Slim Lewis Slept Here

Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, had one brief, shining moment when airmail pilots used it as a stopover. Then they went away, leaving only memories.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/51/495121d8-2497-45c7-a1fb-ac0d9fb6896d/bellefonte_nasm-2a38759.jpg)

The images still linger in their memories: the sound of an approaching motor, the mad scramble to the grassy field on the edge of town, the moment when the great light on the mailplane suddenly switched on, its beam flooding the waiting crowd. Finally the airplane would land, and as the ground crew closed in to refuel for the journey’s next leg, the pilot would climb ever so casually from the cockpit.

Was it really 60 years ago that mailplanes landed nightly in the little central Pennsylvania town of Bellefonte, bearing a cargo of life and pride and excitement? Was it that long ago and more that daredevil Slim Lewis buzzed the courthouse and made the fish-shaped weather vane spin, and handsome Max Miller roared around town in his green Nash roadster? The town was even tinier then (population 3,996 in 1920, 6,200 now), but during the 1920s it performed a vital service as the first airmail refueling stop in the nation. To be young in Bellefonte in those adolescent years of American aviation was to be part of something wonderful.

Jim Kerschner, 67, a former radio station manager and now Bellefonte’s mayor, is one of several men who grew up in that era and never got over their infatuation with flying. “You can’t conceive how exciting it was,” he says. “Every time I saw a plane I’d go look. The big kick was going to the field to watch the night mail come in. I’d nag my dad to take me even though it was way past my bedtime, and when I got older I’d ride my bike. There were usually 25 or 30 people there. In my six-year-old mind those pilots were gods. I never had the audacity to speak to them.”

Max Sampsell, a retired store manager, remembers teachers dismissing classes whenever an airplane landed. “My second or third grade teacher let any of us go who wanted to,” he says, “and we’d get there somehow even though the strip was three miles away. We’d cut across farm fields.” A B-29 gunner in World War II, Sampsell found the terrific illumination of the mail airplane’s headlight “brighter than anything I saw until I was over Japan in a bomber.”

For 87-year-old Edna Barger, Bellefonte’s glory years meant lobsters. Her father was a dentist who treated the pilots at discount rates; in return, the fliers brought him buckets of live lobsters from New York. “My father would come back from the field,” Barger recounts, “and the next thing I knew lobsters were crawling across the kitchen floor.”

“I’d hitchhike to the field with a friend pretty near every day after school,” recalls Jim Saxion, 78, who retired as a furniture refinisher at nearby Penn State University. “It was just fun, riding in the rumble seat to the field with our hair flying. We’d stay and watch until the mechanics went off duty. Other times we’d go to the train station to see the 8:16 come in from Milesburg. Those were our mainstays.”

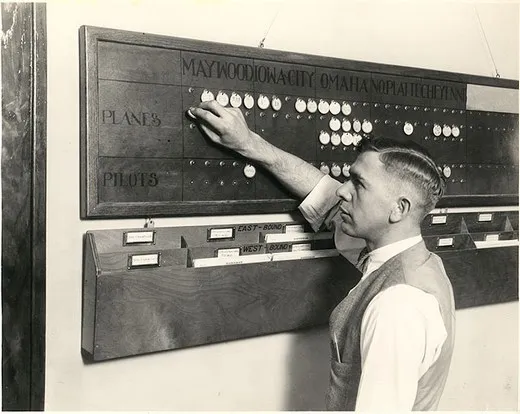

The seeds of Bellefonte’s glory were planted when the government began the Air Mail Service in 1918. That year the service sent veteran pilot Max Miller on a survey flight from New York to Chicago in search of a suitable refueling stop. Bellefonte residents were elated when the airmail operation chose their town, whose distance from New York made it a convenient landing spot for fuel-thirsty airplanes. Daily flights between New York and Chicago, with the first westbound refueling stop at Bellefonte and the second at Cleveland, began in the summer of 1919; transcontinental service was in place by 1920. When the Air Mail Service built a chain of beacons enabling transcontinental night flights in 1925, the Bellefonte installation was moved to a larger field southeast of town. By this time airmail operations had overcome a somewhat shaky start, reaching a peak of efficiency and public acceptance. These were the days of daring lone mail pilots struggling in fragile biplanes against bad weather and inhospitable terrain. Indeed, airmail charmed the entire country. In 1924 postal workers in San Francisco declined to mail to New York a man who had covered himself with $718 worth of airmail stamps.

The mail pilot who is remembered most warmly in Bellefonte is lanky Harold “Slim” Lewis. “He was the which than which there was no whicher,” Jim Kerschner says; “a showman, a hail fellow, a good pilot and well liked.” Considered the ace of the whole bunch, Lewis always seemed to get through, even when other pilots couldn’t.

Slim Lewis stories are part of the town’s aerial lore: Slim diving repeatedly to scatter a herd of bulls owned by a farmer he disliked, Slim buzzing freight trains and unnerving brakemen, Slim punching a hole in a wing by skimming a mountaintop and then complaining because he lost a fountain pen in the process, Slim dropping the Sunday paper to a friend who lived out of town. “Whenever a plane would swoop low over town we just figured it was Slim,” recalls 82-year-old Phil Wion, a former schoolteacher. “We associated him with derring-do.” Lewis survived his airmail career to become a commercial pilot; he died in Wyoming after retiring from the airlines.

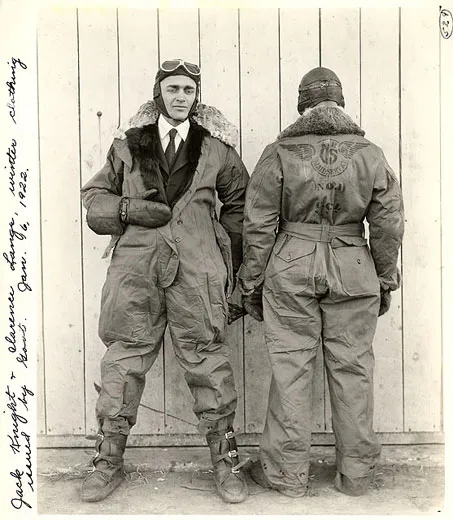

Another favorite was Jack Knight, who became a celebrity when he made an all-night flight from North Platte, Nebraska, to Chicago on an unmarked route in 1921. When he landed in town shortly after getting married, the ground crew dressed a mechanic in a bridal gown and chauffeured Knight and his stand-in bride around Bellefonte in a truck ornamented with bells, shoes, and the tail section of a defunct mail airplane.

Pilot “Wild Bill” Hopson dropped airborne love letters, weighted with bolts, from airfield clerk Charlie Gates to his girlfriend in nearby Hecla Park. Hopson once kept a date in New York by climbing onto the wing of another pilot’s loaded aircraft, snuggling close to the fuselage, and holding onto the guy wires for the chilly two-hour ride.

The aviators were part of the life of the town. They stayed at the Brockerhoff Hotel or boarded with local families, played on local baseball teams, and flew exhibitions for the townfolk. “There was an intimacy between the pilots and the town,” says retired newspaper editor Hugh Manchester, another Bellefonte boy smitten by the romance of flight. “If they spotted a fire they’d buzz the house to make sure people were awake. They were heroes to the kids, girls as well as boys.”

Other aviation luminaries turned up in Bellefonte in the 1920s and early 1930s. Wiley Post and partner Harold Gatry, Amelia Earhart, Eddie Rickenbacker, Will Rogers, Admiral Richard Byrd—all landed their aircraft on the little field at Bellefonte, often forced down by the always-chancy weather over the Allegheny mountain range.

Charles Lindbergh dropped by in the early 1930s. As Manchester recounts the story, the manager of the Bush House hotel took one look at the coveralled flier and concluded that he was a poor risk for the $1.50 room charge. Luckily, somebody recognized the Lone Eagle. Because of the late hour, he had the whole dining room to himself. Lindy showed up again a few years later, and this time a crowd thronged to the field when word spread that he was coming. Spying the mob as he approached the runway, Lindbergh pulled up, sending the disappointed spectators home. Ten minutes later he returned to the empty field and landed. “I think we all followed Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart and the rest a lot more after the airmail came here,” says Sampsell.

Aeronautical prominence was heady stuff for a town whose political and economic muscle, along with its population, had been waning since the 19th century, when Bellefonte produced five Pennsylvania governors. The 1925 move to a larger airfield occasioned a civil celebration. The Kiwanis Club served sandwiches; the Odd Fellows band performed. Phil Wion, wearing his blue serge uniform with the gold stripe, played the trombone. “We were proud because Bellefonte was a main stop,” he recalls. “We played the national anthem and marches. It was a big occasion.”

“We felt like we were part of something,” says Manchester, the unofficial town historian. “When I was 14 I went into an airline building at the 1940 world’s fair in New York and saw an aviation map of the country and there was Bellefonte! We were literally on the map. Oh, there was pride here then. And another big thing, remember a movie called Ceiling Zero with Jimmy Cagney in the 1930s? There’s a scene where a pilot is calling Bellefonte airport: ‘Come in, Bellefonte.’ It’s right in the movie. I suppose the airmail years were like the Golden Age of Greece for us.”

There was, however, a dark side to Bellefonte’s fleeting fame. The long, low ridges that roll across central Pennsylvania like waves on a choppy sea—hard to read from the air, prey to violent weather changes, and short on flat clearings for forced landings—were dreaded by pioneer fliers. Those who endured the area called it the “Hell Stretch.” A 1921 mail pilots’ manual shows what they had to contend with: “On top of the mountain just south of a gap in the Bald Eagle Range at Bellefonte may be seen a clearing with a few trees scattered in it. This identifies the gap from others in the range. The mail field lies just east of town and is marked by a large white circle.”

With aviators forced to navigate by landmarks over mountainous country in rough weather, crashes were inevitable. Between 1918 and 1927, 43 postal pilots were killed. Charles Lamborn, who boarded with the Bellefonte undertaker, died in a crash just a few weeks after regular flights began when his DH-4 somersaulted to earth from 6,000 feet. Field clerk Charlie Gates flew to Cleveland one day in September 1920 with Walter Stevens, another Bellefonte favorite. On landing, Sevens asked Gates if he wanted to go on to Chicago, but Gates had a date in Bellefonte and decided to take the train back. Less than an hour later, Stevens died when the fuel tank on his Junkers Larsen J.L.6 exploded.

Irving Murphy was luckier. When his airplane crashed in flames on Max Sampsell’s father’s farm on the edge of town, “my dad cut him free and rolled him on the ground to put out the fire,” Sampsell remembers. Murphy eventually recovered, thanking the elder Sampsell with a gold watch. And Max Miller, the man who discovered Bellefonte for the airmail service in 1918 and for whom Sampsell was named, died in a fiery crash two years later, the year Sampsell was born.

The disappearance of pilot Charlie Ames in 1925 put Bellefonte on the nation’s front pages. Ames vanished on October 1 en route to Bellefonte from New Jersey on a night when clouds sagged below the Allegheny peaks. Field clerk Gates anxiously checked nearby emergency strips and then stood on the field, listening for an engine that never came. More than a thousand searchers combed the hills east and west of town for the next nine days. Finally Ames’ splintered aircraft and broken body were found near the summit of a mountain a few miles from the Bellefonte field. Longtime residents can still point out the gap in the Allegheny mountains that the courtly, well-liked Ames missed by about 200 feet. Manchester has the cushion from Ames’ cockpit seat with the airplane’s number, 385, on it.

Bellefonte’s last airmail fatality occurred in May 1931, when pilot Jimmy Cleveland died on a mountainside south of town. Forty years later the dead pilot’s brother, accompanied by Jim Kerschner and Hugh Manchester, among others, found remnants of the airplane and had a granite marker placed at the crash site.

When a pilot was killed, someone from the town would escort the body back to the pilot’s hometown, no matter how far away it was. Though saddened by the death of any pilot, the people of Bellefonte understood that the deaths were part of the pioneering process. Indeed, many of the crashes came in the first two years of operation as the Air Mail Service, eager to win Congressional funding, hurriedly trained pilots and set up routes.

Bellefonte’s bittersweet interlude as an airmail stop came to an end in 1933. The official reason was bureaucratic: the federal government ruled that commercial aircraft could not use fields belonging to the Department of Commerce, as Bellefonte’s did because of its radio and weather stations. But the truth was, Bellefonte had become obsolete. Now the mail was carried—along with passengers—on gleaming new long-range commercial transports that had no need to stop in the tiny town. Although Bellefonte continued to operate its radio and weather stations, the refueling service was moved to nearby Kylertown, and even that seldom-used airfield was retired after the introduction of long-range DC-3s.

For nine-year-old Jim Kerschner, life was suddenly drained of excitement. “I went back to the field and there was nothing going on, it was deserted,” he recalls. “Then I went to the strip they moved to at Kylertown, 20 miles west. I wanted to see what it was that took it all away, and there was just this one dinky hangar. I felt terrible.”

The airmail days turned Kerschner and fellow Bellefonte boys Hugh Manchester, Max Sampsell, and Dan Hines into lifelong aviation buffs. Hines, a former mailman who died in 1989, was the most obsessed. He amassed hundreds of photographs, wrote an unpublished manuscript about the airmail, and even sent airmail Christmas cards. “It was all he talked about,” his nephew Robert Hines says. “The airmail was his life. I think it started because his brother Ellis was a mechanic at the field. Dan was forever saying, ‘Did I ever tell you about this or that pilot?’”

Hines and Manchester both learned to fly on the GI bill after World War II, but both let their skills lapse after a few years. “I got a leather jacket, you know,” Manchester recalls, “but then I went to college and then the GI bill expired. I guess I got the Baron von Richthofen out of my system.” Sampsell took pilot training during the war but didn’t get his wings because of a freeze on hiring; he became a B-29 gunner by default. After the war, with a Distinguished Flying Cross to his credit, “I wanted to fly and I didn’t. I thought maybe I’d had enough thrills in the air. So I didn’t follow up, and now I could kick myself.” Kerschner had decided to take flying lessons, but another fatal crash near Bellefonte chilled his desire.

Phil Wion has been on an airplane only twice in his 82 years, but he knows what his hometown lost when the airmail decamped. “We were on the map,” he says. “But now people just look at you when you say you’re from Bellefonte. I tell them it’s near State College. Then I say it’s in the exact center of the state. Then I stop.”

Bellefonte’s original airfield is now hidden by the regional high school and a highway department building; across the street stand a Burger King and a mini-mall. The second field is a patch of farmland across from a lime plant. As Hugh Manchester walks across it, his eyes rise from the silent, empty field to the sky. “This is just about where the big jets start their descent to New York these days,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01.-SI-75-7024~A.jpg)