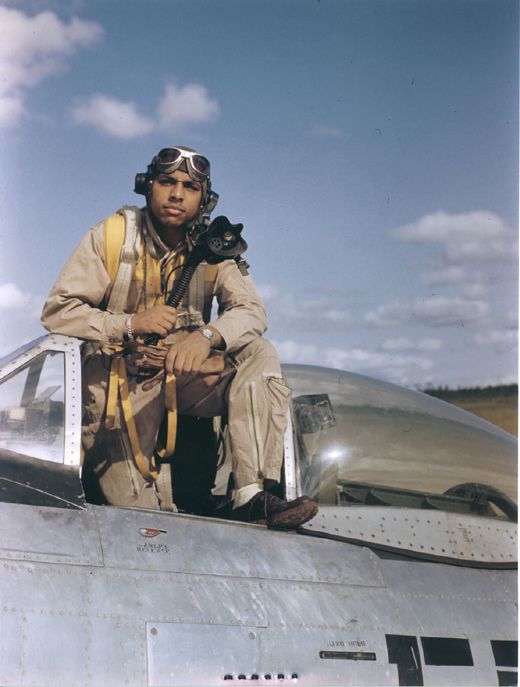

Tuskegee Memories

This World War II veteran loved flying all airplanes, but especially the Mustang.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/holloman-388-aug07.jpg)

William Holloman, a retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel and a Tuskegee-trained pilot now living in Kent, Washington, flew P-51 Mustangs with the 332nd Fighter Group in Europe during World War II. Holloman, who later became the Air Force’s first black helicopter pilot, plans to attend theColumbus, Ohio in September. He spoke with Air & Space associate editor Diane Tedeschi in July.

A&S: What did you like about flying the P-51?

Holloman: It was easy to fly. It wasn’t as much work as others I’d flown up to that time. I’d flown the P-40 and the P-47—they were harder than the -51. I used to tell people that my old-maid aunt could fly the P-51 because it was such an easy airplane.

A&S: How long did it take you to get trained in the P-51?

Holloman: They gave us the book to read, and we took two or three flights, then we went on a mission. I think I had probably seven, eight hours [of flight training]. If you could get if off the ground, they needed a warm body to fly it. They didn’t have the luxury of giving you a lot of training time.

A&S: Did you get your P-51 training at the Lockbourne base in Ohio?

Holloman: Oh, no. We did our training in the P-51 at Ramitelli, Italy, after we got overseas. [After that] we were flying into Germany and Austria and eastern Europe. We had three types of missions. Escort missions, to protect the bombers from enemy fighters. Strafing missions over ground targets such as trains and trucks. And search and destroy missions, which I guess we liked the best because we were able to attack targets of opportunity wherever they presented themselves.

A&S: Since the U.S. military services were still segregated during the war, you probably didn’t have much contact with the white U.S. bomber crews that you were escorting?

Holloman: When we went to town, we had lots of contact with them. In Italy, we were all stationed separately but within 25 or 30 miles of each other. They embraced us when we went to town. They wouldn’t let us buy our own drinks. They were very friendly. We were all brothers in arms in a combat area. Segregation didn’t show itself until we got back to American soil. You get off the boat, and it’s all right there. I don’t think that I really hated the social structure of the United States until I came back from Italy. It was kind of sad.

A&S: How did it feel to be flying combat missions?

Holloman: My thinking was: I was doing something that I enjoyed doing. I enjoyed flying. I used to tell a joke to audiences [during speaking engagements] that I wanted to fly so bad that if Adolph Hitler had let me fly, I’d have flown for him. But there were people that flew in the war that say they did it as a duty, as an obligation. I flew in the war because I loved flying. It doesn’t mean that I wasn’t looking toward the day when the war would be over, because I certainly didn’t like getting shot at. Every time we went out there, we got shot at. It was like playing Russian roulette.

A&S: What was your opinion of the German pilots that you encountered?

Holloman: Well, that’s a tough question because I thought I was pretty good. I never considered them being anything else other than well-trained. I talk to German pilots all the time in my travels—those that survived had to be good. I do know that I had respect for my enemy. I thought he had to be something special to be able to fly an airplane.