was home on leave: “His face, when he lifted it, was a terrible sight. Saliva and tears were running down his face; he couldn’t stop it. He smiled weakly at me when he saw me watching and tried to make light of it. He would not talk about it at all. I felt helpless not being able to do anything. He was ashamed to let me see him in this condition but could not help it, however hard he tried.”

Mannock wrote a letter to a Mary Lewis shortly before his final patrol. Contained in this excerpt is the notion that physical and mental anguish served a purpose: “I do not believe that the war & the ‘Great Push’ are things ‘rare and superficial.’ Strife & bloodshed & physical ‘exertion’ & mental anguish are all good, gloriously wonderfully beneficial things for the human race. These boys out here fighting are tempted at every moment of their day to run away from the ghastly Hell created by the Maker, but they resist the temptation and die for it, or become fitter & better for it, or because of it.”

Mannock’s last patrol was July 26, 1918. He and a new pilot were over Pacaut Wood when German rifle and machine-gun fire hit the port side of his S.E.5a, igniting the aircraft’s fuel. Mannock lost control, and the airplane crashed behind German lines near Merville. His body was taken out of his airplane and buried by German soldiers somewhere in northern France.